Paramedics are concerned about long ambulance wait times and want the public to be informed.

We often work and reside in the same location as our family members.

May 17th 2024.

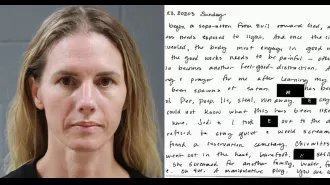

Being an ambulance staff member is not an easy job. It's a constant battle to reach patients in time, and it's taking a toll on their mental and emotional well-being. Glenn Carrington, a paramedic who has been in the field for many years, shares that he often feels guilty, has sleepless nights, and is heartbroken because of his work. He became a paramedic with the noble goal of saving lives, but the reality of long ambulance wait times, overworked staff, and limited resources has made it increasingly difficult to fulfill that goal.

Glenn's shift starts in Peterborough, and he usually has around six or seven call-outs a day. This means covering hundreds of miles, sometimes crossing multiple counties like Hertfordshire, Essex, and London. He recalls one particular job that he can't reveal many details about due to patient confidentiality. However, the memory of being too late to save a life still haunts him. He mentions spending seven long hours with a patient outside the A&E, only to be unable to save them in the end. Another crew had to take over so they could attend to another emergency. The patient, who couldn't have been more than 40 years old, passed away before they could even try to resuscitate them. Glenn vividly remembers that the patient's children were playing downstairs when they arrived, adding to the heartbreaking nature of the situation.

Sadly, this is not an isolated incident. Paramedics all over the country are facing similar experiences of arriving "too late" to save lives. The increasing number of 999 calls has pushed ambulance crews to their breaking point. They operate in large regions and often find themselves stuck outside hospitals for hours, waiting for a bed to become available in the A&E. Bryn Webster, a senior paramedic in Yorkshire, shares that they often witness patients deteriorating in front of them. They do what they can to alleviate their pain, but it's soul-destroying to know that they can't reach them in time. Bryn also adds that some of his colleagues have experienced situations where patients have died in the back of their ambulance.

The pressure and stress of being "too late" on jobs are taking a toll on paramedics across the country. Bryn mentions that many of his colleagues are at their breaking point, especially the younger staff. Unlike before, when people rarely left the ambulance service before retirement, many are now leaving because they find it difficult to cope with the demands of the job.

Through Freedom of Information requests, the situation has been laid bare. In the East Midlands alone, there were nearly 5 million 999 calls between 2018 and 2023, but a significant number of category one call-outs, for life-threatening conditions, were unsuccessful in meeting the seven-minute response target time. In category two call-outs, where the target is 18 minutes for less severe conditions, almost a quarter of the targets were missed. These figures do not come as a surprise to Barbara, a paramedic based in the West Midlands. She shares that they often find themselves racing from one job to another, with delays caused by waiting outside busy A&E departments. She knows that there simply aren't enough ambulances to reach everyone in time.

Barbara also mentions that they rarely have proper meal breaks, often working up to ten hours without any break at all. In the past, they could take a moment to recover after a particularly difficult call-out, but now they have no time for that. She describes ambulance staff as a "strange breed" who just keep going even when faced with immense demands. Mentally, they carry the weight of each job into the next one, with no time to decompress or debrief.

Paul Turner, a paramedic in the North-West, shares the same sentiments. He joined the ambulance service after working in operating theatres and A&E, quickly rising through the ranks to become a paramedic. The job takes a toll on their mental and emotional well-being, but they keep going because they have a duty to help those in need. They may not have the time to take a break and debrief, but they push through because they know that someone else may be in need of their help.

Being an ambulance staff member is not easy. It takes a toll on one's mind and body, causing burnout and emotional distress. This is something that Glenn Carrington knows all too well. As a paramedic, he joined the profession with the noble intention of saving lives. However, the increasing wait times for ambulances, overworked staff, and insufficient resources have made his job more challenging than ever before.

Glenn's shift starts in Peterborough, and on an average day, he receives around six to seven calls. He often covers a distance of hundreds of miles, passing through various counties like Hertfordshire, Essex, and London. There is one particular incident that he remembers vividly, although he cannot disclose many details due to patient confidentiality. He and his partner spent seven long hours with a patient outside the emergency room, only to find out that there were no available beds in the hospital. Another crew had to take over the patient's care so they could attend to another emergency that was 13 miles away.

Glenn recalls the moment when a young lady opened the door and told them that the patient, her husband, was upstairs in the first bedroom on the left. She thought it was just a migraine. But when Glenn went to check on the patient, he found him dead. It was a heartbreaking experience. The patient was not even 40 years old, and his children were playing downstairs when they arrived. Unfortunately, this was not the first time Glenn and his colleagues had encountered such situations.

