This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Erasing the “Black Spot”: How a Virginia College Expanded by Uprooting a Black Neighborhood

As a teenager, I competed in track meets at Christopher Newport University. As a reporter, I unearthed the painful history behind the campus’s location.

Katie Luck was sitting in her yard under a magnolia tree one afternoon in April when a school bus passed by. A white elementary school student shouted at her from a window, “You don’t belong here.”

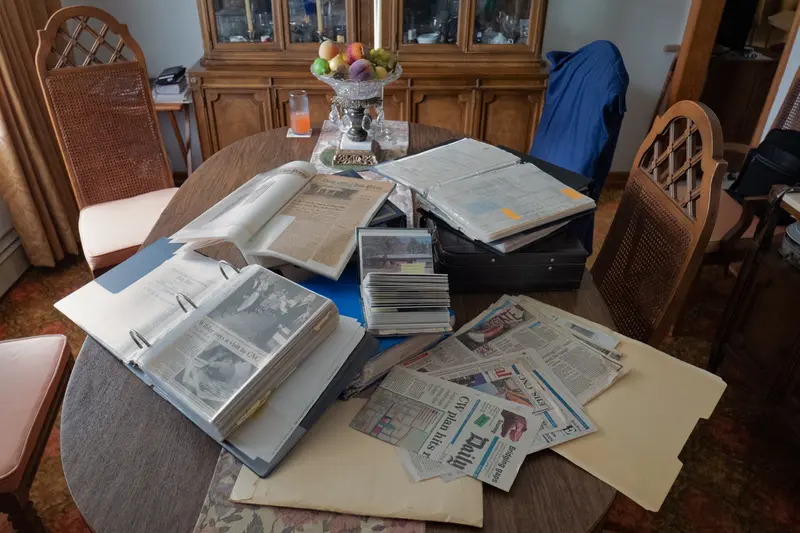

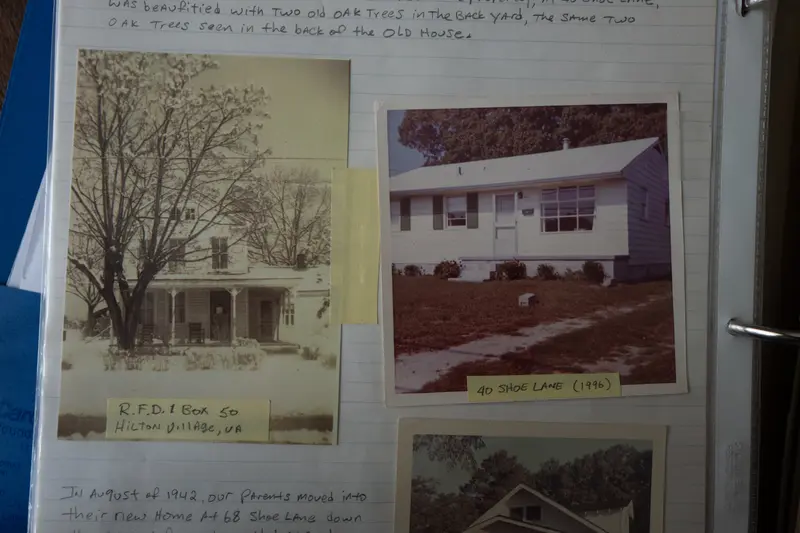

The 81-year-old grandmother and retired teacher, who is Black, was so distressed that she called James and Barbara Johnson, who live down the road from her on Shoe Lane in Newport News, Virginia. The Johnsons, perhaps better than anyone, knew just how wrong the elementary schooler was. The stacks of files and photo albums on their dining room table are a shrine to what the Shoe Lane area used to be — and what it might have become.

Around 1960, in the last gasp of the Jim Crow era, the Shoe Lane community consisted of a church and about 20 Black families, including teachers, dentists, a high school principal and a NASA engineer. They owned ranch-style houses along Shoe Lane and three other streets, which formed a trapezoid enclosing woods and farmland. The Johnsons were planning to sell some of the farmland to Black people who aspired to the American dream of homeownership but were shut out of white neighborhoods by racist banking and zoning policies. The enclave’s population was about to grow.

