Tribes in Maine Spent Decades Fighting to Rebury Ancestral Remains. Harvard Resisted Them at Nearly Every Turn.

A vaccine against tuberculosis has never been closer to reality. But its development slowed after its corporate owner focused on more profitable vaccines.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

Donna Augustine was in tears as she read the letter from Harvard University that winter morning in 2013. Looking around the room inside an elementary school on Indian Island, Maine, she saw other elders and leaders from the four Wabanaki tribes were also devastated as they read that the university was denying their request to repatriate ancestral remains to their tribes.

The Wabanaki tribal nations — an alliance of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Mi’kmaq — wanted to rebury the ancestral remains. But Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology said, as it had in past years, that the tribes didn’t have enough evidence to show that they could be tied, through culture or lineage, to the ancestors whose remains the museum held.

The Repatriation Project

A series investigating the return of Native American ancestral remains.

The denial felt like a rejection of Wabanaki identity for Augustine, a Mi’kmaq grandmother, who had spent years urging Harvard to release Native American remains.

“Every one of us in that room was crying,” she recalled. “We jumped through every hoop.”

The group representing the only four tribal nations in present-day Maine had furnished a deeply researched report documenting their histories in the region, even sharing closely held stories passed down within their tribes from one generation to the next that told of their ancient ties to Maine’s lakes, islands and forests.

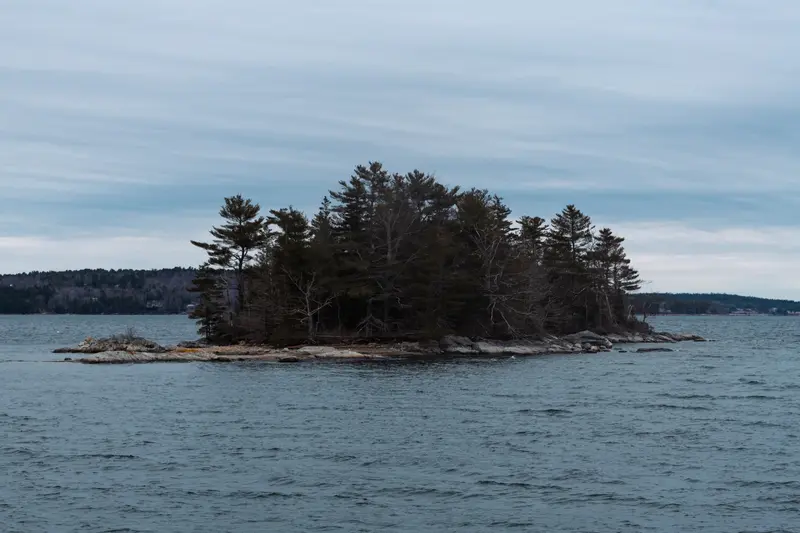

Now they could see it hadn’t been enough for Harvard, which especially prized the remains of 43 ancestors buried for thousands of years near Maine’s Blue Hill Bay.

Complicating matters for the tribes, another museum, the similarly named but smaller Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology, housed on the campus of the Phillips Academy, a Massachusetts preparatory school, held items from the same ancient burial site.

Instead of sending a letter as Harvard did, the Phillips Academy museum director, Ryan Wheeler, had asked to meet with the tribes. Seated at the table that morning, he was initially uncertain what he would do. He would later say that it became evident during the meeting that the tribes exhibited a strong connection to the ancestors they sought to claim, both from the report they had provided and their reaction to Harvard’s decision.

He recalled leaving the meeting certain he would repatriate. “There was really no question about it,” he later said.

What the Wabanaki committee and Wheeler didn’t know, however, was just how hard Harvard would push back. In the two years that followed, the director of the Harvard museum went to surprising lengths to pressure Wheeler to reverse his decision.

A ProPublica investigation this year into repatriation has shown how some of the nation’s elite museums have used their power and vast resources to delay returning ancestral remains and sacred objects under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. By exploiting loopholes in the 1990 law, anthropologists overruled tribes’ evidence showing their ties to the oldest ancestral remains in museums’ collections. We’ve also shown that museums and universities have delayed repatriations while allowing destructive analyses — like DNA extractions — on ancestral remains over the objections of tribes.

