Rare paper type found at Newberry Library, largest example in existence.

A mysterious manuscript donated by railroad tycoon Edward Ayer.

December 21st 2024.

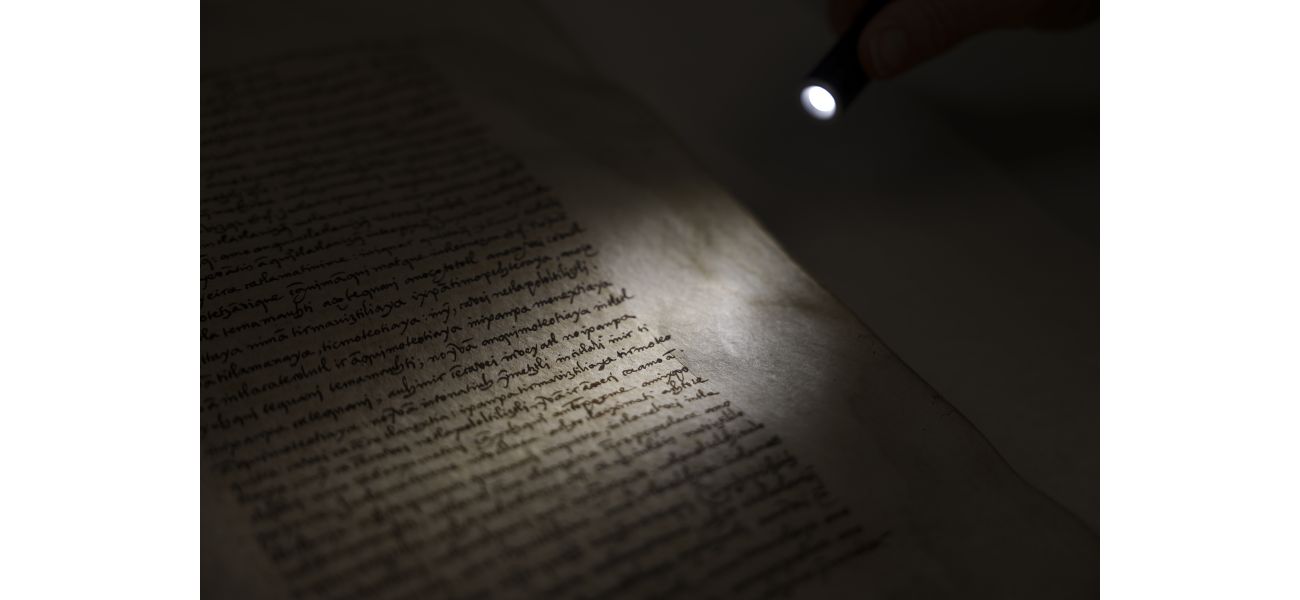

For over a hundred years, a mysterious manuscript had been resting on the shelves of the Newberry Library. It had been donated in 1911 by Edward Ayer, a wealthy tycoon known for supplying ties to railroad companies. The library catalog labeled it as "Ayer 1485," but not much else was known about the ancient book from colonial Mexico.

However, at a Nahuatl conference at Harvard University two years ago, the manuscript gained newfound attention. Pages from the book were projected onto a big screen, bringing together experts of the Aztec language for their first in-person conference since the pandemic. It was a heartwarming reunion for many attendees.

One of the speakers at the conference was Ben Leeming, an independent scholar who specializes in Nahuatl writings used to evangelize Native peoples. As he discussed the significance of the words on the manuscript's pages, art history professor Barbara Mundy became captivated by the images being shown. She couldn't help but ask Leeming to zoom in on the paper itself, which appeared to be made from a type of paper that was not of European origin.

Mundy's hunch led to an astounding discovery made by the Library of Congress. After analyzing the papers, they found that the manuscript was printed on maguey paper, a rare type made from pounded agave plants. Only 10 sheets of this type of paper were known to exist, with four at the Library of Congress and six at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. The Newberry Library's manuscript, titled "A Sequence of Sermons for Sundays and Saints' Days," consisted of 49 sheets.

The library's director of conservation, Kim Nichols, described the excitement that came with this discovery. It was a rare and special moment to see something ancient survive through the years, especially considering the many reasons why such items are often lost.

According to records, Ayer had acquired the manuscript in 1886 from a rare book dealer in London. Its first known owner was a Mexican collector and bibliophile, and it had changed hands at least twice before ending up in Ayer's possession. The manuscript was among the 17,000 items related to Native peoples that Ayer had donated to the library, as he was also a trustee there.

The theory that the manuscript was made of maguey paper had been around since 2000, when a library staffer mentioned it in a conservation report. In a 2017 report, another staffer had placed a question mark next to the guess, unsure of its accuracy. And even at the Nahuatl conference, Mundy initially believed the paper to be amatl, a type made from the inner bark of fig trees.

However, after discussing with Leeming and other experts, it became clear that the manuscript was indeed made from maguey paper. This type of paper, which is made from the same plant as tequila, had been used to write Sahagún's sermons during the colonial era. It was a technology that had become extinct after the arrival of Europeans to the Americas.