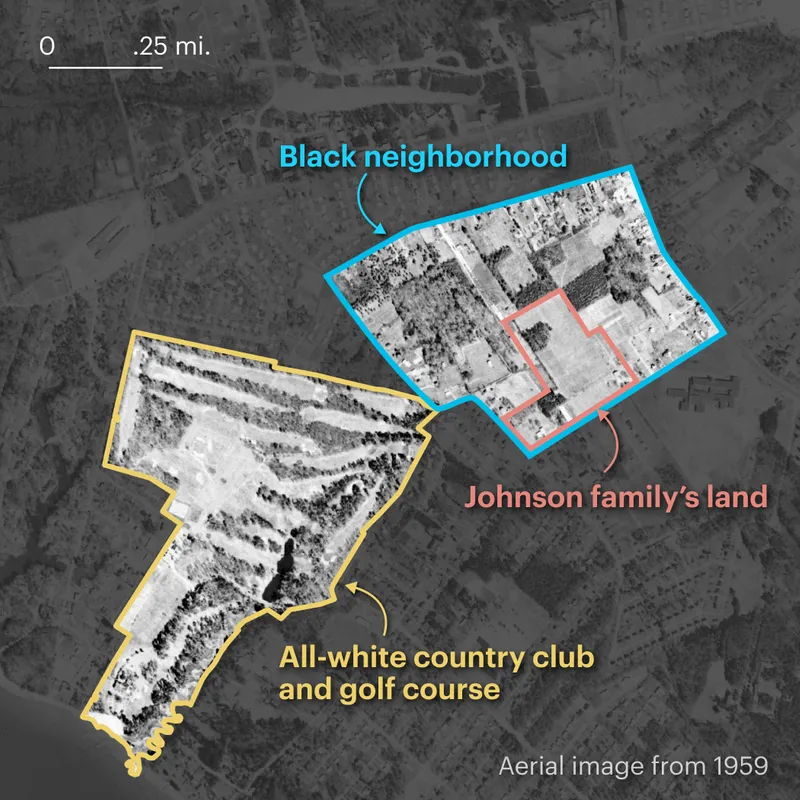

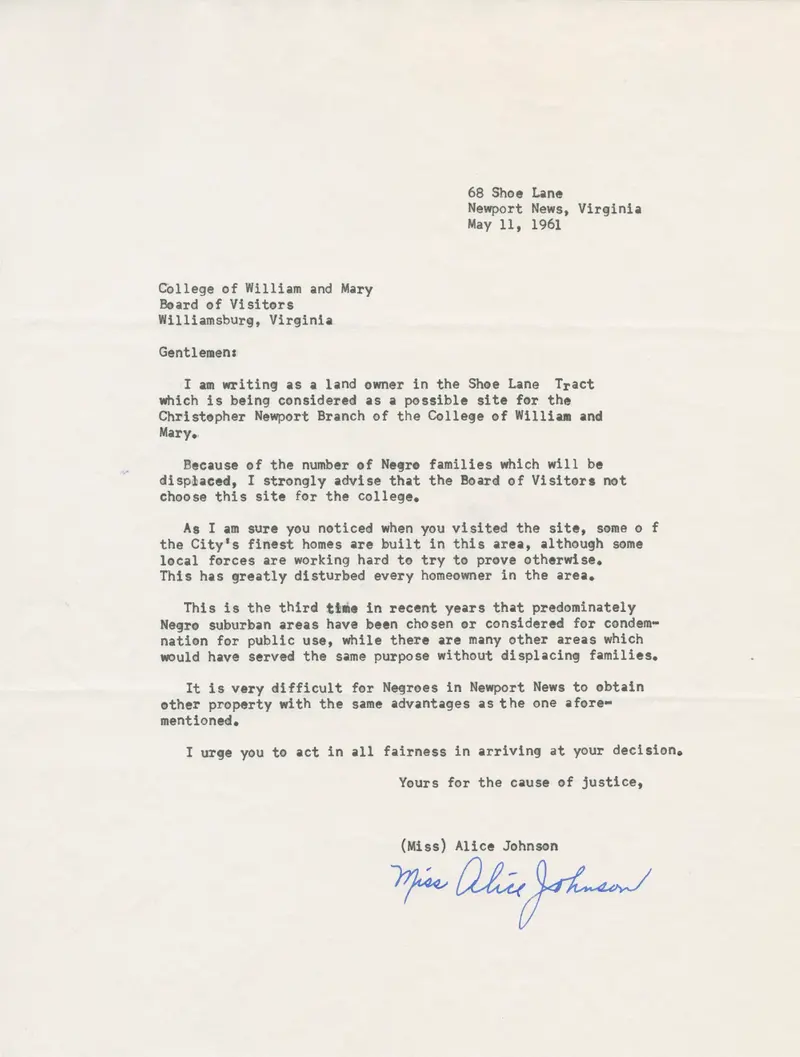

But geography — and racism — were against them. The 110-acre Shoe Lane area lay beside one of the city’s most affluent white sections, where Newport News’ power brokers played golf at a segregated country club. Aware that more Black families would be moving to the area, the Newport News City Council wielded its most powerful weapon: eminent domain, the government’s right to forcibly purchase private property for public use. In 1961, it seized the core of the Shoe Lane area, including the Johnsons’ farmland, for a new public two-year college — a branch of the Colleges of William and Mary system. The council overrode protests from homeowners and civil rights advocates that there were more suitable, and less expensive, sites elsewhere for the college, which today is Christopher Newport University. The city worsened the blow by paying 20% less for the properties than the value set by an independent appraiser, council records show.

The campus location “was almost entirely a racial issue,” said Christopher Newport professor Phillip Hamilton, author of a history of the institution, who examined records including minutes of the City Council’s deliberations. “I believe they wanted to remove the Black community from here. They certainly wanted to halt the arrival of middle-class Blacks.”

The Shoe Lane seizure was an “egregious wrong,” said Anthony Santoro, Christopher Newport’s president from 1987 to 1996. “Historically, the city has to own up to the fact that this was a deliberate attempt to get rid of a Black community, because there were many places that the school could have been built.”

All white at its inception, the college enrolled its first Black student in 1965. It became independent from William and Mary in 1977. As it expanded into a university under Santoro’s leadership, it was eyeing the parts of Shoe Lane that weren’t affected by the initial taking. While it ruled out using eminent domain, it sought to acquire the remaining homes and businesses through traditional sales. Feeling blindsided, homeowners sued the school in 1989. They contended that, because Christopher Newport had extended its boundaries to encompass their houses, they couldn’t sell to anyone else. The case was dismissed.

Santoro’s successor, longtime president Paul Trible, said publicly he wouldn’t need to invoke eminent domain. But his administration used it as leverage to force at least one homeowner to sell in 2005, records show. That same year, the school’s governing board approved its use for three other properties that Christopher Newport said it ultimately acquired without resorting to eminent domain.

Christopher Newport “publicly acknowledges that residents of a valuable and well-established neighborhood were displaced by decisions made about the location of the University,” spokesperson Jim Hanchett said in a statement. “University faculty have spearheaded efforts to raise awareness of this history and its impact. At the same time, the University’s growth has fueled the economic revival of Newport News’ mid-city area.” Trible, who is retired, could not be reached for comment.

Today, only five Black households, including the Johnsons and Katie Luck, are left in the Shoe Lane area. One sits between sorority and fraternity houses and a residence hall; the only street access is through a university parking lot. A dorm and a student center occupy land that the Johnsons hoped to develop.

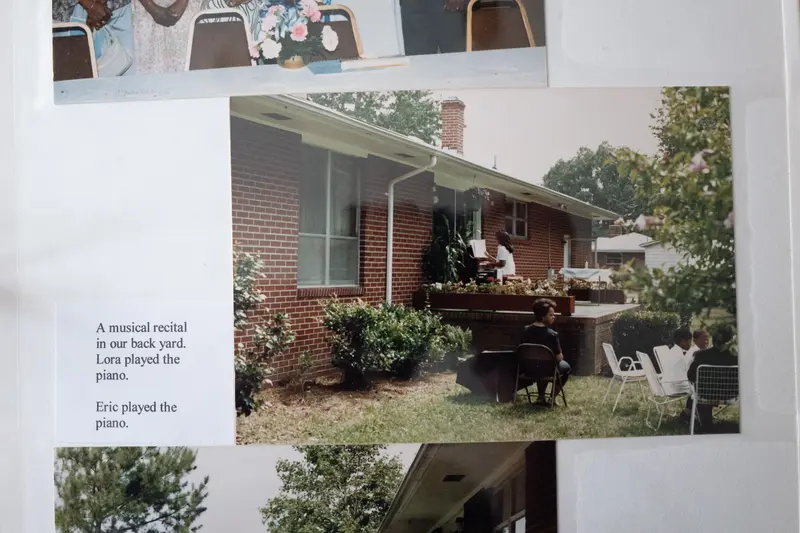

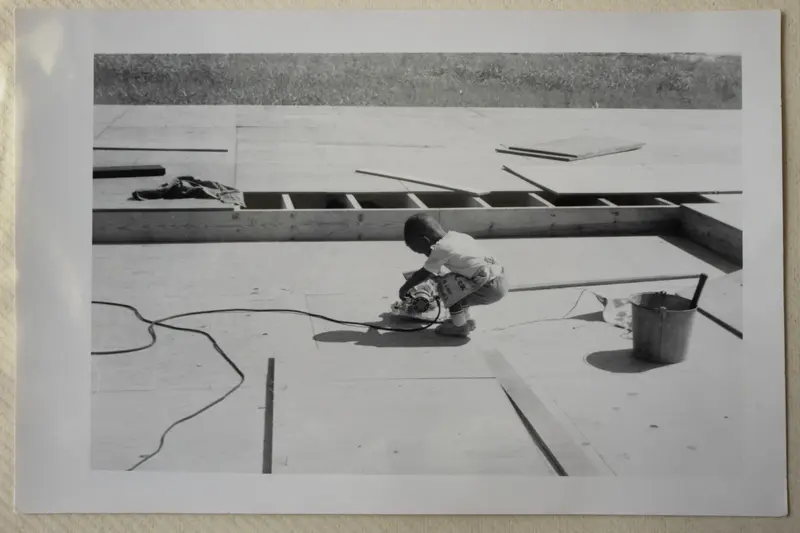

One spring afternoon, the Johnsons sat and reminisced in the home they helped build with their own hands. They’ve lived there since they were married, in their 20s, except when James was in the Army. Now in their 80s, the couple lamented the absence of family and former neighbors, now scattered far and wide.