Harvard, where the remains of an estimated 5,500 Native Americans are stored at the Peabody Museum, used these loopholes over the span of three decades to prolong the Wabanaki tribes’ repatriation process while remaining in technical compliance with the 1990 law, our review found.

For Augustine and her colleagues, few things were more frustrating than knowing that NAGPRA had empowered museums to decide whether Indigenous people had a valid connection to their ancestors. These were the same institutions that had collected the human remains and objects from ancestral burial sites. Despite NAGPRA’s intent to give Indigenous people say over ancestral remains, institutions still made the final decisions on whether to repatriate.

“The wolves are in charge of how to deal with the sheep,” said Darrell Newell, a former vice chief of the Passamaquoddy Tribe who helped create the Wabanaki Intertribal Repatriation Committee to accelerate negotiations with the institutions. “It’s just not a good way.”

Harvard in recent years has apologized and promised to speed repatriation, saying it aims to repatriate all Native American remains and the items once buried with them within the next three years and recently doubled staffing in the Peabody Museum’s repatriation office. However, the school has yet to return more than half of the human remains it reported holding under NAGPRA, according to federal data from November. Only two institutions, of the hundreds that must comply with NAGPRA, hold more human remains than Harvard.

The university did not provide a detailed explanation to ProPublica regarding its staff’s decisions in the Wabanaki tribes’ case, but it noted in a statement that “each institution, as directed by the NAGPRA legislation, makes its own decisions on repatriation. This can result in institutions making different decisions.”

“To state it plainly, at Harvard, the issue of whether Native American ancestors should be in our collections is clear — they should not,” Harvard President Claudine Gay said last year.

As the Wabanaki people’s struggle with Harvard dragged on, some elders who had been ceremonial leaders died without seeing repatriations come to pass, the committee told ProPublica. In recent years, younger generations helped continue their work, finding that tribes have few options once a museum declines a repatriation request. Among them is Ryan Lolar, a 27-year-old Penobscot Nation descendant and attorney who began helping the Wabanaki committee in 2021.

“Once the museum says no, that’s the end of the road for you,” Lolar said. “As a tribe, all you can do is keep applying, keep reaching out.”

The two Peabody museums have parallel histories. Both are housed in red-brick buildings that hearken to a time when anthropology was a fledgling academic discipline. Each was founded with money from the same Peabody family who, like other wealthy Americans during that era, financed anthropological expeditions and study.

In 1866, George Peabody, who built a fortune in the dry-goods trade and merchant banking, gave $150,000 to Harvard to establish its museum, according to the first annual report. More than 30 years later, his nephew, Robert S. Peabody, a lawyer and alum of the Phillips Academy, founded the prep school’s Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology. A private collector, the younger Peabody seeded his namesake museum’s collection with 38,000 Native American artifacts he had acquired, according to the school.

Both museums sponsored excavations across the United States, which led their archaeologists to Maine. These early archaeologists found no human remains at the burial sites but were in awe of the sophistication of the weapons and tools, fashioned more than 4,000 years ago from stone and the bones of fauna.

Warren K. Moorehead, a director of the prep school’s Peabody Institute, concluded that the people who made the objects, many of them finely etched with geometric patterns, represented a mysterious, vanished culture with no connection to present-day tribes. This theory, while questioned, has persisted into the present, including with an influential archaeologist whose research Harvard has embraced.

