This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with High Country News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Washington State Is Leaving Tribal Cultural Resources at the Mercy of Solar Developers

The state’s program for reclaiming abandoned coal mines has long been plagued with problems, but state and federal officials have done little to prepare for this reckoning.

In the autumn of 2021, an 800-page report crossed the desk of Washington state lands archaeologist Sara Palmer. It came from an energy developer called Avangrid Renewables, which was proposing to build a solar facility partly on a parcel of public land managed by the state. Palmer was in charge of reviewing reports like these, which are based on land surveys intended to identify archaeologically and culturally significant resources.

Developers have proposed dozens of similar solar and wind projects across the state — a “green rush” of sorts amid rising fears of climate change. With the projects came more reports.

Often, Palmer, who worked for the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, read the reports and signed off; sometimes she shared notes on any concerns or told the developer to have the archaeologists they’d contracted with do additional fieldwork. This time, as she looked at the report, she grew concerned. The consulting company that Avangrid had hired, Tetra Tech, had included a lot of boilerplate language about human history on the Columbia Plateau, but fewer details than Palmer expected about what was actually found on the land.

Palmer knew that the parcel, located on a ridge called Badger Mountain, near the confluence of the Wenatchee and Columbia rivers, was historically a high-traffic corridor for the škwáxčənəxʷ and šnp̍əšqʷáw̉šəxʷ peoples (also known as the Moses Columbia and Wenatchi tribes). The area would likely be rich in cultural resources, including historic stone structures and first foods, the ingredients that make up traditional Indigenous diets.

Palmer was used to helping developers improve their technical reports to meet state standards. So, as soon as the snow melted, she drove out to Badger Mountain to look at the land herself.

As she walked the sagebrush overlook, Palmer quickly found signs of current-day Indigenous ceremonial activity, as well as ancient sites such as stone structures that can look like natural formations to the untrained eye but serve a variety of functions, including hunting and storage.

Most of the proposed development is on private lands, which Palmer lacked the authority to access. But in about 20 hours of fieldwork on the state-owned parcel, over the course of several days, Palmer said she found at least 17 sites of probable archaeological or cultural importance not listed in Tetra Tech’s survey. She would find more on subsequent visits.

Over the next year, Palmer’s findings — and how she shared them — would pit her against corporate and political forces that seemed determined to push the project through.

As soon as she returned from her initial trip, Palmer emailed her findings of “serious deficiencies” in Avangrid’s report to her colleagues at the Department of Natural Resources, which manages lands like the Badger Mountain parcel for the purpose of generating revenue for public services. Palmer called the situation “extraordinary,” noting that she had found a significant network of interconnected archaeological sites from before the arrival of white settlers.

Palmer also forwarded her findings to two tribal nations whose resources would be impacted: the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, where the škwáxčənəxʷ and šnp̍əšqʷáw̉šəxʷ people are enrolled today. The tribal nations retain the right, via treaty and other legal mechanisms, to continue cultural practices like harvesting on any public lands in their ancestral territory. Treaties are considered the “supreme Law of the Land,” according to the U.S. Constitution, and the courts are supposed to view them as “equivalent to an act of the legislature,” according to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall.

States play a role in upholding treaties, which require them to protect cultural resources on public lands. To do that, the state needs to know what resources are out there. For energy projects in Washington, state officials like Palmer generally rely on developers to conduct the surveys to find out.

Developer-conducted surveys have caused issues elsewhere: Officials in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, for example, pressured their consulting archaeologists to change a report that concluded a Black cemetery was eligible for historical designation, while in Louisiana, an archaeological firm, under pressure from its clients, edited a report to downplay evidence that a grain facility threatened notable Black historic sites.

Joe Sexton, an Indigenous rights attorney with the Washington law firm Galanda Broadman, said developer-funded archaeologists are a chronic problem in the state. Their reviews “are at best deficient and at worst deliberately negligent in overlooking tribal interests, overlooking clear potential for, for example, human burials, not considering sacred sites, not discussing with tribal elders and considering oral histories in particular,” he said.

Tetra Tech did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In an emailed statement, an Avangrid spokesperson said the company has followed “all relevant law and regulation” with regard to the Badger Mountain solar project. The company “has taken additional steps to accommodate stakeholder feedback where possible,” the spokesperson wrote. “We will continue to do so as the project moves forward.”