Their scrapbooks trace the dismantling of a vibrant Black community. Six-decade-old civil engineering maps detail the family’s plans to develop the farmland that was taken by eminent domain. Faded news clippings, carefully snipped and placed in chronological order inside sheet protectors, recount the City Council’s selection of Shoe Lane for the college campus. Rusted metal staples fasten protest letters homeowners sent to college officials and papers from their unsuccessful federal lawsuit.

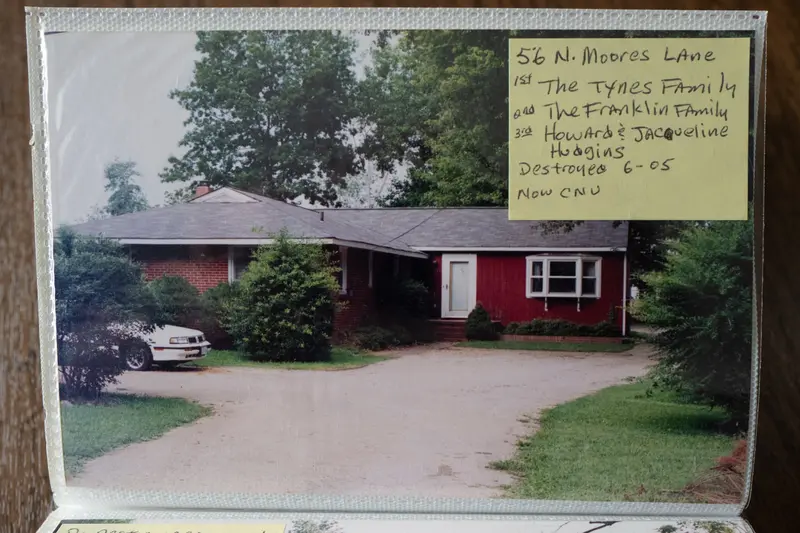

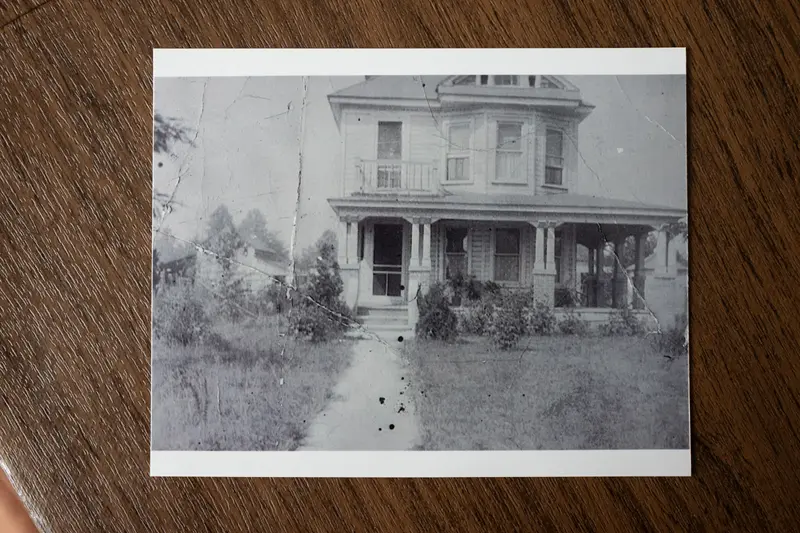

Thumbing through the albums, James Johnson paused suddenly, as if struck by a distant memory. He disappeared into the back of his house and returned with yet two more scrapbooks: pages of original land deeds more than a century old and images of one- and two-story homes photographed hastily before they were demolished in the 1990s and 2000s.

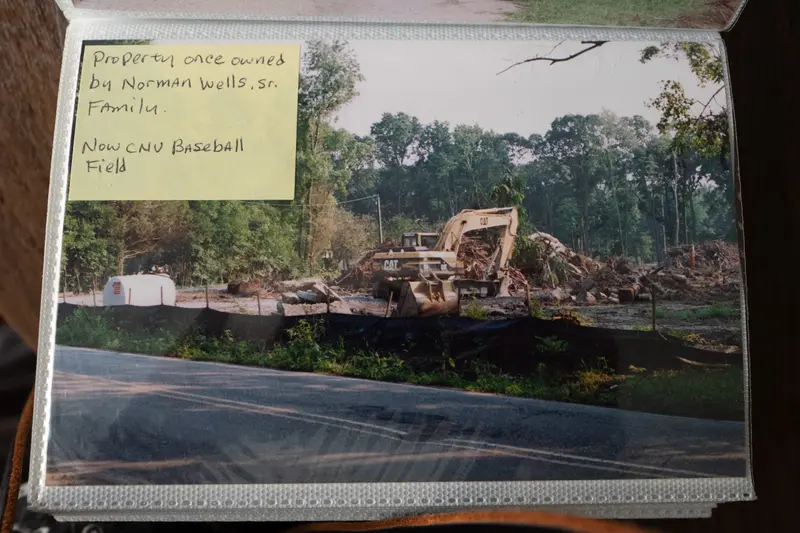

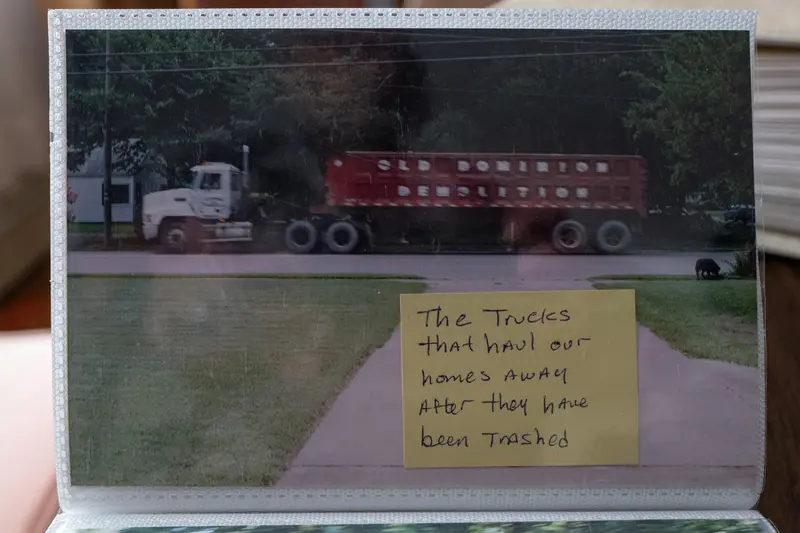

An auto mechanic by trade, Johnson became the self-appointed historian of his vanishing neighborhood. “When things started moving fast, I woke up one morning and told my wife, ‘I got to document this community,’” James said. “This helped me get through.” He peered through his bifocals at a photo of dump trucks carrying debris from houses leveled to make way for the college. Affixed to the photo was a yellow sticky note: “The trucks that haul our homes away after they have been trashed.”

