A Prominent Museum Obtained Items From a Massacre of Native Americans in 1895. The Survivors’ Descendants Want Them Back.

A vaccine against tuberculosis has never been closer to reality. But its development slowed after its corporate owner focused on more profitable vaccines.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

The Repatriation Project

A series investigating the return of Native American ancestral remains.

One afternoon earlier this year, Wendell Yellow Bull received a call from a longtime friend with word of a troubling discovery.

Objects from one of the most notorious massacres of Native Americans in U.S. history were in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History, his friend said. Some of them appeared to be children’s toys, including a saddle and a doll shirt.

Memories of what Yellow Bull had been told about the incident throughout his life came rushing back.

Yellow Bull is a descendant of Joseph Horn Cloud, who survived the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee. He recalled being told that members of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment surrounded and killed more than 250 Lakota people, including five of his relatives. And in the days that followed the incident on the Pine Ridge reservation in southwestern South Dakota, people had taken clothing, arrows, moccasins and other objects as trophies.

Word that a New York museum held children’s toys from that day was a tangible reminder of the indiscriminate killing.

“That wasn’t even war, it was just brutal killing,” Yellow Bull, who is a member of the Oglala band of the Lakota and lives on the Pine Ridge reservation, told ProPublica.

On the phone that day, his friend asked if he wanted to try to bring the objects home.

He immediately said yes. Lakota descendants believe mourning over the massacre cannot end until the belongings of those who were killed are returned and spiritual ceremonies are conducted.

“If they are from the killing field, they need to come back,” he recalled telling her.

The objects’ long separation from the tribes whose members were at Wounded Knee underscores a key way in which the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act has failed to bring about the expeditious return of cultural artifacts to Indigenous communities.

While the 1990 law requires federally funded institutions to notify descendant tribes in detail about Native American human remains they hold, its rules and procedures for cultural objects are so lax that tribes often are unaware of what was taken and where it’s held. Museums have taken decades to return human remains, delaying efforts to return cultural items. In addition, the law didn’t provide adequate funding for Indigenous communities to pursue repatriations. These factors have led to decadeslong delays for many tribes to reclaim objects that are rightfully theirs.

NAGPRA “wasn’t crafted to be kind or help us along in our grieving process,” said Alex White Plume, who led the Oglala Lakota tribe’s repatriation efforts in the early 1990s and also has relatives who were killed in the massacre. “It was another attempt to keep us from getting our artifacts that were taken off dead bodies, and not only just at Wounded Knee, but it happened all across the Plains.”

Since NAGPRA’s passage, the AMNH has communicated sporadically with the Oglala Lakota, including sending a notification in November 1993 regarding hundreds of objects in its collections that might be affiliated with the tribe. The vague descriptions of the artifacts made no mention of Wounded Knee.

The museum said in a statement that it provided more detailed information about the Wounded Knee objects in 1997, when a group of Oglala Lakota, who also go by the name Oglala Sioux, met with museum officials and reviewed collections selected by tribal representatives. Other tribes with ties to Wounded Knee, such as the Cheyenne River Sioux, have also met with the museum.

“Periodic consultations with the Oglala Sioux on collections that are of interest to the Tribe have continued since then over various channels,” the statement said. The museum did not provide additional detail about its talks with the Oglala Lakota but said the tribe had not made a request for repatriation, which it described as “multi-year engagements in which museums are guided by the requests and priorities of the relevant tribe.”

Despite the communication between the tribe and the AMNH, the museum has yet to repatriate anything to the Oglala Lakota.

With the passage of NAGPRA, federally funded institutions faced a daunting mandate to document their collections. Some had never conducted a full inventory. And the nation’s oldest museums had, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, built massive encyclopedic collections by funding excavations and expeditions and encouraging soldiers and others to take Native American objects from battlefields.

At the time of NAGPRA’s passage, the AMNH, one of the country’s oldest and largest museums, had approximately 250,000 objects in its North American archaeological collection. It formed an Office of Cultural Resources with a registrar and two additional staff members to do the work. Other staff members also pitched in, according to the museum’s 1992 annual report.