In late May and early July of 2023, the Colville Tribes and the Yakama Nation officially registered their disapproval of the survey for Badger Mountain with the state agency in charge of permitting the solar project. Last fall, the agency took the rare step of requiring Avangrid to pay for a second, independent survey.

But even a perfect cultural survey only tells the state where cultural resources are; it doesn’t necessarily prevent them from being damaged, removed or destroyed.

In June, at a tribal summit with state agencies and developers in Tacoma, Washington, Yakama Nation archaeologist Noah Oliver criticized the state’s green rush. “It’s a land grab,” he said, pointing to the entire method of siting, permitting and consultation for renewable energy projects. “The system we work under is broken.”

The Yakama Nation considers all of Badger Mountain to be a traditional cultural property — government parlance for a place the tribes have identified as significant and eligible for federal protections. It is also an important harvesting site for the heirloom foods that make up much of Colville people’s diets. Andy Joseph Jr., an elected member of the Colville Tribal Business Council, estimated that the Badger Mountain project would destroy roughly half the root vegetable harvest in the area.

Joseph said the destruction of tribal food systems began when white settlers arrived, eroding community health and forcing assimilation. The building of Columbia Basin hydroelectric dams in the mid-20th century extirpated salmon from much of the upper Columbia River. The impacts were so severe that the Yakama Nation called the construction of one dam “cultural genocide,” committed to develop renewable energy, and Joseph said the new development plans continue that practice.

Joseph, who has also served on the National Indian Health Board, said protecting the healthy foods on Badger Mountain is vital to the well-being of Native people, who experience some of the nation’s worst health disparities. Tribal leaders have declined to describe or identify their heirloom crops out of concern that the non-Native public might overharvest or commercially exploit them.

“This is one of the last places where our roots aren’t being sprayed by anybody or they’re not grazed over by animals,” Joseph said. “It’s our food cache, and we don’t want it ruined.”

This is one of the last places where our roots aren’t being sprayed by anybody or they’re not grazed over by animals. It’s our food cache, and we don’t want it ruined.

As well as being a source for foods, Badger Mountain is culturally critical as an active ceremonial ground, and some of the rock features crafted by tribal ancestors are spiritual in nature. As they do with root vegetables, the tribal nations keep ceremonial information private to protect it from appropriation or commodification by non-Natives. But Joseph said root harvesting begins with a prayer ceremony, which tribal elders teach to the youth, feeding both the body and spirit.

Political pressure to advance the Badger Mountain project has been growing for years. In 2018, DNR developed a plan to lease out state lands for solar and wind projects. Three years later, Gov. Jay Inslee signed his blockbuster Climate Commitment Act, formalizing a statewide goal of reducing net climate pollution to zero by 2050 and opening the doors to a sweeping array of development opportunities. As of early 2023, developers had proposed 50 new solar and 12 new wind projects across the state, according to government data. Most are in eastern Washington where the ancestral lands of the Colville Tribes and the Yakama Nation are.

By March 2019, DNR was discussing developing Badger Mountain with Avangrid, which had become a powerful player in the Northwest’s push for green energy. The company built Washington’s largest solar facility, the Lund Hill solar project, south of Badger Mountain in Klickitat County, and it also operates the largest solar facility in Oregon.

Avangrid, its subsidiaries and its parent company, Iberdrola, have faced legal and economic tumult in recent years, including millions of dollars in fines related to service issues with its subsidiary Central Maine Power and opposition to a now-canceled merger agreement with New Mexico’s public utility. In a statement, a company spokesperson said that Central Maine Power had improved its standing and “met or exceeded service quality benchmarks for more than three consecutive years.” Concerns regarding the merger were not relevant to Badger Mountain, the statement reads, and the merger “had wide support.” The company is “dedicated to being a socially responsible business and corporate citizen,” the spokesperson said.

In Washington, as Avangrid was in talks with DNR about Badger Mountain, the company was also negotiating leases for private lands around the state’s parcel and was ready to move ahead.

Before Avangrid could build, however, it would have to satisfy the State Environmental Policy Act, in part by documenting potential cultural resources. That’s where the developer-conducted surveys come in.