Sadly, this is a common occurrence for exhausted paramedics across the country. The constant stream of emergency calls has pushed them to their breaking point. Due to the large areas they cover, ambulance crews often have to wait for hours outside hospitals until a bed becomes available in the emergency room. Bryn Webster, a senior paramedic in Yorkshire, shares that they see patients deteriorate in front of their eyes. They joined the ambulance service to help people, but the current situation makes it difficult for them to do their job effectively. They try their best to provide medication like morphine to ease the patient's pain, but it is not enough. It is soul-crushing for them when they see patients die in the back of their ambulance.

Bryn further explains that the tension among paramedics is palpable as they dread starting their shift, not knowing what challenges they will face. They have been in situations where patients and their families have blamed them for taking too long to arrive. The reality is that they are struggling to keep up with the increasing demand, and it is taking a toll on their mental health. The younger staff, in particular, are finding it challenging to cope with these circumstances. In the past, people did not leave the ambulance service until they retired, but now, many are leaving due to the immense pressure and stress.

Through Freedom of Information requests made by Metro, it is evident that the situation is dire. In the East Midlands alone, there were almost five million 999 calls between 2018 and 2023. Shockingly, over 176,000 of these calls were for life-threatening conditions like cardiac arrest, and they were unable to meet the target response time of seven minutes. Even for less severe cases, the response time target of 18 minutes was missed in nearly a quarter of the cases. These numbers do not come as a surprise to Barbara, a paramedic in the West Midlands. She knows firsthand how challenging it is to race from one emergency to another, often delayed due to busy emergency departments. The truth is that there are not enough ambulances to reach everyone in time.

Barbara shares that it is especially difficult when they receive a call for a cardiac arrest or any other life-threatening situation in an area where their family members live. Despite the emotional toll, they have to take a deep breath and continue with their job. She empathizes with the control room staff who have to juggle limited resources and make difficult decisions while they focus on one emergency at a time.

In addition to the physical and emotional strain, paramedics also struggle with long shifts without proper meal breaks. They used to have a few minutes to recover after a distressing call-out, but now, there is no time for that. The demand for their services is high, and they have to keep going, no matter how difficult the job may be. Paul Turner, a paramedic in the North-West, shares that this is a common experience for him as well. He started his career in operating theatres and then moved to the emergency room before joining the ambulance service. He quickly rose through the ranks to become a paramedic, but the job has taken a toll on his mental well-being.

Being an ambulance staff member is not just a job; it is a calling. They are dedicated to saving lives, and they do their best to provide the necessary care to patients. However, the current situation has made it increasingly challenging for them to fulfill their duties. It is time for the authorities to address these issues and provide the necessary resources and support to these heroes who are at the frontlines, battling to save lives.

Glenn's shift starts in Peterborough, and he usually has around six or seven call-outs a day. This means covering hundreds of miles, sometimes crossing multiple counties like Hertfordshire, Essex, and London. He recalls one particular job that he can't reveal many details about due to patient confidentiality. However, the memory of being too late to save a life still haunts him. He mentions spending seven long hours with a patient outside the A&E, only to be unable to save them in the end. Another crew had to take over so they could attend to another emergency. The patient, who couldn't have been more than 40 years old, passed away before they could even try to resuscitate them. Glenn vividly remembers that the patient's children were playing downstairs when they arrived, adding to the heartbreaking nature of the situation.

Sadly, this is not an isolated incident. Paramedics all over the country are facing similar experiences of arriving "too late" to save lives. The increasing number of 999 calls has pushed ambulance crews to their breaking point. They operate in large regions and often find themselves stuck outside hospitals for hours, waiting for a bed to become available in the A&E. Bryn Webster, a senior paramedic in Yorkshire, shares that they often witness patients deteriorating in front of them. They do what they can to alleviate their pain, but it's soul-destroying to know that they can't reach them in time. Bryn also adds that some of his colleagues have experienced situations where patients have died in the back of their ambulance.

The pressure and stress of being "too late" on jobs are taking a toll on paramedics across the country. Bryn mentions that many of his colleagues are at their breaking point, especially the younger staff. Unlike before, when people rarely left the ambulance service before retirement, many are now leaving because they find it difficult to cope with the demands of the job.

Through Freedom of Information requests, the situation has been laid bare. In the East Midlands alone, there were nearly 5 million 999 calls between 2018 and 2023, but a significant number of category one call-outs, for life-threatening conditions, were unsuccessful in meeting the seven-minute response target time. In category two call-outs, where the target is 18 minutes for less severe conditions, almost a quarter of the targets were missed. These figures do not come as a surprise to Barbara, a paramedic based in the West Midlands. She shares that they often find themselves racing from one job to another, with delays caused by waiting outside busy A&E departments. She knows that there simply aren't enough ambulances to reach everyone in time.

