Beth Healy and Paula Moura of WBUR contributed reporting.

Massachusetts Has a Huge Waitlist for State-Funded Housing. So Why Are 2,300 Units Vacant?

For decades, patients warned Columbia about the behavior of obstetrician Robert Hadden. One even called 911 and had him arrested. Columbia let him keep working.

Deb Libby is running out of time to find a place to live.

Libby, 56, moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, four years ago, in part to be closer to the doctors treating her for pancreatic cancer. She rented an apartment — a converted garage — and spruced it up, patching the walls and repainting all the rooms.

But Libby’s landlord, who has been trying to get her to leave, now wants her out by the end of the month. She can’t find anything else she can afford. Libby earns only a little more than minimum wage working at a hardware store and often has to take unpaid time off when she doesn’t feel well.

She thought she found a potential solution nearly a year ago: She applied for state public housing, a type of subsidized housing that’s almost unique to Massachusetts. But she’s heard nothing since.

“It’s frightening,” she said. “I seriously don’t know what to do. It’s like the system’s broken.”

In a state with some of the country’s most expensive real estate, Libby is among the 184,000 people — including thousands who are homeless, at risk of losing their homes or living in unsafe conditions — on a waitlist for the state’s 41,500 subsidized apartments.

As they wait, a WBUR and ProPublica investigation found that nobody is living in nearly 2,300 state-funded apartments, with most sitting empty for months or years. The state pays local housing authorities to maintain and operate the units whether they’re occupied or not. So the vacant apartments translate into millions of Massachusetts taxpayer dollars wasted due to delays and disorder fostered by state and local mismanagement.

As of the end of July, almost 1,800 of the vacant units, including some with at least three bedrooms, had been empty for more than 60 days. That’s the amount of time the state allows local housing authorities to take to fill a vacancy. About 730 of those have not been rented for at least a year.

The vacancies are aggravating a statewide housing crisis. Massachusetts is spending $45 million a month to house people temporarily at hotels, shelters, college dorms and a military base. Gov. Maura Healey declared a state of emergency in August to deal with the wave of homelessness. Massachusetts reports that the number of families with children staying in emergency shelters has almost doubled in the past year to 6,386.

Our investigation found that one cause of the prolonged vacancies is the flawed online waitlist system the state rolled out four years ago. Massachusetts replaced town-by-town waitlists with a single pool of applicants that 230 local housing agencies draw from. But the state failed to implement an efficient system for selecting potential tenants. Understaffed and underfunded local agencies have to screen applicants for income, criminal background and other eligibility criteria. Apartments are left in limbo as some candidates turn out not to qualify. Applicants often indicate they would accept housing in many towns, but then reject offers from communities that are far away from their current location.

“I think it’s the most horrible, horrible, inefficient program,” said David Hedison, executive director at the housing authority in Chelmsford, a town 30 miles northwest of Boston. He said the agency spent six months contacting 500 people who were on the waitlist for a three-bedroom apartment, before it finally found one who responded and qualified for the unit. “The whole sense of helping residents in your community is gone,” he said.

Since the centralized waitlist went into effect, local housing agencies have increasingly told the state that they need extra time to fill vacancies, requesting more and more waivers to extend the usual 60-day deadline. The number of waiver requests has tripled since 2018, state data shows.

Massachusetts Public Housing Agencies Are Filing More and More Waivers to Keep Units Empty

In 2019, Massachusetts replaced local waitlists with a statewide system. Since then, the number of waivers that local housing authorities have filed because they couldn’t fill a vacancy in the 60-day time limit has more than tripled.

The state’s new secretary of housing, Ed Augustus, acknowledged that there’s no justification for having so many vacancies.

“I think it’s unacceptable,” said Augustus, who was sworn in less than four months ago. “I think that we need to do everything we can to make sure that every single one of our precious public housing units is filled and the amount of time between tenants is as short as is humanly possible.”

Zagaran, a small software developer in Boston, created the program that runs the state’s central waitlist system. Co-founder Josh Zagorsky put the responsibility on state officials, saying that complaints were about “matters of policy, not Zagaran’s software.”

In most states, low-income residents seeking affordable housing must rely on federal housing, vouchers for private housing and other assistance. But Massachusetts is one of four states — alongside New York, Connecticut and Hawaii — with state-funded housing. Massachusetts has more than twice as much state-subsidized housing as the other three states combined.