To conduct its survey of Badger Mountain, Avangrid hired Tetra Tech, a Pasadena-based company that has previously faced criticism for insufficient scientific work. In 2018, two Tetra Tech supervisors pleaded guilty to falsifying records on a shipyard cleanup project in San Francisco, part of an ongoing legal battle over the allegedly inadequate cleanup of a Superfund site. The U.S. Department of Justice joined three whistleblower lawsuits against Tetra Tech. In response, Tetra Tech sued the companies that the Navy hired to look into the cleanup work. Last year, a group of homeowners sought class status against Tetra Tech, alleging the company had falsified work that stunted property values; Tetra Tech challenged a separate class action lawsuit about the same site, filing a motion to dismiss and arguing the case was based on “unsupported speculation about alleged widespread data falsification.”

Given the issues she found with the survey, Palmer said, “it always seemed like the simplest thing to do would have been to tell Avangrid, ‘Look, we're going to need you to hire a different consultant.’”

But the Department of Natural Resources didn’t do that.

Critics say DNR’s dual responsibility for both protecting and monetizing state lands has sometimes worked against the interests of tribal nations. “We've seen prioritization of monetary interest, certainly over tribal resources and resources important to Indigenous people,” said Sexton, who has represented the Yakama Nation against city and county governments, as well as federal agencies, to protect tribal rights on treaty lands.

DNR “is committed to engaging Washington’s Tribes when it comes to safeguarding lands and resources,” agency spokesperson Courtney James wrote in an emailed statement. “While we are committed to using state lands to build the clean energy future we need, we understand the care we must take to ensure projects don’t impact critical cultural resources.”

In an interview, Michael Kearney, head of product sales and leasing at DNR, said, “I do understand the concerns with the project proponent hiring their own specialists,” adding that “there are potential pitfalls with that.” But he said the agency doesn’t regulate renewable energy developers and can’t force developers to edit their cultural survey reports.

“We generally consider that to be a proprietary or business relationship,” Kearney told High Country News and ProPublica. “We’re not really playing that regulatory function.”

Palmer, however, felt compelled to step in.

After conducting her field work, Palmer emailed her colleagues: “I consider it unlikely that Tetra Tech will be able to produce a legally defensible technical document.”

Palmer said her findings quickly escalated tensions. “What I had seen was very inconvenient to the development plans out there, and it was clearly something that the project proponents did not like,” Palmer told HCN and ProPublica. She believed that it put DNR leadership in a “very uncomfortable situation where they had an unhappy, politically connected developer.” Neither Avangrid nor DNR would comment on this characterization.

Avangrid itself pushed back.

On May 5, 2022, about two weeks after Palmer emailed her findings to DNR colleagues, Avangrid’s director of business development, Brian Walsh, sent her a string of urgent text messages, which HCN and ProPublica obtained through a public records request. After Palmer said she wasn’t available to talk, Walsh insisted that she keep her findings private and not share them with the tribes.

“I wanted to make sure any comments or concerns based on your field visit to Badger Mtn remain internal until we have had a time to discuss w peer professionals,” Walsh wrote. “We would like the opportunity to discuss any of your concerns before they are communicated externally, especially w the tribes.”

In fact, Palmer was at Badger Mountain that day — showing her findings to a Colville tribal archaeologist. DNR shares cultural surveys with the tribes, and Palmer regularly communicated with tribal archaeologists.

“Can you respond to my question on any external communications that you have made on Badger cultural?” Walsh persisted. “Specifically the tribes.” Palmer did not respond.

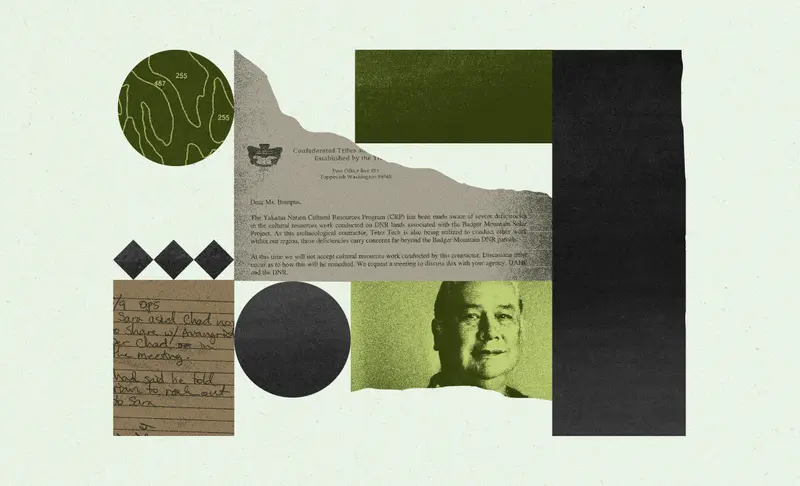

On May 12, 2022, after Palmer told the Yakama Nation about her findings on Badger Mountain, tribal leaders sent a letter to the state, saying the deficiencies in Tetra Tech’s report had far-reaching implications, since the company was doing other work on Yakama lands as well. “At this time we will not accept cultural resources work conducted by this contractor,” wrote Casey Barney, manager of Yakama Nation’s cultural resources program.