“This was truly a village,” Barbara said. “Young folks don’t know anything about what used to be here.”

James Johnson’s lips curled into a resolute half-smile partially covered by his salt-and-pepper mustache. “I’m the last of the Mohicans,” he said. “All the guys I grew up with moved away. It was hard.

“We’ve known, all over the country, this is what they’ve done to neighborhoods where Blacks are. We all felt it was taken because it was a Black neighborhood.”

As debate rages over the reality of historical and present-day racial discrimination, the Shoe Lane saga illuminates a long-standing aspect of the African American experience: the confiscation and destruction of Black neighborhoods for higher-education facilities in the post-World War II period. A federal program that provided financial incentives for university expansions was responsible for displacing nearly 20,000 families in the U.S. between 1959 and 1966, according to University of Richmond professor Robert Nelson, who has compiled an online database on the topic. While working-class white residents were also dislodged, roughly 40% were Black families, about four times the Black proportion of the U.S. population at the time. Local and state programs expelled thousands more Black families, like the Shoe Lane homeowners, for higher-education projects.

Eminent domain seizures by universities exacerbated the racial gap in homeownership and the widespread loss of Black-owned properties, resulting in “the loss of wealth by African American communities and individual African Americans,” Nelson said. Even those residents who found better housing “still lament the fact that their community and their neighborhood was destroyed.”

University seizures were part of a broader policy of urban renewal, famously dubbed “Negro removal” by author James Baldwin. Touted for improving ramshackle neighborhoods, urban renewal also ravaged thriving communities. Eminent domain was, and remains, its favored tool.

The government has long had broad powers to take property for roads, bridges and infrastructure projects. But in 1954, the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court desegregated public schools in the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the court broadened government authority to acquire land by eminent domain for other public purposes, such as urban renewal. The condemning agency only had to show that some part of the area was poorly maintained.

“If you wanted to, you could find pretty much any neighborhood blighted,” said James Burling, vice president of legal affairs at the Pacific Legal Foundation, a nonprofit that specializes in lawsuits against what it considers government overreach. “There was very little thought about what was going to happen to the people that lived there.”

Across the country, government agencies acquired Black neighborhoods through the use or threat of eminent domain, often for less than market-rate prices. A study by the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest law firm, shows that two-thirds of the 1 million people displaced by eminent domain and urban renewal projects between 1949 and 1973 were Black.

Communities near colleges were especially vulnerable. As the Cold War created a clamor for more scientific training, universities rushed to build classrooms and dorms for the first wave of baby boomers and lobbied Congress for funding and authority to take over surrounding areas. “Without the right of eminent domain,” a vice president of NYU told Congress in 1959, “our institutional planning and development could be totally blocked for the future.” Local officials supported these demands, since universities served as economic-development engines for cities struggling with white flight to suburbia. That same year, an amendment to the Federal Housing Act gave colleges wider latitude — and generous subsidies — to ally with cities to expand into stable neighborhoods.

In the 1960s, some of the nation’s most prominent universities swept into Black neighborhoods. The University of Pennsylvania forced almost 600 families out of a predominantly African American neighborhood known as Black Bottom to make room for a science center, touching off protests and student sit-ins. The University of Georgia leveled Linnentown, a Black community of 50 families, for dorms and parking. The University of Oklahoma took an area of more than 650 Black families in Oklahoma City for a medical center. In Virginia, cities seized Black properties to expand public campuses in Norfolk and Charlottesville, as well as Newport News.

“Small colleges, large colleges, small cities, large cities — it was widespread just in the same way that urban renewal, more broadly, is widespread,” said Virginia Tech professor LaDale Winling, author of “Building the Ivory Tower.”

How Christopher Newport University Uprooted a Black Neighborhood

1959

1961

1999

2023

A statue of jaunty, bearded Christopher Newport, wearing a cavalier hat and leaning on a sword, looms at the entrance to his namesake university. Behind the mariner who transported settlers to the Virginia Colony in the early 17th century lies a campus of brick Colonial and Georgian-style buildings named after public officials, university administrators and wealthy donors.

The land where the 4,500-student university now stands had been a Black community at least as far back as the turn of the 20th century. Black people, likely including freed slaves and their descendants, settled the area, working on farms or at the shipyards, scraping together money for their piece of America. Back then it was a mix of forests, farmland and dirt paths that led to a couple of dozen homes bordered by four streets: Shoe Lane, Moores Lane, Prince Drew Road and Warwick Boulevard.

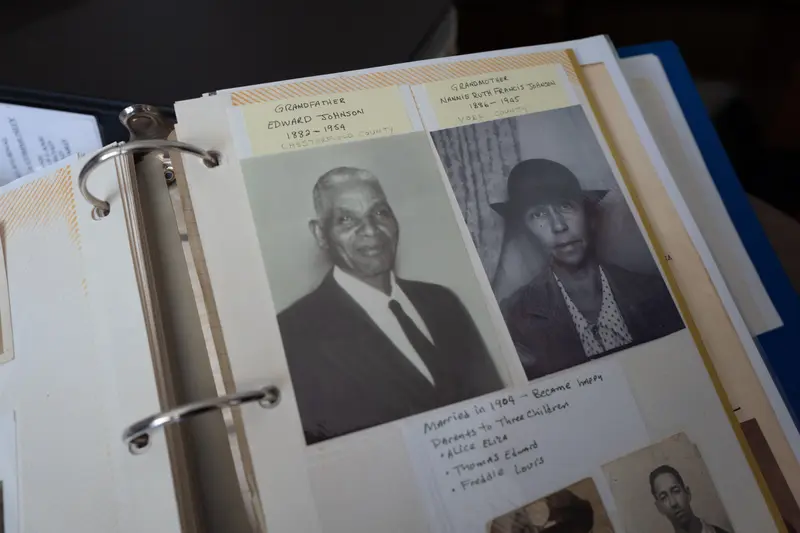

James Johnson’s grandfather Edward Johnson came from Chesterfield, Virginia, about 90 miles north of Newport News. In 1907, he purchased slightly more than 30 acres of land in the Shoe Lane area. Since he could barely read or write, his wife, Nannie, helped him arrange it. Edward raised pigs and grew peas, beans and corn. During World War II, he received a certificate of appreciation from President Franklin Roosevelt for his work with the draft board.