James W. Bradley, a former director of the Andover, Massachusetts, museum now known as the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology, said in a NAGPRA training video: “We basically didn’t know what we had, and we had pretty good catalog control. But intellectual control — knowing what it was, making it available — we really didn’t know.” The law forced the museum “to do what we just had never gotten around to doing, which is to clean up our mess, find out what we had collected, what we had excavated,” he said.

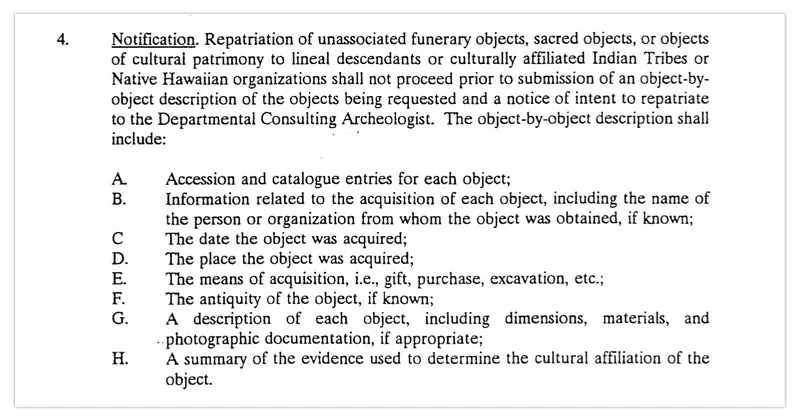

For human remains, the law mandated a detailed accounting, including where they had been excavated and which present-day Indigenous communities might rightfully claim them. Lawmakers had initially wanted a similar item-by-item inventory of cultural items and sacred objects — which could include items like those taken from Wounded Knee, according to Congressional testimony. But such a requirement was seen as too onerous and expensive, so museums’ initial notices about objects sometimes mentioned only who had donated the item. Many would require additional research to decipher.

“When these summaries reached tribal nations, there was not enough information about the origins of the objects, or the way in which the objects were cataloged, or even what the objects specifically were to enable people in those nations to know how to start reclaiming it,” said Margaret Bruchac, a University of Pennsylvania anthropology professor emerita who has worked as a repatriation consultant to museums and tribes.

Bruchac said “tribal nations did not have inside knowledge of museum cataloging systems, and museums did not have sufficient cultural knowledge about tribal materials. So it’s as though they were speaking entirely separate languages.”

The burden of researching the origin of the objects, some of them hundreds of years old, fell to tribal communities, White Plume said. If there’s a record that an object was from the Oglala Lakota, it should be given back without hesitation, he said, “yet they’re sitting there waiting for us to describe in detail the item that we want back.”

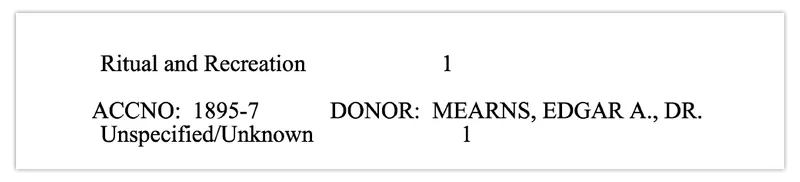

Among the notifications the AMNH sent to the Oglala Lakota was one, dated Nov. 16, 1993, listing hundreds of objects in such broad categories as “dress and adornment,” “ritual and recreation” and “unspecified/unknown.” Among them were the four relics from Wounded Knee.

Despite guidance from the National Park Service, which oversees the NAGPRA program, that museums reveal how they acquired the objects, the AMNH offered only two clues about their origin. In an entry classified as “dress and adornment,” it mentioned “Sioux: Bigfoot’s band” and the donor’s name, Edgar Mearns.