In contrast, European paper had been imported to Mexico and used for the famous Florentine Codex, an encyclopedia of Aztec history and belief written by Sahagún. The surviving maguey manuscripts, including Sahagún's sermons, were all from the colonial era.

Mundy had originally thought that the manuscript was written on amatl paper, which was more common and is still being produced today. However, most colonial-era amatl manuscripts are only a single sheet long, making the 49 sheets of Sahagún's sermons a significant find. And after the Nahuatl conference, Mundy and Mary Elizabeth Haude, a paper conservator from the Library of Congress, visited the Newberry Library to see the manuscript in person.

The discovery of maguey paper in Sahagún's sermons shed new light on the history and technology of papermaking in Mexico during the colonial era. It was a reminder of the many lost and forgotten traditions and practices of the past, and a testament to the enduring nature of ancient artifacts. Thanks to Mundy's curiosity and the collaboration between different institutions, the mysterious manuscript on the shelves of the Newberry Library had finally revealed its secrets.

For over a hundred years, the ancient manuscript had been resting quietly on the shelves of the Newberry Library. It was a mysterious and intriguing book from colonial Mexico that had been generously donated to the library in 1911 by Edward Ayer, a collector and tycoon who had made his fortune supplying ties to railroad companies. In the library's catalog, it was simply known as "Ayer 1485".

But it wasn't until two years ago, at a Nahuatl conference held at Harvard University, that the manuscript truly came to life. The conference was the first time experts of the Aztec language had gathered since the pandemic, and it was like a long-awaited family reunion. One attendee fondly recalled the experience of seeing the manuscript's pages projected onto a big screen.

At the podium was Ben Leeming, an independent scholar who specialized in Nahuatl writings used to evangelize Native peoples. As he shared images of the manuscript and discussed its significance, Barbara Mundy, a professor of art history at Tulane University, found herself captivated by the physical pages themselves. She couldn't help but ask Leeming to zoom in on the paper, which clearly wasn't of European origin.

This sparked Mundy's curiosity, and she convinced the Library of Congress to analyze the papers in the fall of 2024. The results were astounding. The manuscript was printed on maguey paper, a rare type made from pounded agave plants. In fact, only 10 sheets of this paper were known to exist, with four being held at the Library of Congress and six at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. The Newberry's manuscript was a whopping 49 sheets long.

The director of conservation at the Newberry Library, Kim Nichols, was thrilled with this discovery. She explained that it was always exciting to see something ancient survive the test of time, as there were countless ways in which it could have been lost.

According to the library's records, Ayer had acquired the manuscript in 1886 from a rare book dealer in London. It had previously belonged to a Mexican collector and bibliophile, with at least two other owners in between. Titled "A Sequence of Sermons for Sundays and Saints' Days", the manuscript was written by Bernardino de Sahagún between 1540 and 1563, and was among the 17,000 items related to Native peoples that Ayer had donated to the library.

The idea that the manuscript was made of maguey paper had been floating around since 2000, when a library employee speculated about it in a conservation report. However, it wasn't until Mundy's hunch and subsequent investigation that this theory was confirmed. Interestingly, the paper was originally thought to be amatl paper, made from the inner bark of fig trees. But upon closer examination, it was found to be maguey paper, made from the same plant as tequila.

Mundy had initially believed that the manuscript was made of amatl paper, as it was more common and still produced today. In fact, there are hundreds of surviving colonial-era amatl manuscripts, although most are only a single sheet long. In a previous article, Mundy had even noted that 49 sheets of amatl paper was a significant amount, possibly the largest collation in existence.

After the Nahuatl conference, Mundy returned to Washington, D.C., where she had a fellowship at the Library of Congress. She shared her findings with Mary Elizabeth Haude, a paper conservator at the library, and the two of them visited the Newberry library in the summer of 2022 to see Sahagún's sermons for themselves. It was a thrilling and unexpected discovery, shedding new light on this ancient manuscript and its origins.

However, at a Nahuatl conference at Harvard University two years ago, the manuscript gained newfound attention. Pages from the book were projected onto a big screen, bringing together experts of the Aztec language for their first in-person conference since the pandemic. It was a heartwarming reunion for many attendees.

One of the speakers at the conference was Ben Leeming, an independent scholar who specializes in Nahuatl writings used to evangelize Native peoples. As he discussed the significance of the words on the manuscript's pages, art history professor Barbara Mundy became captivated by the images being shown. She couldn't help but ask Leeming to zoom in on the paper itself, which appeared to be made from a type of paper that was not of European origin.

Mundy's hunch led to an astounding discovery made by the Library of Congress. After analyzing the papers, they found that the manuscript was printed on maguey paper, a rare type made from pounded agave plants. Only 10 sheets of this type of paper were known to exist, with four at the Library of Congress and six at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. The Newberry Library's manuscript, titled "A Sequence of Sermons for Sundays and Saints' Days," consisted of 49 sheets.