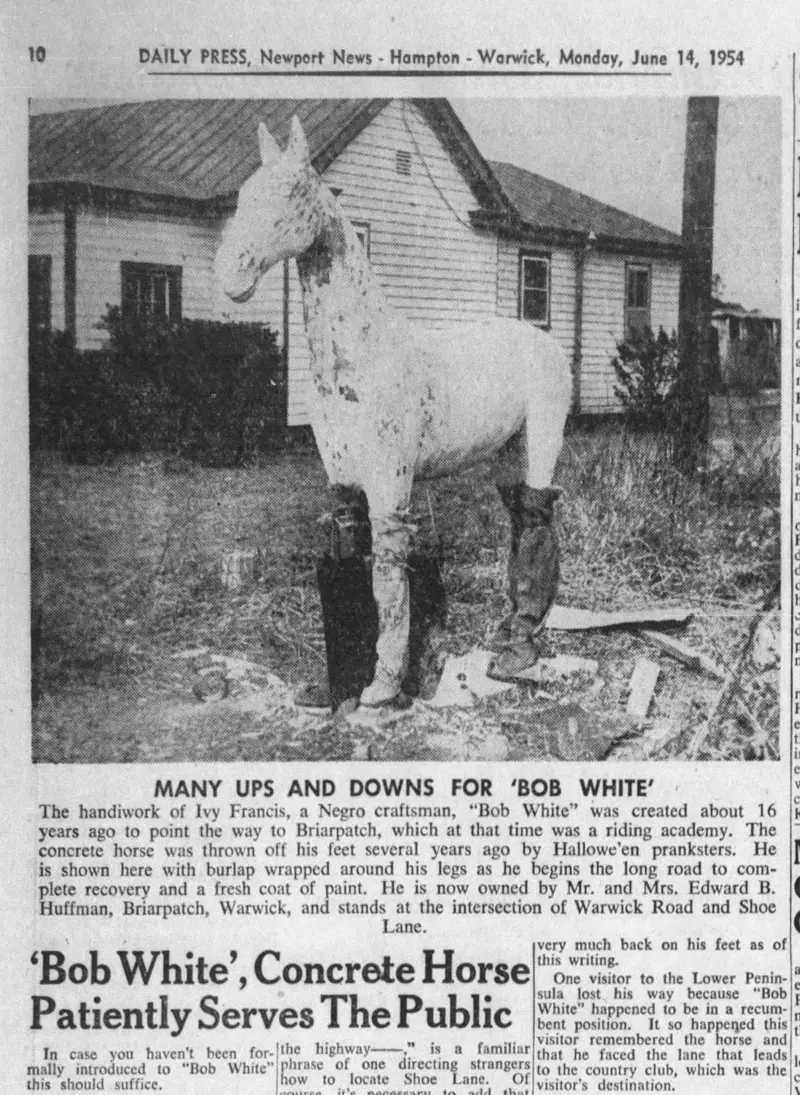

James was born in 1938 and grew up on Shoe Lane, then a dirt road. Across from its entrance, close to where the Christopher Newport statue stands today, one of James’ uncles erected a statue of a horse. It served as a signpost for customers of a horse training school across the street from the Johnsons. As a boy, James made money by charging the school’s patrons to park on his grandfather’s land during riding shows.

“At the end of a day of parking cars, 25 cents a car, I had a pocketful of quarters,” James said. “I thought I was rich.”

The community was remarkably self-sufficient. Neighbors helped build and refurbish each other’s houses and loaned each other money for funeral expenses. Many families were connected by blood or marriage. James’ aunt Alice lived on Shoe Lane and taught Sunday school at nearby First Baptist Church Morrison. She baked and sold brownies to take her class on field trips.

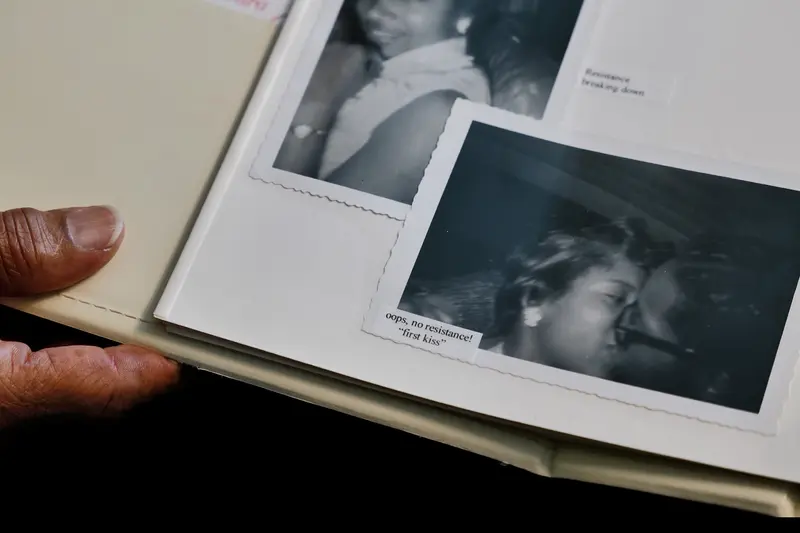

Barbara, James’ future wife, grew up nearby. They met in middle school and began dating in high school. An avid photographer from his early teens, he chronicled their blossoming relationship. He still keeps a selfie, which he took by holding a camera in his outstretched hand, of their first kiss. Barbara played alto sax in the band in high school and at Virginia State University, a historically Black college, graduating with a degree in home economics. James was drafted into the U.S. Army.

In the mid-1950s, many white developers across the country were building suburban subdivisions. Hidenwood, then a whites-only housing development, sprang up around the James River Country Club, adjacent to Shoe Lane. At the time, the Johnsons’ extended family owned several houses and 20 acres of farmland. They had the idea to convert the farmland into lots for middle-class Black families who were excluded from Newport News’ desirable white neighborhoods.

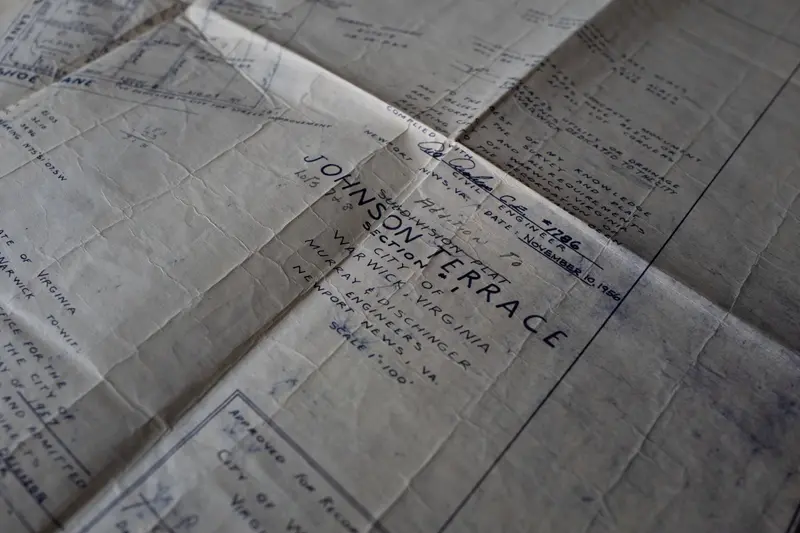

In 1956, the Johnsons started dividing 5 acres on the corner of Shoe Lane and Moores Lane into six lots. With the city’s approval, they sold them to several middle-class Black buyers, including William Walker, a real estate developer. They dubbed the new subdivision Johnson Terrace.