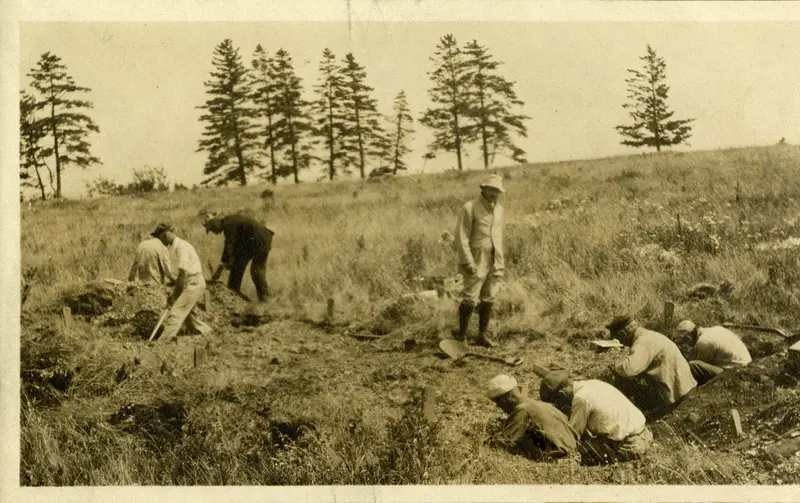

Moorehead had garnered a reputation for rogue and disorganized excavations of tribal ancestral sites in Ohio and New Mexico. He descended on Maine in 1912, emptying 440 burial sites in less than a decade, according to research from Wheeler and Bonnie Newsom, an anthropology professor at the University of Maine and Penobscot Nation citizen.

But Moorehead encountered resistance when he sought to excavate on Indian Island. Penobscot leaders twice blocked him, showing that the Wabanaki people viewed themselves as connected to the ancient people and as protectors of the burials, Newsom said. The Wabanaki nations believed they have been in the region as long as humans have inhabited it.

In the late 1930s, Moorehead’s successor embarked on a dig near Blue Hill Bay. There he unearthed at least 43 ancestral remains and hundreds of items beneath a shell midden, a large, layered stack of clam and oyster shells. Calcium from the shells had counteracted Maine’s acidic soils to preserve the ancestors’ bones. The prep school sent the skeletal remains to Harvard, where curators were interested in studying them. The prep school kept the objects, further intertwining the two institutions — though their decisions about the collection would eventually divide them.

“I’m Going to Come Back and Get You”The passage of NAGPRA in 1990 offered Wabanaki people an opportunity to assert their connection to the region’s ancient people.

Augustine, a mother of seven, was nearly 40 at the time and had already spent more than a decade working on repatriation. The work did not offer pay, but she had willingly committed to it as a spiritual calling, she said. She believed that repatriation restored dignity to generations past and present. She often relied on relatives to watch her children, she recalled, and some summers she didn’t pay her light bill so she could afford the travel.

“How can we tell our children, our youth that they are worth something when at the same time, right over here, there’s a museum and they’re studying our ancestors?” she told ProPublica. “It’s like telling us we’re less-than.”

After the law passed, the tribes formed the intertribal repatriation committee with representatives from each of the Wabanaki tribes. If the four tribes worked through any disagreements before making claims, they could show they were unified when approaching museums.

In the early 1990s, the tribes’ repatriation committee began meeting with the two Peabody museums, as well as with Maine museums that held human remains.

Augustine suspected the institutions wanted to keep the oldest human remains in order to do scientific research. She raised that concern with the institutions repeatedly, including during a visit to Harvard’s Peabody Museum in May 1995, according to a museum document that recounts the visit. At the time, scientific methods like radiocarbon dating helped museums estimate the age of the objects and remains they had found during their expeditions. Yet these methods, like the ancient DNA extractions that would become prevalent years later, required scientists to crush small samples of bone, causing destruction to the ancestral remains.

“We told them, ‘No more science, no more scientific research on those ancestors,’” said Augustine, who, like other tribal members, viewed the research as a violation of tribal beliefs.

Harvard’s museum staff assured her that any researchers who wanted to access the human remains from Maine would likely be told to contact the Wabanaki tribes and that museum policy did not allow destructive analysis without tribes’ permission. Patricia Capone, who has been the museum’s NAGPRA director since the 1990s, was one of several staffers present during the meeting, museum records show.

“It was so hard to leave,” Augustine recalled of the 1995 visit. “I remember telling those ancestors, ‘I’m going to come back and get you.’”

A university spokesperson told ProPublica that the museum’s policies at the time allowed researchers to conduct destructive analysis on the remains. The spokesperson did not address why the Wabanaki tribes had been told otherwise. Capone did not respond to interview requests or questions from ProPublica.

Oral HistoriesIn 2007, Newsom, the Penobscot archaeologist and University of Maine professor, went back to school to pursue a doctorate in anthropology, intent on identifying evidence the Wabanaki tribes could use to support their repatriation claims, she later wrote.

Newsom interviewed people from the four Wabanaki nations and gathered audio recordings of traditional narratives that told of how their cultures first came to be. In the stories, which had been passed from one generation to the next, she identified evidence that the Wabanaki tribes’ time in Maine and Canada’s Maritime Provinces went back thousands of years, and she researched how the narratives could be seen as describing major environmental events.

