This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Maine Monitor. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Maine Rarely Sanctions Residential Care Facilities Even After Severe Abuse or Neglect Incidents

Federal regulations require insurers to promptly hand over records to patients facing claim denials. Some insurers only turned over their files after ProPublica reached out.

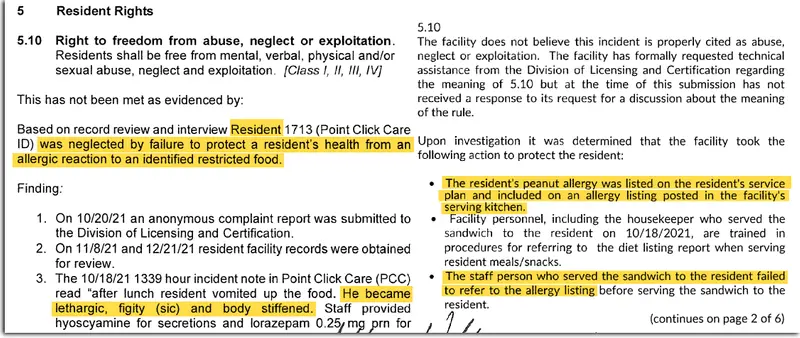

One lunchtime in 2021, a longtime resident at Woodlands Memory Care of Rockland started throwing up. His fingernails turned purple, and his skin became red all over. He was lethargic and fidgety, and his breathing grew shallow, according to the facility’s daily care notes.

The resident was well known at this residential care facility in Maine’s Midcoast region. Former facility employees told The Maine Monitor and ProPublica that he was a nationally renowned concert pianist who continued to play a portable keyboard in his room even as his Alzheimer’s disease advanced.

It wasn’t until a family member arrived and asked if the resident had eaten peanuts that employees realized that he was having an allergic reaction to the peanut butter sandwich that he had been served for lunch, according to the facility care notes. Staff used an EpiPen to treat his anaphylactic shock and took him to the hospital. He died days later, though no official records were made available that show the cause of his death.

The employee who gave the sandwich to the resident wrote in the facility care notes the day after the incident that they “didn’t know” that the resident “was allergic to peanuts.”

In interviews with the Monitor and ProPublica, however, four former employees said the resident’s severe peanut allergy had been documented throughout the facility: in his resident profile, in his room and posted in the kitchen.

“It said it everywhere you looked around him that he was allergic to peanut butter,” said Stacy Peterson, who served as the human resources coordinator at Woodlands of Rockland from 2018 to 2020.

So it was a mystery to the former employees how the resident had been served a peanut butter sandwich that day for lunch.

After receiving an anonymous complaint, the Maine Department of Health and Human Services investigated the incident and cited Woodlands of Rockland for two resident rights violations — first by failing to protect the resident from a severe allergic reaction and the second time by not reporting the case to the state. (The citations do not identify the resident.)

Under state regulations, the health department had the power to impose a fine of up to $10,000 or issue a conditional license that would bar Woodlands of Rockland from accepting new residents for up to 12 months. But it did neither. Instead, it simply required the facility to submit a report, called a plan of correction, stating how it intended to address the deficiencies.

In that plan, Woodlands of Rockland acknowledged that the resident’s allergy had been documented but disputed the health department’s characterization that the facility violated the resident’s rights in the incident. Still, it promised to discipline the employee who served the sandwich and to retrain others on how to handle allergies and to report incidents.

The health department’s modest response to the peanut allergy incident exemplifies its approach to oversight, an investigation by the Monitor and ProPublica found. The health department rarely imposes fines or issues conditional licenses against the state’s roughly 190 largest residential care facilities, classified as Level IV, which provide less medical care than nursing homes but offer more homelike assisted living alternatives for older Mainers.

From 2020 to 2022, the health department issued “statements of deficiencies” against these facilities for 59 resident rights violations and about 650 additional violations — involving anything from medication and record-keeping errors to unsanitary conditions and missed mandatory trainings. Despite these violations, however, it imposed a fine only once: a $265 penalty against a facility for failing to comply with background check rules for hiring employees. And it issued four conditional licenses: three in response to administrative or technical violations and one in response to a variety of issues, including a violation of a resident’s privacy rights.

By contrast, Massachusetts, which has 269 assisted living facilities, doesn’t shy away from imposing stiff sanctions. From 2020 to 2022, the state suspended eight facilities’ operations for regulatory violations.