The library's director of conservation, Kim Nichols, described the excitement that came with this discovery. It was a rare and special moment to see something ancient survive through the years, especially considering the many reasons why such items are often lost.

According to records, Ayer had acquired the manuscript in 1886 from a rare book dealer in London. Its first known owner was a Mexican collector and bibliophile, and it had changed hands at least twice before ending up in Ayer's possession. The manuscript was among the 17,000 items related to Native peoples that Ayer had donated to the library, as he was also a trustee there.

The theory that the manuscript was made of maguey paper had been around since 2000, when a library staffer mentioned it in a conservation report. In a 2017 report, another staffer had placed a question mark next to the guess, unsure of its accuracy. And even at the Nahuatl conference, Mundy initially believed the paper to be amatl, a type made from the inner bark of fig trees.

However, after discussing with Leeming and other experts, it became clear that the manuscript was indeed made from maguey paper. This type of paper, which is made from the same plant as tequila, had been used to write Sahagún's sermons during the colonial era. It was a technology that had become extinct after the arrival of Europeans to the Americas.

In contrast, European paper had been imported to Mexico and used for the famous Florentine Codex, an encyclopedia of Aztec history and belief written by Sahagún. The surviving maguey manuscripts, including Sahagún's sermons, were all from the colonial era.

Mundy had originally thought that the manuscript was written on amatl paper, which was more common and is still being produced today. However, most colonial-era amatl manuscripts are only a single sheet long, making the 49 sheets of Sahagún's sermons a significant find. And after the Nahuatl conference, Mundy and Mary Elizabeth Haude, a paper conservator from the Library of Congress, visited the Newberry Library to see the manuscript in person.

The discovery of maguey paper in Sahagún's sermons shed new light on the history and technology of papermaking in Mexico during the colonial era. It was a reminder of the many lost and forgotten traditions and practices of the past, and a testament to the enduring nature of ancient artifacts. Thanks to Mundy's curiosity and the collaboration between different institutions, the mysterious manuscript on the shelves of the Newberry Library had finally revealed its secrets.

For over a hundred years, the ancient manuscript had been resting quietly on the shelves of the Newberry Library. It was a mysterious and intriguing book from colonial Mexico that had been generously donated to the library in 1911 by Edward Ayer, a collector and tycoon who had made his fortune supplying ties to railroad companies. In the library's catalog, it was simply known as "Ayer 1485".

But it wasn't until two years ago, at a Nahuatl conference held at Harvard University, that the manuscript truly came to life. The conference was the first time experts of the Aztec language had gathered since the pandemic, and it was like a long-awaited family reunion. One attendee fondly recalled the experience of seeing the manuscript's pages projected onto a big screen.

At the podium was Ben Leeming, an independent scholar who specialized in Nahuatl writings used to evangelize Native peoples. As he shared images of the manuscript and discussed its significance, Barbara Mundy, a professor of art history at Tulane University, found herself captivated by the physical pages themselves. She couldn't help but ask Leeming to zoom in on the paper, which clearly wasn't of European origin.

This sparked Mundy's curiosity, and she convinced the Library of Congress to analyze the papers in the fall of 2024. The results were astounding. The manuscript was printed on maguey paper, a rare type made from pounded agave plants. In fact, only 10 sheets of this paper were known to exist, with four being held at the Library of Congress and six at the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. The Newberry's manuscript was a whopping 49 sheets long.

The director of conservation at the Newberry Library, Kim Nichols, was thrilled with this discovery. She explained that it was always exciting to see something ancient survive the test of time, as there were countless ways in which it could have been lost.

According to the library's records, Ayer had acquired the manuscript in 1886 from a rare book dealer in London. It had previously belonged to a Mexican collector and bibliophile, with at least two other owners in between. Titled "A Sequence of Sermons for Sundays and Saints' Days", the manuscript was written by Bernardino de Sahagún between 1540 and 1563, and was among the 17,000 items related to Native peoples that Ayer had donated to the library.

The idea that the manuscript was made of maguey paper had been floating around since 2000, when a library employee speculated about it in a conservation report. However, it wasn't until Mundy's hunch and subsequent investigation that this theory was confirmed. Interestingly, the paper was originally thought to be amatl paper, made from the inner bark of fig trees. But upon closer examination, it was found to be maguey paper, made from the same plant as tequila.

Mundy had initially believed that the manuscript was made of amatl paper, as it was more common and still produced today. In fact, there are hundreds of surviving colonial-era amatl manuscripts, although most are only a single sheet long. In a previous article, Mundy had even noted that 49 sheets of amatl paper was a significant amount, possibly the largest collation in existence.

After the Nahuatl conference, Mundy returned to Washington, D.C., where she had a fellowship at the Library of Congress. She shared her findings with Mary Elizabeth Haude, a paper conservator at the library, and the two of them visited the Newberry library in the summer of 2022 to see Sahagún's sermons for themselves. It was a thrilling and unexpected discovery, shedding new light on this ancient manuscript and its origins.

[This article has been trending online recently and has been generated with AI. Your feed is customized.]

[Generative AI is experimental.]

0

0

Submit Comment