In one, a Passamaquoddy elder talked about their relationship with a lake near the Canadian border, where the archaeological record shows humans have been present for 8,600 years. Another story linked the Penobscot origins to Cold Stream Pond, north of Indian Island. The stories featured the loon, whale, moose and other animals of the region.

The Wabanaki committee compiled the stories Newsom gathered in a document and gave it to both Peabody museums in 2011.

More than a year later, Harvard rejected the claim. “They just kept coming back, saying that our evidence wasn’t good enough,” Newsom said of Harvard. “It was exhausting.”

But Harvard’s rejection coincided with the tribes’ breakthrough meeting with Wheeler, director of the Phillips Academy’s Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology. His commitment to repatriating the objects at the prep school’s museum came with an understanding, Wheeler said: He would also appeal to the Harvard museum to repatriate the human remains from the same coastal burial site.

After the Indian Island meeting, Wheeler continued to review records and gather input from archaeologists who had studied prehistoric Maine — a topic he was unfamiliar with, having spent his career in Florida. He encountered a range of opinions: Some expressed certainty that the tribes could not have ties to the ancient ancestors and items buried near the bay; or they said they believed the collection was too scientifically valuable to be reburied, which Wheeler noted in his records was not a basis under the law for denying a repatriation. Others said the tribes’ oral histories and other evidence demonstrated a consistent presence in the region well before the time the ancestors were buried near Blue Hill Bay.

“There is more,” Wheeler wrote about his decision to a donor of the preparatory school. “But at a certain point it was clear that the Wabanaki had met the federal standard for their case.”

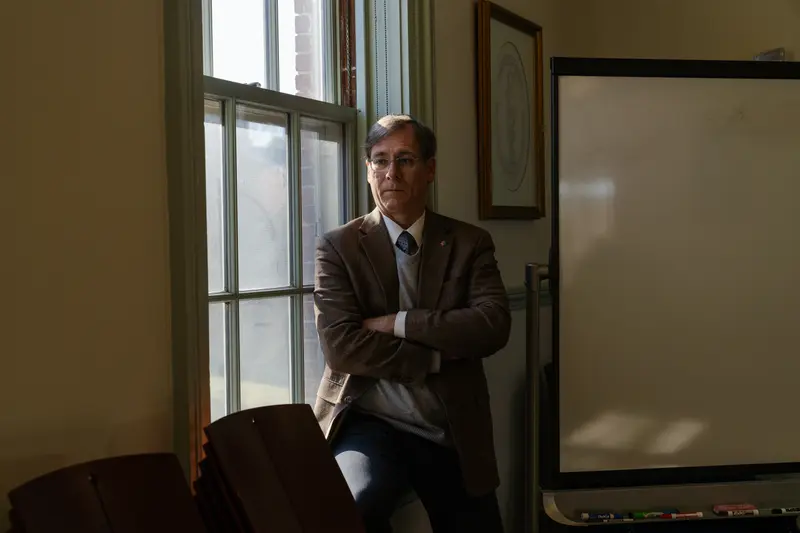

“Entirely Possible”In September 2014, Wheeler drove to Harvard to inform the director of the university’s Peabody Museum, Jeffrey Quilter, that he planned to repatriate the items to the Wabanaki tribes. Quilter wrote in an email that he was shocked following their brief meeting. “Given the close association and intertwined histories of our two museums — particularly in the case of this site — the courtesy of advanced discussion was in order,” Quilter said.

Emails obtained by ProPublica show that Quilter pressured Wheeler to change his mind, saying he believed the decision would result in unwelcome repercussions for the Harvard museum. As part of this campaign, he told archaeologists in Maine that he believed Wheeler’s decision would close the door to future research into the ancient burial site. “The stakes are very high,” Quilter, now a curator in the Harvard museum’s anthropology department and no longer its director, wrote to a colleague.

One of the archaeologists Quilter contacted was Bruce Bourque, the Maine State Museum’s now-retired chief archaeologist. Quilter considered Bourque to be an expert on Maine archaeology. But Bourque, brash and outspoken, also had a reputation for opposing the Wabanaki tribes’ repatriation and water rights claims, saying in an email to Quilter and Capone that the Penobscot people “live in a BIA-funded lala land.” The comment was a derogatory reference to the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ federal trust responsibility to fund basic services in tribal communities.