With tens of thousands of units, Massachusetts public housing is a linchpin of the social safety net for seniors, people with disabilities and families with limited resources. Adding in 31,000 federally funded units, Massachusetts has more public housing per capita than any other state, according to a WBUR analysis. But so many people are in dire need of housing that both the state and federal systems have lengthy waitlists.

The Massachusetts public housing system was originally established to accommodate low-income veterans after World War II. The state typically spends more than $200 million a year on operating expenses and renovations to keep rent affordable for low-income tenants. When units are empty, the local authorities miss out on rental income, but they generally continue to receive the state money.

Massachusetts ranks as the third-most-expensive state for private housing. But tenants in state-funded units typically pay less than a third of their household income in rent. That means a family earning $30,000 per year would pay a maximum of $800 a month for a two-bedroom, far below the state median of about $3,000 a month. And when families in state-funded housing don’t have any income, they only pay the $5 monthly minimum.

But actually landing one of those apartments is extremely difficult. Doris Romero, a housing coordinator at the Women’s Lunch Place day shelter in Boston, has helped dozens of women sign up for state-funded housing. But, she said, only one has actually moved into a state unit in the past year. She was stunned to hear about all the vacant apartments.

“Honestly, that’s a travesty,” Romero said. “The commonwealth should be ashamed.”

Brady Village, a state-funded family housing complex in the western Massachusetts town of Agawam, is a microcosm of a statewide problem. Barbecue grills and children’s bikes stand outside some of the units where families live. But Agawam Housing Authority Executive Director Maureen Cayer points out one vacancy after another. Ten of the 44 units were empty in July, including seven that had been unoccupied for more than a year.

“They’re clean. They’re bright. And they’re empty,” said Cayer, who is responsible for overseeing the buildings and filling the vacancies. “It’s not the way it’s supposed to be.”

Cayer blames the statewide waitlist for the vacancies in Brady Village. Historically, local agencies with state-funded housing each managed their own small waitlists for homes. But critics complained that some local housing authorities played favorites, and that the process was cumbersome for prospective tenants, who had to file separate applications, often in person, for every community where they were interested in living.

To address the concerns, the Legislature ordered the state in 2014 to create a statewide online system, called the Common Housing Application for Massachusetts Programs, or CHAMP. The system was supposed to make it easier for people to find housing by allowing them to apply anywhere in the state with a single form. Each housing agency receives a state-generated list of people who indicated an interest in that area.

The system, which has cost the state $6.8 million, ran into problems as soon as local housing authorities began using it internally in the fall of 2018. In January 2019, a state housing official sent a memo to all local agencies alerting them that they might need additional staff to screen applicants. The memo said that the new system created an “acute administrative challenge” to determining who qualifies for priority placements. The state gives priority to people whom it considers homeless through no fault of their own, due to reasons like a natural disaster or domestic violence. As a practical matter, it’s almost impossible for families to obtain state housing without priority status.

When the new system launched for the public that April, more than three years behind schedule, housing authorities immediately complained it made it harder to sift through the flood of applications and find tenants who qualified for the units. “The system is not working,” the housing authority in Warren, a town in central Massachusetts, told the state in November 2019.

Despite these shortcomings, Massachusetts officials hailed the new statewide waitlist as a success. At a formal celebration at the Statehouse in December 2019, complete with a reception and appetizers in the marbled Great Hall, then-Gov. Charlie Baker honored the development team with an award for “excellence in public service.”

In the four years since, complaints from local housing officials have only grown louder. Under the old system, it would take the Agawam Housing Authority a couple months to find a new tenant, Cayer said. Now, it takes years. Baker did not respond to a request for comment.

The first problem is that the application is lengthy and complicated. Agawam’s old form was eight pages long. The new statewide form is 26 pages. There is no initial screening or check to see if applicants have the paperwork they need, so housing agencies generally can’t identify problems until late in the process — when an apartment is available and someone’s name comes to the top of the list.

Cayer recalls a two-bedroom unit in Brady Village that was empty for two and a half years before finally getting a tenant this past February. Agawam housing officials went through roughly 600 names, grabbing a batch from the waitlist almost every week and mailing out letters with a 15-page supplemental form to determine eligibility. Applicants had 10 business days to reply.

Most never responded. Or it turned out they weren’t eligible for public housing. Or they had to be moved down the list because they didn’t qualify for priority status as they contended they did. Or, when they were finally offered a home, they turned it down because they had competing offers or they decided Agawam was too far away from their work or family. The typical applicant seeks housing in 20 communities, according to the state.