In response, DNR held a series of meetings with other agencies, Avangrid and tribal representatives. Handwritten DNR meeting notes obtained through a public records request show that Walsh told DNR officials that Palmer had gone “rogue.” DNR confirmed that this was Walsh’s characterization of Palmer.

According to Palmer, DNR leadership stopped including her in meetings with Avangrid and appointed the agency’s clean energy program manager, Dever Haffner-Ratliffe, as the sole point of communication with Walsh.

Agency group chats show that Tetra Tech instructed its staff not to speak with Palmer, even regarding other projects, for “political” reasons.

We would like the opportunity to discuss any of your concerns before they are communicated externally, especially w the tribes.

Emails from June 10, 2022, show that Walsh asked for the power to vet external agency communications before they went out to the tribes or other agencies and threatened to pull Avangrid’s business — by moving the project forward on private lands only, depriving the state of any potential revenues — if the agency didn’t comply. He also asked DNR to issue Avangrid a lease before the state’s environmental review process was complete; DNR and Walsh acknowledged this was something the agency had done for him before under other circumstances. Haffner-Ratliffe told Walsh that neither would be possible.

But DNR had been sending Walsh mixed signals. Before his exchanges with Haffner-Ratliffe, the agency had already given Avangrid a letter of intent to lease once the review process was complete, for Walsh to show to his superiors. And the agency had allowed Walsh to vet a draft of the letter before sending it out.

Emails show that DNR intended the letter to assure Avangrid that Walsh was making progress securing the land, even while the environmental review process was pending. And the agency knew it had to be careful, because the letter could give the impression externally that it had made the decision to lease before the environmental review was complete.

Even after Haffner-Ratliffe denied Walsh’s requests for a lease and approval to vet communications, he kept pushing. He kept repeating these requests and asked her to cite state laws supporting her denial of them; he also asked her to loop in a supervisor who could authorize her reply.

By the end of the year, another state lands archaeologist besides Palmer had emailed Haffner-Ratliffe regarding Walsh’s behavior in meetings, saying he had been “combative and provocative to me in particular,” and tried to “bully me into giving him the answers he wanted.” The interactions, she wrote, left her shaking and in a cold sweat.

On Dec. 21, 2022, Haffner-Ratliffe emailed DNR leadership asking them to address Walsh’s behavior toward at least three women within the agency. “I’ve experienced him yelling at me in meetings,” she wrote, adding that he had demanded preferential treatment and asked staff to violate state laws. “So far, the direction I’ve received has primarily been that I should listen, be cooperative, and communicative.” Avangrid and Walsh, who has since left his position at the company, denied asking DNR to violate any state laws.

DNR spokespeople said the agency addressed some of Haffner-Ratliffe’s specific concerns, like making sure managers were present in meetings with Walsh and giving staff the authority to end meetings or phone calls if they became uncomfortable. Nevertheless, Haffner-Ratliffe left the agency in January 2023. In her resignation letter, she said she was leaving because of a “lack of support” and “unprofessional behavior by clients and peers going unaddressed.”

Haffner-Ratliffe declined a request to comment for this story.

Walsh told HCN and ProPublica that Avangrid conducted an internal investigation into his conduct and cleared him of any wrongdoing. Avangrid declined to comment on Walsh’s claim.

Palmer continued to advocate for accurate documentation of cultural resources. On Oct. 31, 2022, Tetra Tech updated its cultural survey to reflect some of Palmer’s findings, listing more stone structures.

But Palmer told DNR colleagues that the updates were inadequate. “A number of resources that I have observed in the field are not included in this documentation or in previous documentation I have seen from Tetra Tech,” she wrote in an email obtained through a public records request.

Palmer added that date estimates were also off, and some stone features were mischaracterized as natural formations, while others were missing entirely.

Still, in May 2023, Avangrid submitted Tetra Tech’s updated survey, which then became available to the Colville Tribes and Yakama Nation for feedback.