The paucity of sanctions in Maine comes at a time when Level IV facilities like Woodlands of Rockland — which are similar to what are known generally as assisted living facilities in other states — are expanding their presence in the state. The share of Maine’s population that is 65 or older, 21.7%, is the highest percentage in the country.

As the Monitor and ProPublica have reported, the state’s decision in the mid-1990s to tighten the requirement to qualify for nursing home placement helped spur thousands of older Mainers, many with significant medical needs, to move to these nonmedical facilities — which are subject only to state regulations that hold them to much lower minimum staffing, nursing and physician requirements than nursing homes, which face both state and federal scrutiny.

In stark contrast to how rarely Level IV facilities face sanctions, nursing homes in Maine are often hit with considerable fines for regulatory violations.

Health department spokesperson Jackie Farwell said that plans of correction are often sufficient for improving conditions at facilities. She added that as part of an effort to improve the long-term care system in Maine, the state has been considering rules changes to “establish fines and sanctions as more meaningful deterrents.” But she declined to elaborate on the specifics.

Dan Cashman, spokesperson for Woodlands Senior Living, which runs 14 Maine facilities including the one in Rockland, said the company has “a zero-tolerance policy” and has taken disciplinary actions against any employees who were found to have violated residents’ rights.

Cashman added that the company is in favor of stronger state action against individuals found to have violated residents’ rights to prevent them from working in residential care settings again.

But long-term care advocates say the health department is not doing enough to crack down on facilities, as opposed to individuals, and is allowing poor conditions to persist for vulnerable residents.

Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, a national advocacy group focused on improving nursing homes and assisted living facilities, said stiff sanctions should be imposed more, so that there’s a “meaningful ladder of sufficient penalties to ensure that facilities are properly motivated to take steps to ensure resident safety.”

Otherwise, Mollot said, facilities have no incentive to change their behavior. “To pussyfoot around resident neglect or abuse,” he said, “is essentially encouraging. It’s allowing it to happen.”

A review by the Monitor and ProPublica of state inspection records from 2020 to 2022 shows that the health department employed the lowest intervention possible, even for some of the most serious abuse and neglect incidents.

In the summer of 2021, for instance, a resident at Crawford Commons in midcoast Maine was found to have sexually abused another resident multiple times, according to the state’s investigation. The health department cited the facility for two resident rights violations but only required it to submit a plan of correction.

A year later, a resident in Jed Prouty Residential Care Home in the Penobscot Bay region was found around 6:30 a.m., naked and asleep on the floor, “soaking wet with urine,” after falling sometime after 10 p.m. Witnesses said the resident had been crying for help and complaining of thirst until medics responded. No efforts had been made by staff to move the resident from the floor or provide clothing, according to the state’s investigation. Again, the health department cited the facility for a resident rights violation but only required it to submit a plan of correction.

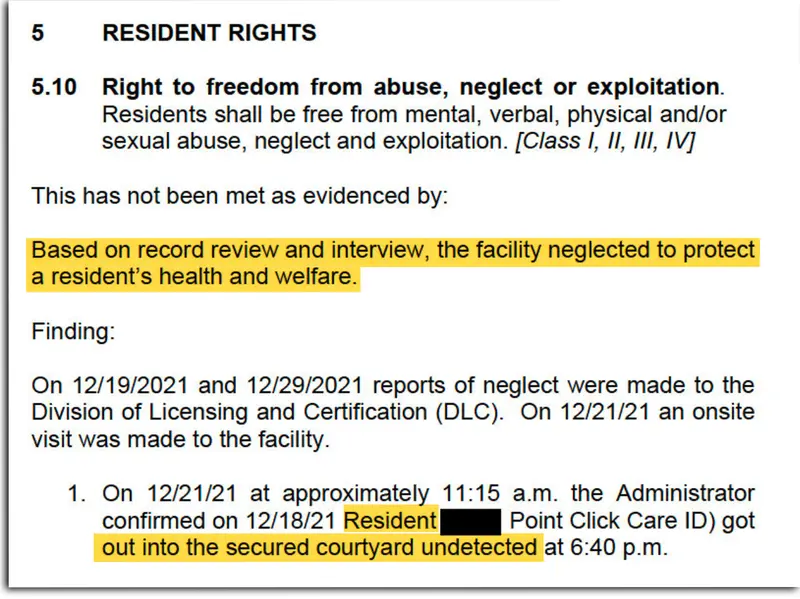

Similarly, in 2021 and 2022, the health department also investigated Woodlands of Rockland for two other serious incidents. In one, a certified nursing assistant at the facility slapped a resident who had spit at and attempted to bite her, according to the state’s investigation. In the other, a resident wandered out to the facility’s locked courtyard, but employees didn’t notice that she was missing until they went to give her medications nearly two hours later, according to the state’s investigation. When the resident was found outside in the snow at around 8:40 p.m., employees wrapped her in blankets and called for emergency medical care. The resident died in hospice days later, and the state investigation cited the cause as “complications of hypothermia.” In the end, both incidents also led to plans of correction.