“It’s an exercise in futility,” Cayer said. “We have people calling or applying from the Cape or from Boston. They can’t reasonably live here.” (The largest town on Cape Cod, Barnstable, is 150 miles from Agawam.)

The state revamped the applicant form in December, adding a map of the 14 counties in Massachusetts in hopes of dissuading people from signing up for housing in communities they have no intention of living in. So far, Cayer said, the map has not been effective in deterring far-flung people from applying to Agawam.

And since people often apply to multiple towns, it’s common for them to be contacted by many housing authorities at once. As a result, multiple agencies simultaneously hold units open for the same applicant, who can choose only one place. Meanwhile, Cayer said, some waitlisted families are stuck in shelters or sleeping in their cars.

“I think it’s criminal,” Cayer said. “Criminal.”

Public records show that local housing authorities have regularly told the state they need more time to fill vacancies because of problems with the CHAMP waitlist, as well as a lack of staff to comb through applications.

The state has received so many complaints about the CHAMP system that it has hired a Boston marketing firm, Archipelago Strategies Group, to take over some of the screening of public housing applicants, starting this month. Archipelago referred questions to state officials.

A state housing official said Archipelago will be paid $3.3 million to go through the backlog of applicants requesting priority status for housing assistance. But local housing authorities will still be responsible for some of the vetting, such as background checks. The secretary of housing said he expects improvements soon but doesn’t know when the problems will be fully resolved.

“This is an iterative process,” Augustus said. “We’ll continue to make changes as necessary.”

The state also significantly reduced the size of the waitlist for state-funded public housing this spring — but not by placing people in apartments. Instead, it dropped tens of thousands of people who did not respond to a letter in the mail asking them to confirm that they were still interested in housing.

The waitlist is a mystery to people who are desperate for housing. They don’t know where they stand in the line of applicants or when they will find an apartment.

After applying for state-subsidized housing in January, Konstantinia Gountana, 41, of Arlington, and her family are living with these unknowns.

During the pandemic, Gountana’s husband lost his job as a barber in Harvard Square and three of her family members died, including her only relative in Massachusetts.

“Anything that could go wrong went wrong,” she said. “It was a disaster.”

To make ends meet, she and her husband started to drive for Uber on alternating shifts, with Gountana looking after their infant and 5-year-old during the day, and her husband handling child care in the evening. But their Toyota Prius broke down and they had to quit.

The Gountanas are facing steep odds. They limited their application to one town: Arlington, where more than 25,000 families are on the waitlist. They didn’t want to uproot their older son, who has symptoms of autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. His therapist had recommended against changing his school and schedule. The family also applied for housing vouchers, but there’s a long wait for those, too.

The Gountanas were evicted in June. They were forced to toss most of their belongings and squeeze into a friend’s spare room with their two kids. But they aren’t sure how long they can stay.

“Everything got destroyed,” Gountana said, bouncing her now 21-month-old son on her knee to keep him quiet. “I’m embarrassed. I’m sad. All these feelings.”

The executive director of the Arlington Housing Authority, Jack Nagle, said that filling vacancies is a challenge because of the state’s online waitlist system. Twenty of Arlington’s 700 state-funded units sat empty as of the end of July.

Gountana is still hoping to move into a state-funded apartment. “Honestly, I did not expect it to be so, so long,” she said.

The waitlist woes are one of several reasons for the glut of vacancies. Hundreds of apartments across Massachusetts can’t be filled because they’re undergoing renovation, or because local housing authorities lack the staff or funding for vital repairs.