“A Responsibility to Fulfill”As the United States confined tribal nations to reservations, a movement began among Native Americans in 1889 called the Ghost Dance religion. Through dances and ceremonies, some lasting days, they called on their ancestors to help restore their way of life. When it reached the Great Plains — where the government had seized more than 9 million acres of Lakota land — the nonviolent Ghost Dance had the “surrounding country in a state of terror,” according to an 1890 newspaper account.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs considered the Ghost Dance a threat and dispatched the military to enforce a ban on the practice. On Dec. 15, 1890, Indian Police were searching for Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota chief, to question him about his involvement in the Ghost Dance. After encountering him at his home on the Standing Rock Reservation, the officers killed the chief, escalating tensions.

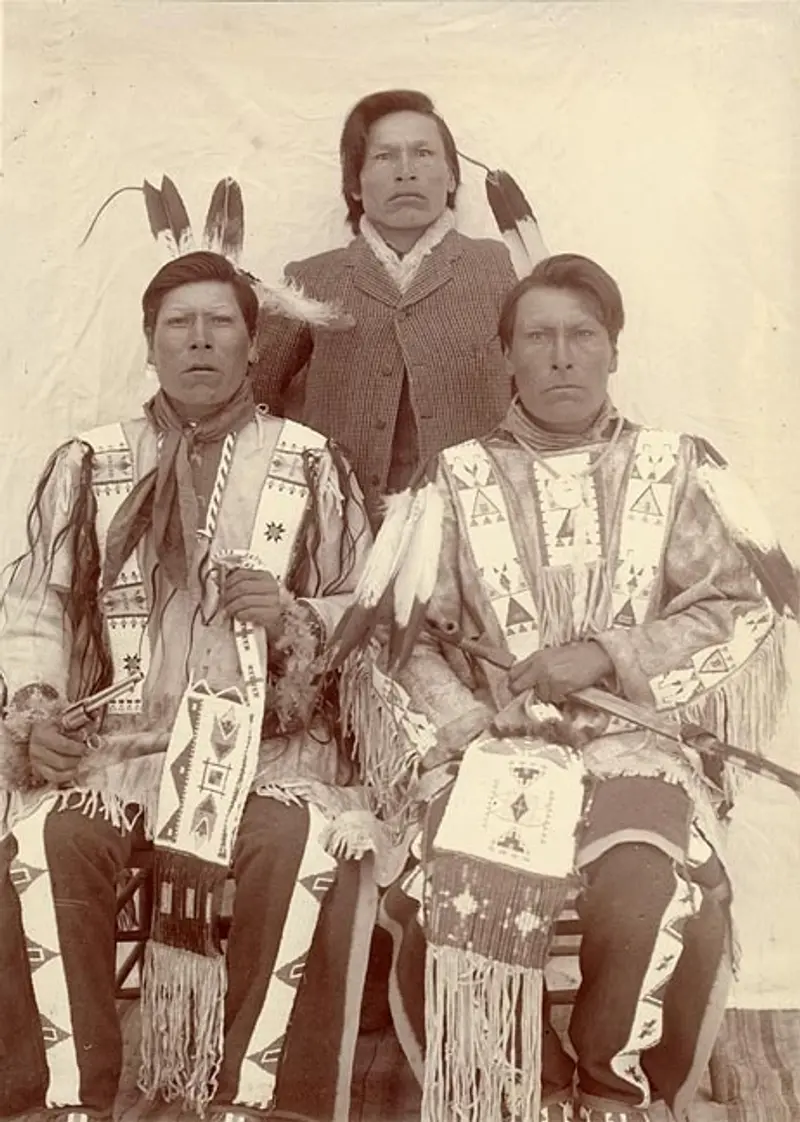

About two weeks later, Mnicoujou Lakota Chief Spotted Elk, who was also known as Big Foot, surrendered with his band to members of the 7th Cavalry. On Dec. 29, soldiers ordered the band of people, who had settled near Wounded Knee Creek, to turn over their weapons. A Lakota man’s weapon discharged, setting off a flurry of gunfire as adults and children ran for cover.