Bourque told the state attorney general’s office he had received a “panic call” from Harvard about Wheeler’s decision, he said in an email. He emailed another colleague about the news, saying, “NAGPRA has just reared its ugly head.”

“Patricia says Harvard will stand firm,” Bourque wrote of Capone, the university museum’s NAGPRA director. “We should be prepared for a onslaught from the tribes and their fellow travelers, a group of anti-science thugs.”

In an interview and statement to ProPublica, Bourque stood by his comments in the 2014 emails, saying he had been subject to “onslaughts” for his scientific opinions. He added that he had embraced NAGPRA when it was first passed but held the government’s administration of the law in low regard. Quilter, who did not grant an interview, said in an email that he was guided by science in deciding that the human remains from the ancient burial site were not culturally affiliated to Wabanaki people. He also said he believed he was adhering to the law in making his decision.

When Quilter’s efforts to convince the Phillips Academy to reverse its plans went nowhere, he offered another argument why Wheeler should delay repatriating. He said he just learned that the lab of David Reich, a prominent Harvard geneticist, had extracted genetic material from the ancient remains that could shed new light on them.

The disclosure stunned Wheeler.

Reich and his student had provided a document to the Harvard museum describing their research as the first analysis of ancient people from the Northeast that used the whole genome. That brief report — dated October 2013 and marked confidential — offered a broad determination: The ancestors were genetically linked to Indigenous people in North and South America.

Reich viewed his study as inconclusive on the question of the human remains’ connection to present-day Wabanaki tribes, adding that there were no available genetic samples representing modern Wabanaki people that he could use to cross-compare with the ancient DNA, he told ProPublica in an email.

Yet when Wheeler met with Quilter again that fall, Harvard’s staff cited Reich’s paper to argue against returning the items to the tribes, Wheeler said.

Quilter had invited his staff and Bourque to the meeting but dismissed Wheeler’s request to have the director of Harvard’s Native American Program facilitate it, saying he wanted to limit the conversation to archaeological and museum professionals. “If we think we need to include Native Americans then I should discuss how that will happen,” Quilter said. “I just think that adding Native Americans adds another layer of complexity in an already complex situation and do not oppose their participation in principle.”

Ultimately, Wheeler didn’t waver and the prep school’s Peabody Institute proceeded with its repatriation.

(A Harvard spokesperson told ProPublica that the meeting was meant to foster information-sharing among institutions and that the document describing the DNA analysis did not represent official or authoritative results. Quilter said he wasn’t aware at the time that the Wabanaki tribes had asked the museum not to allow research on the remains.)

Reich told ProPublica that he did not know Harvard’s museum used his report to argue against a repatriation to the Wabanaki nations. He also said that he could not rule out that the tribes might be able to trace some of their ancestry to the people buried at the 4,500-year-old site. “It remains entirely possible,” he said.

Newsom was among the first to hear that the ancestral remains had been analyzed, though she didn’t receive the information from the university.

At a March 2015 federal hearing on NAGPRA, more than a year after the Reich Lab reported its DNA results to the Peabody Museum, a woman from a tribe in Massachusetts asked Capone to address a rumor: “I was told that DNA testing was being done on remains at the Peabody Harvard Museum,” said Ramona Peters, of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. “I believe it involved the Wabanaki.”

Newsom, who was in the audience, admits she is surprised, according to a transcript of the hearing. “If there is an institution that is taking it upon themselves to continue to do study, I think that’s ethically wrong until we have an opportunity to present more information or clear up the reasons why we were denied those remains,” she said.

An Interior Department lawyer said the federal committee couldn’t demand that Harvard answer the allegation. And Capone declined to publicly respond to the question, though she offered to have a conversation about NAGPRA and “the museum’s activities.”

Several years later, Newsom said a colleague in Maine confirmed that the DNA analysis had, in fact, happened. She also learned that even though the findings were never published, the Reich Lab had presented a paper on the research at a genetics conference. She searched for a copy, asking colleagues; the librarian at the University of Maine, where she teaches; and the student whose name was on the paper. She hit dead ends.