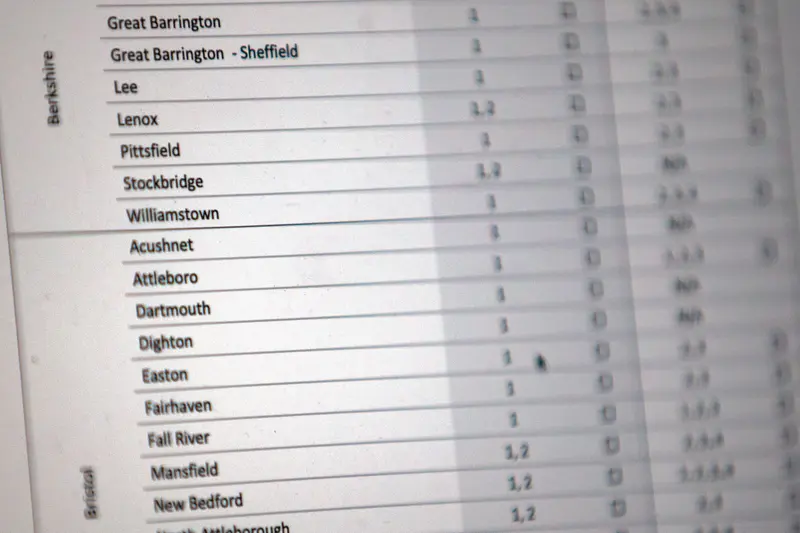

Why State Public Housing Units Sit Vacant in Massachusetts

Local housing authorities submit a waiver and an explanation to the state if they expect that a unit will need to be vacant for longer than 60 days. For apartments that were vacant as of July 31, 2023, the following reasons were given.

Units in the town of Adams, in the Berkshires near the New York state border, have been condemned as the problems piled up. And housing officials have razed other dilapidated apartments in cities such as Lowell, northwest of Boston, and Fall River, near the Rhode Island line. About 70 apartments across Massachusetts have been demolished or sold in the last dozen years, according to the state housing agency.

“We need a long-term plan,” said Rachel Heller, of the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association. “We can’t lose these homes.”

For decades, advocates have warned that the state public housing system needs billions of dollars in funding for additional staff and renovations, including new roofs, plumbing and heating systems. A 2006 audit called the situation a “state of emergency.”

But those alarms weren’t heeded. In 2018, the Legislature allocated $600 million over five years for capital expenditures for public housing — not enough to catch up with all needed repairs. Today, local authorities have a $3.2 billion backlog for renovations, by the state’s estimate. Augustus, the state housing secretary, said the state is working on a new bond bill, but it was too early to provide details.

Advocates pushed for $184 million this year for operating and maintaining the units day to day, but Healey’s proposed budget allowed for only half that amount.The Legislature ultimately allocated$107 million, an increase of 16% from last year. Healey, House Speaker Ron Mariano and Senate President Karen Spilka declined to be interviewed.

In the meantime, the state public housing stock is suffering. Take the housing authority in Watertown, a Boston suburb, which has six maintenance workers. Patrick Breen, the maintenance supervisor, said that’s not enough to care for the agency’s 589 units, many of which were built 60 to 70 years ago.

Breen said his crew must focus on emergencies, like broken cast-iron pipes and electrical outages. Often, no one is available to prep empty units for new families. Some longtime tenants just abandon the apartments, forcing the maintenance crew to haul out their belongings and repair walls, floors and counters. The units sit for months before they are ready to lease.

“It’s a nightmare,” Breen said. “There’s not much more you can do really, when you don’t have enough staff.”

Some apartments across the state stay in limbo even longer while housing authorities plan major renovations or redevelopment projects. That’s what happened in the city of Somerville, where units in the Clarendon Hill complex sat empty for as long as six and a half years before work began in March on a new $200 million private development of affordable and market-rate housing at the site. During that time, the state continued to pay Somerville to manage the vacant units.

Somerville Housing Authority interim director Joe Macaluso explained that the agency hadn’t wanted to spend money maintaining aging buildings that it planned to demolish, even though they were still livable. “We would have had to inject capital — good money after bad money — just to get them ready,” he said.

The state’s executive housing office rarely questions these long vacancies, approving 92% of requests to keep units empty past the 60-day deadline. But advocates for homeless people say they wish agencies would let someone live in the empty apartments — even if it’s only temporary.

“If you were to ask me or ask our clients, they would say, that’s four or five years I’m not in a shelter or out in the street,” said Mike Libby, executive director of the Somerville Homeless Coalition. He’s not related to Deb Libby, who’s seeking housing.