Horn Cloud, Yellow Bull’s great-grandfather, was 16 years old at the time of the massacre and later described what he witnessed to a researcher and writer named Eli Seavey Ricker. Soldiers had surrounded the Lakota when the gunfire erupted. “The shooting was in every direction. Soldiers shot into one another,” Horn Cloud told Ricker. As the Lakota fled, some defending themselves by grabbing weapons they had surrendered. Many sought refuge in a nearby ravine and “some ran up the ravine and to favorable positions for defense,” he told the researcher. When the shooting stopped, Horn Cloud had lost his parents, two brothers and a niece.

An Army captain, whose account was recorded in a Jan. 3, 1891 letter to an Army assistant adjutant general, said he arrived to find fresh wagon tracks and evidence that “a great number of bodies” had been removed from the site. The 8th Infantry buried 146 people in a mass grave, including 82 men and 64 women and children. “The camp and bodies of Indians had been more or less plundered,” the captain wrote.

A soldier named Frank X. Holzner was among those who gathered objects from the killing field, including a toy saddle, a doll shirt, beaver bones, an adornment piece and a bear claw, according to the museum’s handwritten accessions register. The AMNH’s 1895 annual report shows Mearns donated these objects to the museum that year. The museum record doesn’t mention how Mearns had obtained them.

The Army’s initial reports of Wounded Knee described it as a battle. But as more details emerged, including accounts of the killing of women and children as they ran away, the soldiers’ actions were criticized and the commander was investigated. (There have been periodic calls to rescind Medals of Honor awarded to 7th Cavalry troops. And in 1990, Congress apologized for the massacre.)

In the years that followed, Horn Cloud would camp at the site, sleeping on the graves of his lost family members to connect with them, a relative told the National Park Service in a 1990 interview. Horn Cloud and his brother, Dewey Beard, sought compensation from the government for the survivors of Wounded Knee. And Horn Cloud led the effort to erect a stone monument on the site in 1903. The marker lists some of the victims with an inscription, written by Horn Cloud, that says in part: “Many innocent women and children who knew no wrong died here.”

Today, Wounded Knee is marked by a large red sign describing the incident and a small cemetery that was built over the mass grave. The cemetery is surrounded by a chain-link fence that is dotted with prayer offerings — tobacco wrapped in cloth. Last year, the Cheyenne River Sioux and Oglala Lakota tribes purchased 40 acres surrounding Wounded Knee to preserve as a sacred site. A bill before Congress would place the land into a trust status that would prohibit its sale without congressional and tribal approval.

On a recent afternoon, Yellow Bull, wearing a T-shirt reading “Wild Oglalas,” stood near the mass grave and talked about how generations of his family have honored the ancestors who lost their lives there.

Yellow Bull, a Marine veteran, father of six and local county commissioner, is determined to continue preserving the memory of Wounded Knee, he said, including improving the site, protecting it from development and reclaiming the objects that were taken from those who were killed.

“I still have a responsibility to fulfill,” he said.

Cassie Dowdle, a NAGPRA manager for the 900-person Wilton Rancheria tribe, based south of Sacramento, said she has seen inequities in the resources tribes have for pursuing repatriations.

It’s Dowdle’s sole job to contact institutions across the country and use a database to track progress toward repatriation. When she met with representatives at California State University, Sacramento not long ago, she and museum staff sifted through more than 80 bankers boxes to inventory each object. During similar museum visits Dowdle has discovered collections that were never reported to the tribe and pieced together collections that had been separated and housed at various museums.

Wilton Rancheria recently added a staff member to help Dowdle and plans to soon add another. But not all Indigenous communities have such resources. Dowdle, a descendant of the Tule River Yokuts, calls it “unfair.”

“There’s a lot of hurdles, and I’ve seen a lot of tribes, where they ran out of resources,” she said. “They either felt defeated or didn’t have the bandwidth for it.”

The park service provides some grants to fund consultation and repatriation work to improve communication between the institutions and Indigenous communities, including researching museums’ collections. But some tribes don’t have the resources to navigate the grant writing process.