In 1959, the Johnsons began planning to divide their other 15 acres into at least 35 lots. They hired a civil engineer, who drew up plans that included curbs, gutters, a new road and sewers, at a cost of at least $75,000.

The Johnson Terrace project typified the emerging economic and political activism in the Black community nationwide. The Civil Rights Movement was growing, and the Brown v. Board decision was opening opportunities for Black children to learn side by side with white students. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. regularly traveled to the Tidewater area to address church congregations, urging Black parishioners to protest for economic and social equality.

State leaders resisted change. U.S. Sen. Harry F. Byrd Sr., boss of Democratic politics in Virginia for nearly four decades, led a campaign known as Massive Resistance to shutter public schools rather than integrate. Private whites-only schools sprang up.

“As you know, we face a grave crisis in Virginia,” Gov. J. Lindsay Almond wrote to a Norfolk schoolteacher in October 1958. “Mixing of the races will destroy public schools in many areas and seriously militate against their efficient operation in other areas.”

In 1960, only four of Virginia’s 13 predominantly white public colleges enrolled African Americans. Of the 31,000 students in those 13 schools, just 50 were Black. The all-male Virginia Military Institute did not have a single Black cadet until 1968.

The Johnsons’ plans for a Black development soon collided with the ambitions of Newport News’ City Council. As the Cold War boosted production at the shipyards, the local economy was booming, and civic leaders wanted a college to educate and train the workforce. In 1960, the city of Newport News established a William and Mary branch, but it needed a permanent location.

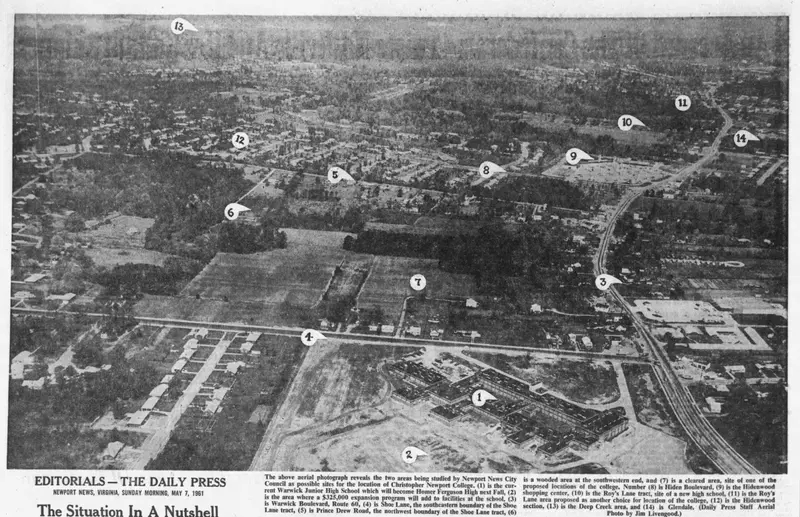

Black residents would have little say in a decision that would drive some of them from their homes. While Black people made up 43% of Newport News’ population in 1950, poll taxes and literacy tests prevented many of them from voting. The city’s 1958 merger with the whiter surrounding county further diluted Black political power. As a result, the mayor and all the city councilors were white. They winnowed at least five potential sites for Christopher Newport College down to two only a three-minute drive apart: a racially integrated area north of Roys Lane, and the Shoe Lane area.

Newport News officials offered race-neutral reasons for considering Shoe Lane and Roys Lane, such as easy commutes for students and proximity to medical facilities. But they had repeatedly targeted neighborhoods where Black people lived for eminent domain takings. Between 1955 and 1960, they seized 30 acres farther east on Shoe Lane and 70 acres on Roys Lane for all-white public schools. Ivy Francis, James Johnson’s great-uncle, lost his Shoe Lane home in that taking and moved up the street, closer to James’ family.

“Does it not seem more than coincidental that, with the hundreds of undeveloped acres in the city, the sites recently chosen by the city for condemnation are sites owned by Negroes?” local civil rights leader C. Waldo Scott, a Black surgeon, wrote in Newport News’ Daily Press newspaper.

Although it’s not clear if the Johnsons submitted their plans for a 35-lot Black development to the city, there’s evidence that Mayor Oscar Brittingham Jr., who chaired the City Council, was aware of them. While the council was considering the Shoe Lane site, Brittingham corresponded with a real estate agent, who told him about discussions he’d had with the Johnsons regarding a residential development.

The Johnson Family’s Land Was Near a Sprawling Whites-Only Golf Course and Country Club

Hamilton, the Christopher Newport historian, said that city leaders likely focused on Shoe Lane because it was close to the all-white James River Country Club. The club’s manager declined to provide member rosters for this article, but indicated that at least one city councilor belonged in the early 1960s. So did the city’s business elite. Even a quarter-century later, when Christopher Newport hired Santoro as president, the club didn’t admit Black or Jewish people. (He said he joined anyway because college board members told him he had to: It was where “all the money people” — prospective donors — were.)

In a series of tense City Council hearings across 1960 and into 1961, Shoe Lane residents fought for their homes. They enlisted two civil rights attorneys, W. Hale Thompson and Philip Walker (William’s brother). Along with helping to integrate the Newport News library, Thompson had represented the Johnson family on business transactions, while Walker had argued desegregation cases alongside famed civil rights lawyer and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

Thompson and Walker contended that cheaper and better vacant sites were available and would not harm the Black community. “It is an indisputable fact that the desirable residential sites for non-white use are extremely limited,” Thompson and Walker said in a public statement. “We implore you to abandon the thought of acquiring the land in this area for public use.”

The homeowners’ white allies included Anne W. Fullman. A devout Methodist and president of Church Women United, Fullman advocated for Black people, women and migrant workers. At a City Council hearing on May 8, 1961, she deplored the “racial overtones” of the proposed purchase. “There are some very fine Negro homes in the Shoe Lane area. There should be fair play and justice for all.” Black families “too like nice homes in nice areas,” she added. “It is harder for them to buy such desirable sites.”

At one point, city councilors said they would rely on guidance from William and Mary’s governing board. The Johnsons pleaded with the all-white board. “Because of the number of Negro families which will be displaced, [we] strongly advise that the Board of Visitors not choose this site for the college,” they wrote. “This has greatly disturbed every homeowner in the area.”

But the college didn’t take a stand, deciding on May 20 that either location would be “entirely suitable,” according to meeting minutes. The board left the choice to the City Council.