Woodlands of Rockland has been disputing the health department’s characterization that the facility violated the resident’s rights in the courtyard incident. But Cashman declined to elaborate on the specifics.

Edward Sedacca, CEO of Magnolia Assisted Living, which runs Jed Prouty, said his company took over the operation of the facility in August 2022, a month before the incident, and has since made it a priority to enhance its staffing and training. “The staff we inherited was lacking in overall general knowledge,“ he said. “Magnolia has built an infrastructure well beyond that required under regulation to enable us to provide a higher level of care to all of our residents.”

Crawford Commons did not respond to requests for comment.

For Maine’s nursing homes, however, the response to similar incidents has been very different.

From 2020 to 2022, more than half of nursing homes in Maine received fines — 98 penalties in all, totaling nearly $700,000 — according to U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reports. These fines were imposed in response to a range of violations, including not following COVID-19 infection prevention protocol, making medication errors, not reporting unexpected deaths and failing to protect residents from harm.

In 2020, for instance, an employee at Pinnacle Health & Rehab, a nursing home in Canton in western Maine, “lost it” when a resident became combative, according to CMS investigation records. The employee punched the resident, who ended up with a black eye and bruising around the eyebrow. CMS fined the facility $41,650.

A year later, a resident at Heritage Rehab and Living Center, a nursing home in central Maine, wandered off the premises at night using a walker and was found later by police by the side of a road in the rain. No one at the facility had noticed that the resident was missing, according to CMS investigation records. CMS fined the facility $71,243.

Ken Huhn, administrator of Pinnacle, said the employee was fired, and he made it clear that “that type of behavior would not be tolerated” at his facility.

Heritage did not respond to requests for comment.

Even without the involvement of CMS, which does not regulate assisted living facilities around the country, the health department has the power to adopt a tougher approach toward Level IV facilities. Under state regulations, for instance, it can impose a fine when an incident poses “a substantial probability of serious mental or physical harm to a resident.”

Long-term care advocates told the Monitor and ProPublica that under this standard, some of the egregious abuse and neglect incidents in recent years at Level IV facilities should have resulted in stiff sanctions.

“Because the incidents are so egregious and show such disregard for the well-being of residents, they would have warranted some significant penalty and not just a pro forma requirement that the facility submit a plan of correction,” said Eric Carlson, director of long-term services and support advocacy at Justice in Aging, a national legal advocacy nonprofit focused on ending poverty among seniors.

Paula Banks, who has served as the executive director of another Woodlands facility in Cape Elizabeth and as an assistant administrator of a Maine nursing home, said the fear of such sanctions would be effective. If she were still helping run a residential care facility, she said, it would spur her to take immediate action to address any problems.

“What’s the impetus to change if there’s no consequence?” said Banks, who now runs a geriatric consulting and care management firm.

But Dr. Jabbar Fazeli, who has served as medical director at multiple residential care facilities and nursing homes in Maine, said that rather than imposing sanctions, the state should require more medical attention by increasing nursing hours and requiring a medical director to be on the premises.

“If they had more medical care, I would say 50% of these issues will self-resolve,” Fazeli said.

The health department metes out sanctions in only a small percent of the incidents it hears about each year. Most of the time, it hardly does anything.

To better understand the health department’s process for looking into potential issues, the Monitor and ProPublica analyzed a database of incidents reported to the state by Level IV facilities themselves. Unlike the state inspection records, the database of facility-reported incidents gives a window into what happens earlier in the health department’s enforcement process.

Level IV facilities are required to report an incident to the state when a regulatory violation may have occurred or when a resident’s safety was put at risk. We focused particularly on reports of incidents with the potential for direct harm: the cases of abuse and neglect.

From 2020 to 2022, the state received more than 550 reports of abuse and neglect incidents from Level IV facilities, according to the Monitor and ProPublica analysis. Of those, 342 cases involved residents abusing other residents, 102 cases involved “elopement,” in which residents wandered away unsupervised, and 61 cases involved a staff member abusing a resident.