Avangrid representatives said they were unaware of the issues with the initial survey and, when they became aware of them, modified their project plans to accommodate the tribally significant sites. They acknowledged that the state concluded that the updates were inadequate.

A number of tribal officials and sources in state agencies told HCN and ProPublica that tribal opposition to a cultural survey rarely, if ever, makes a difference. But this time it did.

The permitting authority for the Badger Mountain project is a state agency called the Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council. The agency has the power to recommend proposed renewable energy developments to the governor for project permits. Additionally, it will produce the environmental impact statement and oversee the process of satisfying state environmental regulations.

The Colville Tribes and Yakama Nation both filed official comments with EFSEC stating that Tetra Tech’s updates failed to address their concerns. According to the Colville Tribes’ comments, the survey included only four of the archaeological sites that Palmer had found and missed additional sites recorded by a Colville tribal archaeologist. The Yakama Nation requested a full redo of Tetra Tech’s cultural survey by an independent third party. And this time, tribal concerns were echoed by comments from DNR and the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation.

By October 2023, EFSEC commissioned an independent cultural survey. Karl Holappa, EFSEC’s public information officer, told HCN and ProPublica that agency leaders do not recall ever previously commissioning an independent cultural survey, and a public records request shows that there’s no record of one at least in the past decade.

Holappa said in an email that EFSEC took this step to “ensure confidence in the outcome of the Survey by all parties.” He added that the new cultural survey will replace Avangrid’s and that the date of completion will partly depend on when the snow melts, making the ground visible again.

The new cultural survey doesn’t necessarily mean that EFSEC will recommend against issuing a permit for the Badger Mountain project. “I’ve never had EFSEC stop a project on cultural resources — not that I’m aware of,” said Allyson Brooks, the historic preservation officer in charge of the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Holappa said EFSEC doesn’t have the authority to stop a project during the site evaluation process. DNR and the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation also said they lack the power to approve or deny a project.

Still, EFSEC can advise the governor not to permit the project, and DNR could also withhold a lease. State law does authorize agencies to deny a proposed project if it would have significant impacts and insufficient mitigations.

In an email to HCN and ProPublica, Holappa said EFSEC thoroughly examines impacts on cultural resources and tribal concerns during the site evaluation process. “EFSEC will complete its review before making any recommendation to the Governor either to reject this project, to approve it as proposed, or to approve it with additional conditions,” he wrote.

Oliver, the Yakama Nation archaeologist, said having tribal nations take the lead on renewable energy development would be one way to solve the bigger problem. “They’re the ones who have the knowledge” to avoid sensitive sites, he said. The developers themselves can also include tribes: For the Lund Hill renewable project, Avangrid contracted directly with the Yakama Nation to survey the land. Oliver also recommended the state survey public lands and catalog cultural resources before any developers propose projects.

Brooks, the state historic preservation officer, has been working with the governor’s office on a pilot project to do that, allocating about half a million dollars for the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation to inventory cultural resources on some state lands.

Some critics say that plan still overlooks the core issue: Federal and state governments don’t recognize tribal nations’ authority to stop or alter development projects that threaten cultural resources on off-reservation lands where they hold legal rights.

“It's incredibly important for tribal nations to have a decisive say over their land, territories, resources and people,” said Fawn Sharp, vice president of the Quinault Indian Nation and former president of the National Congress of American Indians. “For us to fully engage and fully exercise the broad spectrum of authorities that are inherent to our sovereign interests, we absolutely must have free prior and informed consent as a recognized policy.”

Meanwhile, the Yakama Nation is using federal funds to build solar panels of its own, in a way that it says supports tribal communities. “Non-carbon emitting energy projects are positive advancements our state and country needs, but not at the cost of our traditional grounds and resources,” Yakama Nation officials wrote in an emailed statement to HCN and ProPublica. “Yakama Nation supports responsible energy development efforts. The Badger Mountain project, and the developer’s approach to advancing the project, fall far short of responsible energy development.”

In early 2023, Palmer left DNR, in part due to her frustration with the Badger Mountain project. “I would like to think that we can model a better way to do rural economic development,” she told HCN and ProPublica. “I would like to think there are alternative ways of operating that aren't just corporations preying on people, and no regulation.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with High Country News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with High Country News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Mariam Elba contributed research.

Mariam Elba contributed research.