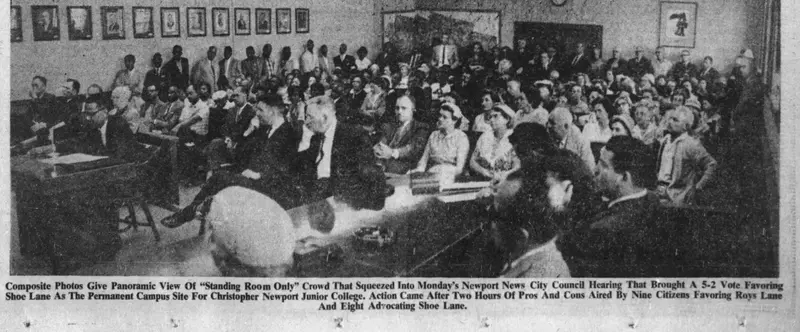

Nine days later, residents packed every seat and lined the wood-paneled council chambers for a special hearing to select the college site. Thompson made a blunt final appeal. The city’s goal, he said, “was to eliminate the possibility of Negroes building homes in that area.” The council surveyed attendees of both races, and a majority favored the integrated Roys Lane as the college site, though most of the white residents preferred Shoe Lane. By a 5-2 vote, the all-white council picked Shoe Lane.

Santoro believes that city leaders at the time wanted to destroy the entire Shoe Lane community. “I had heard that the goal was to wipe it out completely, you know, no houses or anything,” he said. “I was told that that was the plan: It was to erase the Black spot — they called it a ‘Black spot.’ And I didn’t like hearing that at all.”

But “there was such an uproar” that the city narrowed its sights, he said. Enclosed by Shoe Lane and the other three streets, the 60-acre zone designated for the new campus by the City Council was a mix of houses, woods and farmland. James’ home, and his parents’, lay outside its boundary, as did the finished 5-acre subdivision. The zone did include the 15 acres that the Johnsons planned to develop, as well as the house where James’ uncle Ivy had moved after the prior Shoe Lane seizure. He was twice dispossessed.

With the council’s approval, Newport News moved to buy the Shoe Lane properties. Undaunted by the political setback, most of the families refused to sell. The city invoked eminent domain to acquire 18 properties. Laws at the time allowed cities to choose favorable assessed values. Unhappy with an independent appraiser’s assessment of $363,000 combined for the properties, the city ordered another valuation. The council accepted a lower appraisal of $290,000. One couple received $500 — about $5,000 in today’s dollars — for a quarter-acre parcel.

The Johnsons held out so long that the city boosted its original offer for the 15 acres — $35,250 — to almost $53,000. Still, they had to surrender the land that they wanted to develop. Their hopes of creating a refuge for Black people from housing discrimination had been crushed.

Anthony Santoro was an outsider: an Illinois native and president of a college in Maine. When he became Christopher Newport’s fourth president, in 1987, he inherited what he called an “impossible situation.”

The city, Santoro said, had “made a mess of” acquiring property for the campus. “They tried to build a school by eradicating a community, but they were only able to eradicate part of it. And that exacerbated the problem.”

While Christopher Newport occupied the geographic center of the Shoe Lane area, more Black families had moved there in the quarter-century since the 1961 taking. They built homes around the campus perimeter, joining longtime residents like the Johnsons. After serving six years in the Army, James Johnson worked at automotive plants, while Barbara taught home economics in a school for the deaf and blind. They raised three children, two boys and one girl.

The school’s master site plan called for extending the campus boundary and swallowing 90 more properties, including the rest of the Shoe Lane homes. Santoro dismissed using eminent domain: “It would have just started a new war.” The school had also promised not to “initiate, nor actively seek” to buy property in the Shoe Lane area. Nevertheless, Santoro said, Christopher Newport contacted each homeowner. Some simply refused to sell. But if the issue was money, the school met their price. “We paid a premium, as we should have,” Santoro said.

Many homeowners felt differently. They learned about the site plan not from Christopher Newport but from the newspaper, heightening their fears of a 1960s rerun, according to court documents. They felt that the plan would decimate their community. Additionally, despite Christopher Newport’s disavowals, they worried that the school might eventually take their properties by eminent domain, and that this prospect would scare off other buyers. They formed an association, which hired Richmond civil rights lawyer Gerald Zerkin. “It just seemed like they were getting screwed by Christopher Newport,” Zerkin said in an interview.

In 1989, the association sued Christopher Newport’s board and president and the governor of Virginia in federal court, seeking to block the expansion. Lawrence Brown, a resident who worked on the Apollo project for NASA, served as lead plaintiff. Katie Luck, who had moved to Shoe Lane in 1985 to care for an elderly friend, was among the homeowners who, through a public records request, gained access to Christopher Newport’s expansion plans. School officials contended that the site plan was merely “advisory” and an “internal working document.”

Judge Robert Doumar ordered the plaintiffs to include all affected Shoe Lane homeowners in the lawsuit. Otherwise, if some of them wanted to sell to the school, a ruling for the plaintiffs would interfere with legitimate transactions, he said. Saying it would be costly and time-consuming to track down all the homeowners and gain their permission, the association refused to comply with the order. Shortly before the trial was supposed to start, Doumar dismissed the lawsuit.

James Johnson was disappointed but not surprised. “We didn’t expect it to be in our favor,” he said. “We were against the whole city and the state.”

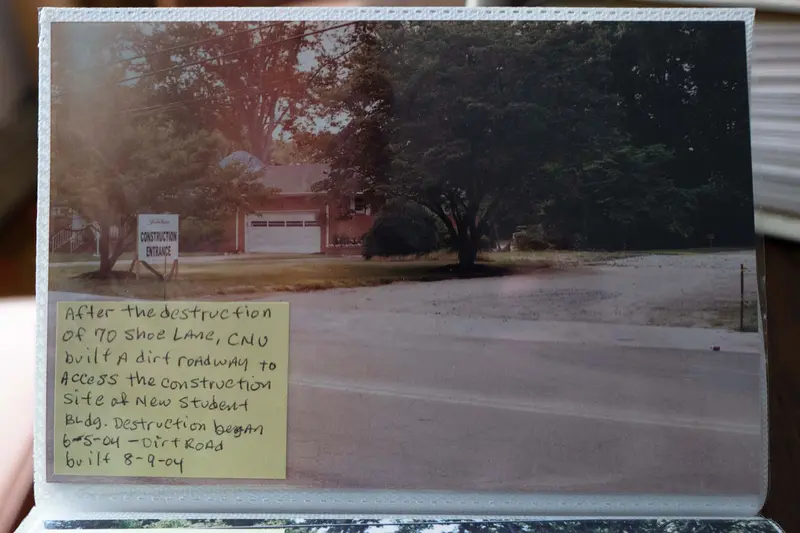

The defeat spurred James to photograph houses within the school’s site plan, knowing they might soon be razed. “I realized that people will never know this community, how it was,” he said. “I became very depressed.”

Christopher Newport kept expanding. From 1987 to 2019, it acquired at least 70 properties in the Shoe Lane area, far more than the city had taken by eminent domain in the 1960s, according to an analysis of real estate records. In 2003, the university, state and city partnered to acquire the Baptist church where many of the families worshipped; it was demolished to widen Warwick Boulevard.

During that period, the Johnsons sold one property to the university. Shoe Lane was being rerouted, creating a new entrance to the campus, and Aunt Alice’s old house, which James and Barbara had inherited, lay squarely in the road’s path. Having no other choice, they visited President Trible to talk terms. It was a cordial conversation, but the Johnsons were dismayed to see a map of the Shoe Lane area on Trible’s office wall, and a list of residents. Their name was on it.