Augustine, who had asked Harvard not to conduct DNA analysis on the ancestors, felt betrayed by the Harvard museum.

“When they tell us they will not and they do it anyway, well, they’ve lost their credibility,” she told ProPublica.

After fighting for their ancestors for more than 25 years, the Wabanaki made their final formal NAGPRA claim in February 2019 for the human remains held by Harvard. This time, they asked that it happen under a 2010 NAGPRA regulation that allows museums and universities to return remains without saying the tribes have cultural ties to them.

Years earlier, the tribes had passed on a suggestion from Harvard’s Peabody Museum to go this route. It requires only that institutions acknowledge in federal records that the geography of tribes’ homelands encompasses the areas where remains were excavated.

The tribes had always wanted institutions to recognize their cultural connection to the ancestors, but they also wanted to rebury the remains, and four years had passed since the Phillips Academy’s museum had repatriated the burial items to them. “The bottom line was getting our ancestors back no matter what,” said Roger Paul, who is Passamaquoddy and a member of the repatriation committee.

Capone, at Harvard, responded to the tribes’ claim several months later with additional questions but did not say whether she would grant the request. In a recent academic paper, Newsom and Wheeler said the action represented “another tactical strategy” to ensure Harvard would keep the remains.

No ApologyIn the end, it would take an institutional reckoning at Harvard before the Wabanaki tribes could finally collect and rebury the remains of their ancestors.

The same year Harvard stalled in granting the tribes’ final repatriation request, Harvard started to face renewed questions about its ties to slavery and the dark history of many of the Peabody Museum’s holdings. The following year, amid protests over the murder of George Floyd and historical racial injustices, the museum embarked on a review of its collections, which led to an apology from Lawrence Bacow, then the president of Harvard.

“I apologize for Harvard’s role in collection practices that placed the academic enterprise above respect for the dead and human decency,” Bacow wrote in a January 2021 statement. “Our museum collections undoubtedly help to expand the frontiers of knowledge, but we cannot — and should not — continue to pursue truth in ignorance of our history.”

In a separate apology, Jane Pickering, the new director of the Peabody Museum, pledged to prioritize repatriation. The museum now has a policy that requires tribes’ authorization for research on Native American remains and burial items.

The Wabanaki committee used the moment to press the school one last time to relinquish the tribes’ ancestors, drafting a new letter with its lawyers. It was sent to Harvard in April 2021.

“We said, ‘If those are really your values, then return the ancestors that you were holding all this time,’” said Lolar, the Penobscot Nation descendant and attorney.

Pickering responded several weeks later, saying in a letter that the school would release the ancestral remains to the tribes. The school also offered to discuss the DNA analysis, though this has not yet happened

The Wabanaki repatriation committee hoped the Peabody Museum would finally acknowledge its connection with the ancestors, beyond geography. But Pickering’s letter included no such acknowledgment.

And despite the university president’s public apologies for the racial injustices it had perpetuated, no one from Harvard apologized to the Wabanaki.

“Nothing changed about those ancestors in that 30 years,” said Lolar. “It’s just that they never cared about what the tribes were saying all along.”

In September 2021, Augustine and Lolar were among a half-dozen tribal representatives who traveled to the museum for the repatriation. As they carried boxes containing the ancestors’ remains to their vehicles, they passed an exhibit about Penobscot history and culture that a Harvard spokesperson said was created in partnership with tribal representatives. Nearby was a photo display and text stating how the Peabody champions repatriation.

Lolar found it ironic that the museum had so prominently honored his culture with an exhibit while withholding the ancestors for so long. Still, those feelings didn’t obscure the overwhelming relief of the day, Augustine said.

Days later, the group buried the ancestors and items in an undisclosed location.

They couldn’t place them at the original burial site. A road now runs alongside it. After praying about how to proceed, they decided to ceremoniously create a connection between the two burials, old and new. They took soil from the original site and buried it with the ancestors in their new resting place, Augustine said. Then, they took soil from the new site and sprinkled it over the old one.

The Repatriation Project

Get in Touch

Know about an institution resisting repatriation? Have a personal story to share? We’d like to hear from you.

Learn How to Report on Repatriation

Watch an informational webinar with our reporters.

Sign Up for the Newsletter