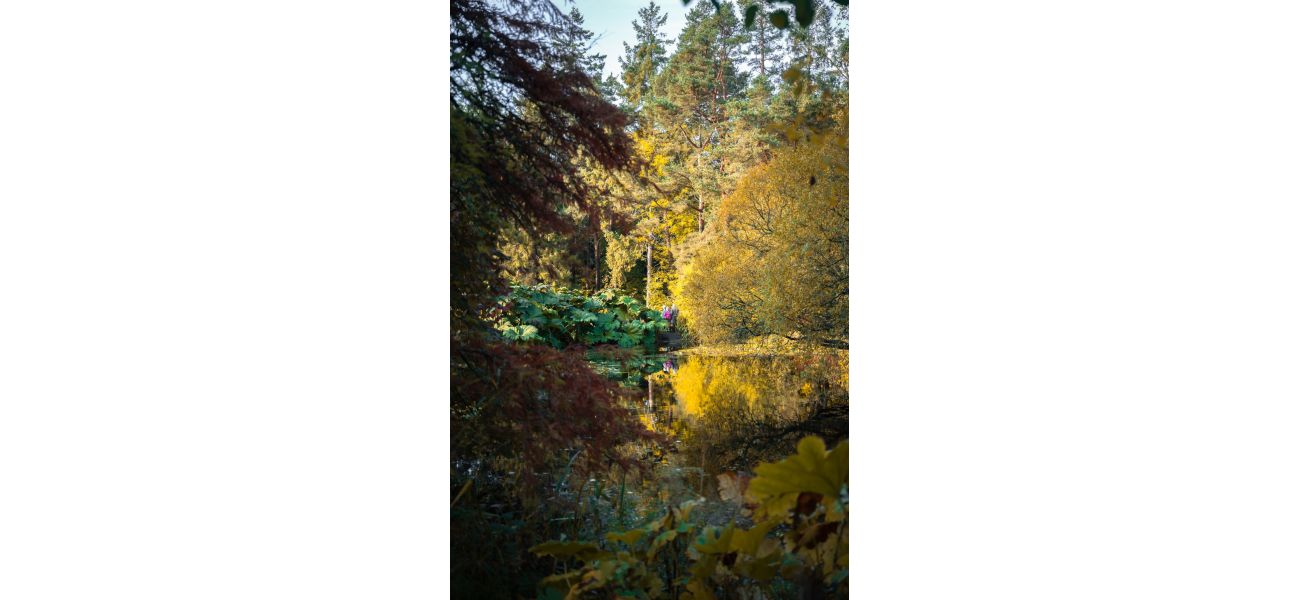

St Andrew Botanic Gardens shows that our biggest issues can be solved by changing our connection with plants.

Harry Watkins, St Andrew Botanic Gardens director, reflects on his childhood surrounded by gardeners, his innovative ideas, and how our understanding of nature is evolving.

November 29th 2024.

As the director of St. Andrew Botanic Gardens, I have always had a deep love for the outdoors. Growing up, my mother was a skilled gardener, and her passion for landscapes greatly influenced my perspective on them. My grandparents were farmers and strong advocates of organic farming, which instilled in us the importance of land stewardship. Even when my grandfather was tending to his carrots, he approached it with a sense of purpose, and I have carried that mentality with me throughout my life. I have always enjoyed spending time in nature, whether it be climbing trees or exploring the woods, and that love has only grown as I pursued a career in landscape architecture.

Now, as a professional in this field, I have specialized in sensitive and heritage landscapes, and many of my clients are botanic gardens, arboreta, and nature reserves. My typical day at work starts at 7am, when I check the key areas of the garden and catch up on any correspondence. After that, I make myself available for any discussions that may arise. The rest of the day is always full of diverse tasks and meetings, as we are currently in a period of significant change and growth. However, I make it a point to balance my time between my colleagues and the important research and development work we are doing. In the afternoons, I leave work early to pick up my daughters from nursery and spend some quality time with them at the park before making them dinner.

This autumn, we have an exciting new project in the works at the gardens. We are replacing overgrown shrubs with a new experiment, covering an area of about 900m2. Our goal is to sow seeds in March and answer the question of how to determine when a plant community has reached maximum diversity. This may seem like a simple question, but it becomes quite complex when dealing with novel ecosystems. To tackle this, we will be using cutting-edge game theory and statistical models, which will provide a unique perspective on this issue over time. Usually, this type of experiment would be conducted in a research plot, but we are doing it right in the middle of the botanic garden, so it must also be aesthetically pleasing in addition to being scientifically sound.

At St. Andrews Botanic Garden, our main objective is to understand how temperate plants are responding to climate change. We are focusing on plants that grow in conditions similar to those found in Scotland and studying the connection between landscape and evolution. In a garden that is designed like a museum, it can be challenging to imagine and study this connection between a plant and its environment. That is why we are turning our attention to the diverse habitats found in Fife, just a short distance from the garden. From sand dunes to rich biodiversity, these areas provide excellent opportunities to study ecology and evolution, and our projects like this one allow us to conduct research that would not be possible in a nature reserve.