Barbara also mentions that they rarely have proper meal breaks, often working up to ten hours without any break at all. In the past, they could take a moment to recover after a particularly difficult call-out, but now they have no time for that. She describes ambulance staff as a "strange breed" who just keep going even when faced with immense demands. Mentally, they carry the weight of each job into the next one, with no time to decompress or debrief.

Paul Turner, a paramedic in the North-West, shares the same sentiments. He joined the ambulance service after working in operating theatres and A&E, quickly rising through the ranks to become a paramedic. The job takes a toll on their mental and emotional well-being, but they keep going because they have a duty to help those in need. They may not have the time to take a break and debrief, but they push through because they know that someone else may be in need of their help.

Being an ambulance staff member is not easy. It takes a toll on one's mind and body, causing burnout and emotional distress. This is something that Glenn Carrington knows all too well. As a paramedic, he joined the profession with the noble intention of saving lives. However, the increasing wait times for ambulances, overworked staff, and insufficient resources have made his job more challenging than ever before.

Glenn's shift starts in Peterborough, and on an average day, he receives around six to seven calls. He often covers a distance of hundreds of miles, passing through various counties like Hertfordshire, Essex, and London. There is one particular incident that he remembers vividly, although he cannot disclose many details due to patient confidentiality. He and his partner spent seven long hours with a patient outside the emergency room, only to find out that there were no available beds in the hospital. Another crew had to take over the patient's care so they could attend to another emergency that was 13 miles away.

Glenn recalls the moment when a young lady opened the door and told them that the patient, her husband, was upstairs in the first bedroom on the left. She thought it was just a migraine. But when Glenn went to check on the patient, he found him dead. It was a heartbreaking experience. The patient was not even 40 years old, and his children were playing downstairs when they arrived. Unfortunately, this was not the first time Glenn and his colleagues had encountered such situations.

Sadly, this is a common occurrence for exhausted paramedics across the country. The constant stream of emergency calls has pushed them to their breaking point. Due to the large areas they cover, ambulance crews often have to wait for hours outside hospitals until a bed becomes available in the emergency room. Bryn Webster, a senior paramedic in Yorkshire, shares that they see patients deteriorate in front of their eyes. They joined the ambulance service to help people, but the current situation makes it difficult for them to do their job effectively. They try their best to provide medication like morphine to ease the patient's pain, but it is not enough. It is soul-crushing for them when they see patients die in the back of their ambulance.

Bryn further explains that the tension among paramedics is palpable as they dread starting their shift, not knowing what challenges they will face. They have been in situations where patients and their families have blamed them for taking too long to arrive. The reality is that they are struggling to keep up with the increasing demand, and it is taking a toll on their mental health. The younger staff, in particular, are finding it challenging to cope with these circumstances. In the past, people did not leave the ambulance service until they retired, but now, many are leaving due to the immense pressure and stress.

Through Freedom of Information requests made by Metro, it is evident that the situation is dire. In the East Midlands alone, there were almost five million 999 calls between 2018 and 2023. Shockingly, over 176,000 of these calls were for life-threatening conditions like cardiac arrest, and they were unable to meet the target response time of seven minutes. Even for less severe cases, the response time target of 18 minutes was missed in nearly a quarter of the cases. These numbers do not come as a surprise to Barbara, a paramedic in the West Midlands. She knows firsthand how challenging it is to race from one emergency to another, often delayed due to busy emergency departments. The truth is that there are not enough ambulances to reach everyone in time.

Barbara shares that it is especially difficult when they receive a call for a cardiac arrest or any other life-threatening situation in an area where their family members live. Despite the emotional toll, they have to take a deep breath and continue with their job. She empathizes with the control room staff who have to juggle limited resources and make difficult decisions while they focus on one emergency at a time.

In addition to the physical and emotional strain, paramedics also struggle with long shifts without proper meal breaks. They used to have a few minutes to recover after a distressing call-out, but now, there is no time for that. The demand for their services is high, and they have to keep going, no matter how difficult the job may be. Paul Turner, a paramedic in the North-West, shares that this is a common experience for him as well. He started his career in operating theatres and then moved to the emergency room before joining the ambulance service. He quickly rose through the ranks to become a paramedic, but the job has taken a toll on his mental well-being.

Being an ambulance staff member is not just a job; it is a calling. They are dedicated to saving lives, and they do their best to provide the necessary care to patients. However, the current situation has made it increasingly challenging for them to fulfill their duties. It is time for the authorities to address these issues and provide the necessary resources and support to these heroes who are at the frontlines, battling to save lives.

[This article has been trending online recently and has been generated with AI. Your feed is customized.]

[Generative AI is experimental.]

0

0

Submit Comment