This year, the NPS awarded $3.4 million in grants to museums and tribes, the most since 1994. Even so, grants won’t cover the entire cost of a repatriation, said Rosita Worl, president of Sealaska Heritage Institute and a Tlingit citizen.

She estimates that successful repatriations can run to $100,000 or more. When the tribes represented by Sealaska Heritage have made a claim on an object, they’ve hired a researcher and sometimes sent a group to view it. If there’s a dispute with the institution, the tribe must hire a lawyer, and the costs can quickly increase. Worl said a disagreement over the proposed repatriation of a Teeyhíttaan Clan hat cost her organization $200,000. Ultimately, a full repatriation didn’t occur, and the Alaska State Museum retains partial ownership of the hat. The museum confirmed that a partial repatriation occurred.

“It’s outrageous that the tribes still have to go up against all of this,” she said.

For tribes that can’t afford a dedicated repatriation specialist like Dowdle, it usually falls to a historic preservation officer to navigate the process. Preservation officers are required by federal statute to manage historic properties and preserve cultural traditions. Those responsibilities often keep them “in triage mode,” making it difficult to also take on repatriation work, said Valerie Grussing, executive director of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers.

“There’s an official list of duties as mandated by the National Historic Preservation Act, and repatriation is not one of them,” she said. “They already are having to pick and choose what’s a priority for their community.”

Chip Colwell, a former senior curator for the Denver Museum of Nature & Science who oversaw repatriations, said the funding and power imbalance between museums and tribes was evident in his work. Colwell said his museum’s staff tried to compensate for these inequalities by reaching out to tribes and offering resources and guidance, even when a tribe hadn’t contacted them. The museum’s administration also recognized that the notices they had sent to tribes soon after the passage of NAGPRA were inadequate, and used grant funding to collaborate with tribes on reissuing more detailed summaries of some of those objects. This led to the discovery of things they’d missed.

When the repatriation process fails, it’s frequently because museums are not “taking enough responsibility — moral responsibility — for finding ways forward with tribes,” Colwell said. “And then tribes often just don’t have the resources.”

In the case of objects from a massacre, Colwell wondered why a law is needed for a museum to return them. “I would hope that the American museum, in this case, is just trying to do the right thing,” he said, “and not pretending to be handcuffed by the law.”

There are signs that the AMNH is shifting its mindset. Last week, the museum announced steps toward a “new ethical framework” for its human remains collection, which includes individuals from Native communities. The museum will remove exhibits that include human remains and will devote more resources to reviewing its human remains collection, which includes increasing its “engagements with descendant communities.”

“It Doesn’t Belong to the Museum”The Oglala Lakota don’t have a full-time repatriation specialist or permanent historic preservation officer. The work is instead a team effort by tribal officials and groups of Wounded Knee descendants.

“We don’t have the resources to go out and look for these items, we just hope that somebody tells us about them so we can go do it,” said Justin Pourier, who is coordinating the group’s efforts. Pourier, whose regular job is serving as a liaison between the tribal council and executive committee, is also filling in as historic preservation officer for the Pine Ridge reservation, which is roughly the size of Connecticut.

Pourier said he learned that objects from Wounded Knee were at the AMNH after Erin Thompson, an art crime professor, identified them while researching the museum’s annual reports. She contacted Yellow Bull’s friend, Mia Feroleto, an activist and magazine publisher who recently helped with the repatriation of more than 150 Lakota objects from the Founders Museum in Barre, Massachusetts. It was Feroleto who called Yellow Bull to tell him about the objects.

Yellow Bull, along with a tribal delegation and Feroleto, plans to meet with the museum’s officials to see anything that might be of interest to the Oglala Lakota.

It’s unclear what the tribe would do with the objects if they are returned. Yellow Bull said that decision will be made with other Wounded Knee descendants. But he is certain that the objects at the AMNH belong to and continue to represent the people who were killed, and should be returned so they can be properly mourned.

“It doesn’t belong to you or I, it doesn’t belong to the museum,” he said.