As someone who is deeply passionate about conservation and the environment, I believe that every botanic garden has a unique role to play. Some excel at conservation efforts, while others focus on tourism and events. However, the field as a whole is going through a period of change. In the past, botanic gardens were primarily seen as places for students to learn about a wide range of plants. But now, we are making a shift towards a more outward-facing role, involving ourselves in landscape-scale conservation, education for all ages, and offering a fresh perspective on our environment. The challenges that society faces today all have a connection to plants, whether it be food security, water scarcity, or climate change, and botanic gardens around the world are working to contribute to these issues in new and innovative ways.

One of the most critical reasons for this shift in focus is the increasing number of plants at risk of extinction. We are currently facing an unprecedented period of speciation and the movement of plants across regions. This presents one of the most significant and complex challenges for botanists and ecologists today. As plant populations move and evolve, they challenge our previous understanding of nature. We must also consider that every species of plant grows in a range of environments, and with climate change and habitat fragmentation, their survival can be threatened in some areas while they have the potential to thrive in others.

In conclusion, as the director of St. Andrews Botanic Garden, I am continually inspired by the world around us and the ever-evolving relationship between plants and their environments. By embracing new ideas, conducting groundbreaking research, and challenging our previous notions, we can help preserve these essential species for generations to come. The journey ahead may be challenging, but I am confident that the botanic garden sector is well-equipped to face these challenges head-on and make a positive impact on our planet. If you would like to read more about my work and other inspiring stories, I invite you to check out the Life With series and subscribe to Scottish Field for the latest updates.

Now, as a professional in this field, I have specialized in sensitive and heritage landscapes, and many of my clients are botanic gardens, arboreta, and nature reserves. My typical day at work starts at 7am, when I check the key areas of the garden and catch up on any correspondence. After that, I make myself available for any discussions that may arise. The rest of the day is always full of diverse tasks and meetings, as we are currently in a period of significant change and growth. However, I make it a point to balance my time between my colleagues and the important research and development work we are doing. In the afternoons, I leave work early to pick up my daughters from nursery and spend some quality time with them at the park before making them dinner.

This autumn, we have an exciting new project in the works at the gardens. We are replacing overgrown shrubs with a new experiment, covering an area of about 900m2. Our goal is to sow seeds in March and answer the question of how to determine when a plant community has reached maximum diversity. This may seem like a simple question, but it becomes quite complex when dealing with novel ecosystems. To tackle this, we will be using cutting-edge game theory and statistical models, which will provide a unique perspective on this issue over time. Usually, this type of experiment would be conducted in a research plot, but we are doing it right in the middle of the botanic garden, so it must also be aesthetically pleasing in addition to being scientifically sound.

At St. Andrews Botanic Garden, our main objective is to understand how temperate plants are responding to climate change. We are focusing on plants that grow in conditions similar to those found in Scotland and studying the connection between landscape and evolution. In a garden that is designed like a museum, it can be challenging to imagine and study this connection between a plant and its environment. That is why we are turning our attention to the diverse habitats found in Fife, just a short distance from the garden. From sand dunes to rich biodiversity, these areas provide excellent opportunities to study ecology and evolution, and our projects like this one allow us to conduct research that would not be possible in a nature reserve.

As someone who is deeply passionate about conservation and the environment, I believe that every botanic garden has a unique role to play. Some excel at conservation efforts, while others focus on tourism and events. However, the field as a whole is going through a period of change. In the past, botanic gardens were primarily seen as places for students to learn about a wide range of plants. But now, we are making a shift towards a more outward-facing role, involving ourselves in landscape-scale conservation, education for all ages, and offering a fresh perspective on our environment. The challenges that society faces today all have a connection to plants, whether it be food security, water scarcity, or climate change, and botanic gardens around the world are working to contribute to these issues in new and innovative ways.

One of the most critical reasons for this shift in focus is the increasing number of plants at risk of extinction. We are currently facing an unprecedented period of speciation and the movement of plants across regions. This presents one of the most significant and complex challenges for botanists and ecologists today. As plant populations move and evolve, they challenge our previous understanding of nature. We must also consider that every species of plant grows in a range of environments, and with climate change and habitat fragmentation, their survival can be threatened in some areas while they have the potential to thrive in others.

In conclusion, as the director of St. Andrews Botanic Garden, I am continually inspired by the world around us and the ever-evolving relationship between plants and their environments. By embracing new ideas, conducting groundbreaking research, and challenging our previous notions, we can help preserve these essential species for generations to come. The journey ahead may be challenging, but I am confident that the botanic garden sector is well-equipped to face these challenges head-on and make a positive impact on our planet. If you would like to read more about my work and other inspiring stories, I invite you to check out the Life With series and subscribe to Scottish Field for the latest updates.

[This article has been trending online recently and has been generated with AI. Your feed is customized.]

[Generative AI is experimental.]

0

0

Submit Comment