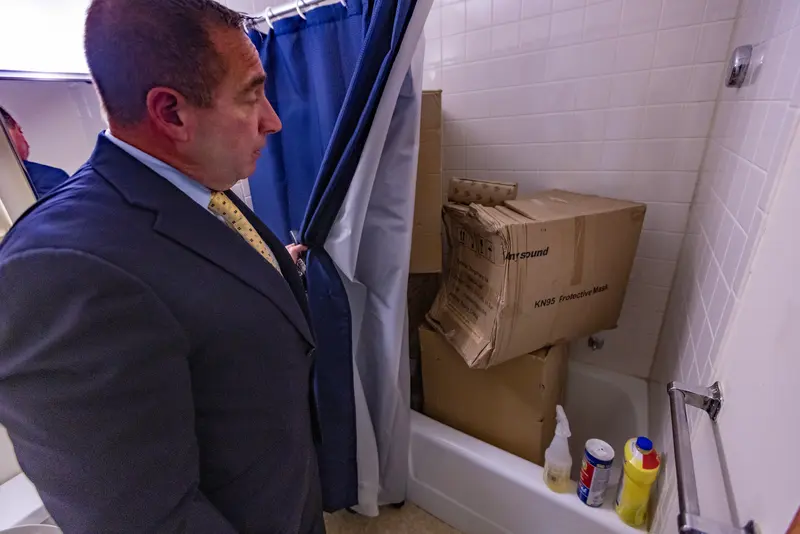

Across the state, housing authorities have also converted at least 121 state-subsidized apartments for uses including office spaces, storage areas and laundry rooms — further shrinking the pool of units available for families and seniors.

The Boston Housing Authority converted 11 units to offices for employees and tenant organizations and set aside another for a children’s program. Nearby, the Somerville Housing Authority repurposed 10 apartments, including a two-bedroom unit that was turned into office space for the agency’s police department.

Beverly, Fall River and Quincy turned units into laundry rooms. And the housing authority in Salem took four apartments in a downtown tower for seniors and converted them into offices, including a break room and space for file storage. After the president of the tenants’ association stumbled onto two of the repurposed units last year in the building he lives in, the housing authority launched eviction proceedings against him. The agency said he was trespassing. He said there was no indication that the offices were off limits. The case is pending.

One social services executive was astonished to hear about all the apartments converted to offices and storage.

Housing “seems like a bigger priority than a break room or storage facility,” said Laura Meisenhelter, executive director of North Shore Community Action Programs, which runs a family shelter. “You know, you can get sheds at Home Depot.”

Augustus, the state housing secretary, said there are often good reasons to repurpose units, such as to provide a library or a laundry room in a complex for seniors. He said the state has to sign off on the conversions, but it generally defers to local officials. “There’s always going to be unique circumstances,” Augustus said.

At least one agency hopes to switch its converted units back soon. The Fitchburg Housing Authority plans to build a $12 million community center with plenty of office space, enabling it to convert seven offices back to their original purpose: housing.

Deb Libby, the Worcester woman facing eviction at the end of the month, never worried about becoming homeless. She’s worked at Lowe’s for two years, doing everything from fielding questions to moving supplies in the garden section. But it’s been harder to work a full schedule since she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer five years ago. Her job is physically demanding — she walks six to eight miles a day — and the disease has weakened her immune system, forcing her to take frequent days off without pay.

She said surgery removed the cancerous tissue in November 2018 and after that she’d been in remission. But an MRI recently found the cancer has spread to the liver. “We’re still trying to figure out what to do with that.”

Libby has struggled to keep up with the $1,450 monthly rent for her one-bedroom apartment near the College of the Holy Cross.

For a while, pandemic relief funds helped her pay the rent. Then a friend pitched in. But the building was sold, and she didn’t have a long-term lease.

Last October, after her landlord began the formal eviction process, Libby signed up for state public housing in Worcester. Libby managed to stave off the eviction in housing court for a year with help from an attorney from a legal aid nonprofit. As part of an agreement to settle the case, the landlord acknowledged Libby was not at fault, promised to provide a good recommendation, and cited “economic reasons” for the eviction. The building’s owner did not respond to an email asking for more specificity.

Libby prefers to remain in central Massachusetts, close to her mother, three children and three grandchildren. Her family doesn’t have room for her, she said, and she’s willing to move anywhere in the state to find an affordable apartment. Early this year, she expanded her search for public housing to 30 additional communities — from Chicopee in western Massachusetts to Provincetown on the tip of Cape Cod.

In June, she applied for priority status for state housing on the grounds that she is losing her housing through no fault of her own. But Libby said she hasn’t received any response. When she called some housing authorities, she said, they wouldn’t tell her where she stands on the waitlist.

“I just really need something,” she said. “I really need help.”

Libby said she has no idea where she will live — maybe in her truck or a friend’s garage. She was surprised to hear about all the units sitting vacant across the state.

“It’s frustrating,” she said. “It’s maddening.”

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

Beth Healy and Paula Moura of WBUR contributed reporting.

Beth Healy and Paula Moura of WBUR contributed reporting.