The analysis shows that in nearly 85% of these incidents, state investigators took “no action” — which, according to Farwell, means that the health department decided not to investigate. She said this could have been for a range of reasons, such as when a facility has already taken corrective action, when state investigators do not expect to find a regulatory violation, or when an incident is being investigated as part of another case or is expected to be reviewed later.

The analysis also shows that the health department did not step up its enforcement even when individual facilities repeatedly reported similar issues.

From 2020 to 2022, 13 Level IV facilities, including Woodlands of Rockland, each had at least 10 abuse and neglect incidents, collectively reporting 348 cases to the state. Even after these facilities had reported multiple cases, the health department still took no action in 91% of them, the analysis shows.

Farwell said state investigators do pay attention to repeated incidents. “If patterns are observed, specific issues may be flagged for follow-up at the next scheduled survey,” she said.

But such follow-ups might not happen for many months, depending on the timing of the next inspection required for license renewal, which takes place only once every two years.

Dionne Mills, who served as the program coordinator at Woodlands of Rockland from 2019 to 2021 and also worked at two other Level IV facilities, said she became aware of the lack of state oversight during her time at the Rockland facility. She said she reported multiple incidents to the state until eventually a state investigator told her that they were too overwhelmed with complaints and that she would have more success taking her concerns to the media.

“The state is so super busy that they only have time to look into the absolute worst-case scenario,” Mills said.

Farwell disputed Mills’ account, noting that state investigators made seven visits to Woodlands of Rockland from 2020 to 2022, the time period when the facility was under investigation for the courtyard, peanut allergy and slapping incidents. Mills’ account “is inconsistent with the number of onsite visits that were conducted at this facility,” she said.

According to Farwell, the health department has 13 investigators — and is in the process of hiring two more — to inspect more than 1,100 assisted housing facilities in the state for license renewals and to investigate any incidents.

Mollot, of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, said the health department needs to do more against facilities with a history of repeated incidents, such as requiring independent monitoring and, possibly, revoking licenses.

“Faced with the fact that these facilities have reported over and over and over and over and over again incidents of abuse and neglect, why have there been a paucity of enforcement acts?” Mollot said.

Several former employees told the Monitor and ProPublica that the history of repeated incidents at Woodlands of Rockland illustrates what can happen to a facility’s standards when the health department takes little enforcement action.

From 2020 to 2022, Woodlands of Rockland had the highest number of abuse incidents reported by a Level IV facility — 48 cases in all, including 38 in which a resident abused another resident, according to the health department database.

But the health department investigated only five of the incidents that Woodlands of Rockland reported, took no action on the rest and imposed no sanctions other than requiring the facility to submit one plan of correction.

With little pressure from the health department, efforts to address recurring problems “were nonexistent when I worked there,” Mills, the former program coordinator, said.

Joshua Benner, who served as a residential care aide at Woodlands of Rockland from 2018 to 2020, said he found it concerning that when the facility was cited by the health department, none of the managers at the facility shared with employees what problems had been found.

“Every other health care place that I’ve ever worked, you have interventions, usually after the state comes in, to go over what you’re dinged on and what can be improved,” said Benner, who has worked at a nursing home and two other residential care facilities.

Cashman, the Woodlands spokesperson, denied that Woodlands of Rockland had “an ongoing or systemic problem” with abuse incidents, noting that the bulk of the cases involved a small number of residents “whose progressively worsening dementia-related behaviors became more and more challenging.”

In response to these residents’ behaviors, Cashman said Woodlands of Rockland has been proactive and taken “multiple interventions,” including resident care plan updates, medication modifications, referrals for hospital treatment and discharge planning.

Cashman said Woodlands of Rockland and its employees have been doing “their best to manage what can be extremely difficult behaviors by individuals living with significant cognitive impairments.”

But Banks said something is amiss if any facility has repeated incidents, noting that she would have been alarmed to see more than one or two incidents of abuse in three years, let alone 30 or more as Woodlands of Rockland did.

“When you have people in your building and you took them in and you told their families you would take care of them and you took their money,” Banks said, “I don’t care what’s going on. I don’t care if you have a staff of three. You’ve got to take care of your people.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Maine Monitor. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Maine Monitor. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Mariam Elba contributed research.

Mariam Elba contributed research.

.jpg)