Trible, a former U.S. senator from Virginia who was president of Christopher Newport from 1996 to 2022, said in 2001 that the university would not need to acquire properties by eminent domain. “Time favors Christopher Newport University,” he told the Daily Press. “This university is going to be around for hundreds of years. We’re going to get that land eventually.”

In practice, the university wasn’t so patient. In 2005, its board of visitors authorized Trible to take three properties by eminent domain for a parking lot, after negotiations reached an impasse. Black people appeared to own two of the lots. The university sought court approval to take at least one parcel, records show. A university spokesperson said that Christopher Newport’s real estate foundation purchased the properties without resorting to eminent domain.

Doug Hornsby, chief executive of the real estate foundation, left his business card in a Black resident’s mailbox in 2010. He followed up with a letter asking the homeowner to have the house appraised at his expense.

“I need you to know that I am not interested in selling my home,” the resident responded. Hornsby declined comment.

The next year, Trible advised the homeowner in a letter to expect to be “enveloped by bulldozers, cars and students in the days ahead.” He added, “If you decide you wish to sell your property, my colleagues and I would be happy to discuss this with you.”

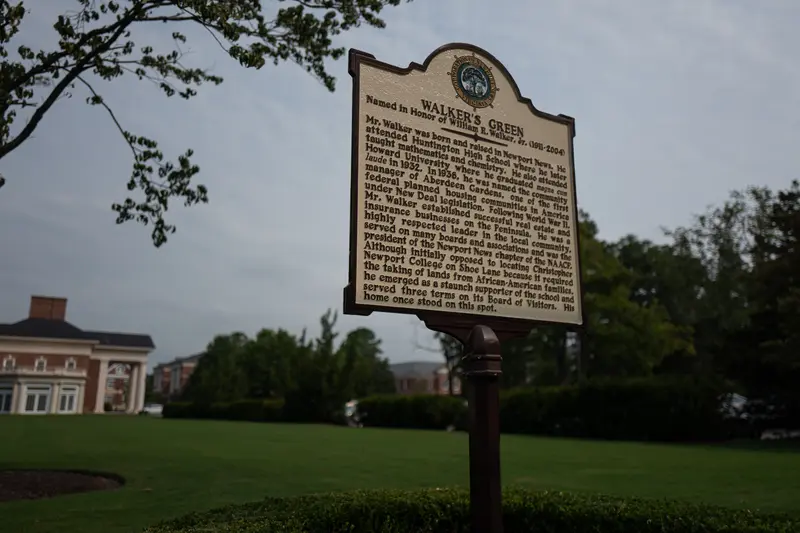

Between the homes of Luck and the Johnsons lies a three-quarter-acre patch of grass and trees owned by the university. It’s marked by a 2019 plaque that infuriates the Johnsons.

The plaque on the site of “Walker’s Green” honors their late neighbor William Walker. Walker was a real estate developer and president of the NAACP’s Newport News chapter. But he also served on Christopher Newport’s board while the school was expanding and the homeowners sued.

The plaque notes that Walker “initially opposed” locating the college on Shoe Lane in the 1960s “because it required the taking of lands from African-American families.” But what it omits is that during his time on the board, other homeowners were upset that Walker didn’t update them about the school’s intentions, and encouraged them to compromise. “He told us we should be happy we were in the master plan because we would always be assured” of a buyer for the homes, Luck recalled. The homeowners’ association terminated his membership. Rather than reflect this conflict, the plaque praises Walker for emerging “as a staunch supporter of the school.”

Hanchett, the Christopher Newport spokesperson, said that the park and the marker are “a tangible reflection of the University’s concern and respect for its neighbors past and present” and “honor the neighborhood’s residents who led the opposition.”

Former Christopher Newport president James C. Windsor, whom Hamilton interviewed for his book on the school’s history, advised him to leave out the debate over its location because it was too controversial, the historian said. Hamilton had been unfamiliar with the issue, but the ex-president’s comment piqued his interest, and he dug into the taking of Shoe Lane. Windsor died in 2016.

Like Christopher Newport, William & Mary hasn’t fully grappled with its role in Shoe Lane’s demise. Its official history states that the city donated the land, without mentioning how, and from whom, it was obtained. In 2009, William & Mary’s board did acknowledge that the college had failed to take a stand against segregation during the Jim Crow era. Nine years later, it apologized for perpetuating “the legacies of racial discrimination.”

Nationally, and in Virginia, the higher-education playbook has hardly changed. In the past two decades, universities in Miami, Phoenix, Philadelphia and more than a dozen other cities have developed research parks in former Black and Latino communities, often through eminent domain, said Davarian Baldwin, an American-studies professor at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut.

“We want to hold on to the belief in the idea that universities are a positive influence on communities around them,” Baldwin said. “But there's a whole area of consequences that we have rarely looked at until very recently.”

Some Black community leaders have called for reparations. Baldwin has worked with residents and elected officials in Connecticut, Pennsylvania and California to push for compensation and support for displaced communities. In 2021, the mayor of Athens, Georgia, apologized to the Linnentown families whose homes were demolished for the University of Georgia’s expansion.

In Newport News today, the mayor and all but one city councilor are Black. The James River Country Club admitted its first Black member in 1990. “I worked very hard to get the club to change its policies,” Santoro said. It “has everybody in it now.” Although Newport News is more than 40% Black, just 7% of Christopher Newport’s students are Black.

Save for the plaque to Walker and another on the former site of the Baptist church, the once-prosperous Black community on Shoe Lane has almost vanished. In a cemetery just down the road from the university, the headstones marking where residents and church parishioners are buried are worn with time, some barely legible.

Despite the schoolboy’s taunt, Luck is staying put. “I’m not selling to the college,” she said. “I don’t know what my children might do. But I’m not selling.”

The Johnsons say they aren’t bitter toward Christopher Newport. Two of their children graduated from the university. But they say they feel like strangers on land where they should belong. They don’t know how much longer they will stay in their home, or if the decision will be up to them — or their children, who would inherit under their will. The university’s updated site plan calls for acquiring the last houses in the neighborhood by 2030.

Barbara Johnson is often asked why she and her husband chose to live in the middle of a college campus. “They didn’t know we were here before the college,” she said.

“This is where we have our roots. We built this ourselves. When you put your sweat and blood into something, you don’t give it up.”

Gabriel Sandoval, of ProPublica, contributed research.

Some reporting for this story was supported by a fellowship from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.

Reach Brandi Kellam at [email protected] or [email protected] and Louis Hansen at [email protected].

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Gabriel Sandoval, of ProPublica, contributed research.

Some reporting for this story was supported by a fellowship from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.

Reach Brandi Kellam at [email protected] or [email protected] and Louis Hansen at [email protected].

Gabriel Sandoval, of ProPublica, contributed research.

Some reporting for this story was supported by a fellowship from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.

Reach Brandi Kellam at [email protected] or [email protected] and Louis Hansen at [email protected].