EPA Report Finds That Formaldehyde Presents an “Unreasonable Risk” to Public Health

Oil executive Tom Ragsdale walked away from his old wells, making the pollution left behind the state of New Mexico’s problem. His tactics, however, are ubiquitous in the industry.

A long-awaited report from the Environmental Protection Agency has found that formaldehyde presents an unreasonable risk to human health. But the report, released Thursday, downplayed the threat the chemical poses to people living near industrial plants that release large quantities of the carcinogen into the air.

The health risk assessment was published weeks after a ProPublica investigation found that formaldehyde, one of the most widely used chemicals in commerce, causes more cases of cancer than any other chemical in the air and triggers asthma, miscarriages and fertility problems.

Our analysis of the EPA’s own data showed that in every census block in the U.S., the risk of getting cancer from a lifetime of exposure to formaldehyde in outdoor air is higher than the goal the agency has set for air pollutants. The risk is even greater indoors, where formaldehyde leaks from furniture and other products long after they enter our homes.

In its report, the EPA evaluated 63 situations in which consumers and workers encounter formaldehyde and found that 58 of them contribute to the chemical’s unreasonable risk to health — a designation that requires the agency to mitigate it. Among the products that can emit dangerous levels of formaldehyde in these scenarios, according to the report, are automotive-care products like car waxes, along with crafting supplies, ink and toner, photographic supplies and fabrics, building materials, textiles and leather goods.

While a note accompanying the EPA’s report stated that workers have the greatest exposure to the chemical, the agency’s risk assessment adopted weaker standards for protecting workers from formaldehyde than had been proposed in a previous draft. The move was decried by some environmentalists, including one who said it would affect hundreds of thousands of people whose jobs require them to come into contact with the chemical.

By law, the EPA should now begin the next stage of regulation: drafting restrictions to mitigate the risks it identified. But even before the agency released the report, House Republicans urged the administration to invalidate it. And a chemical industry group immediately attacked the report as flawed, accusing the EPA of “pursuing unaccountable lame duck actions that threaten the U.S. economy and key sectors that support health, safety and national security.”

Good journalism makes a difference:

Our nonprofit, independent newsroom has one job: to hold the powerful to account. Here’s how our investigations are spurring real world change:

Texas lawmakers pushed for new exceptions to the state’s strict abortion ban after we reported on the deaths of pregnant women whose miscarriages went untreated.

The Supreme Court created its first-ever code of conduct after we reported that justices repeatedly failed to disclose gifts and travel from the ultrawealthy.

The Idaho Legislature approved $2 billion for school repairs after we revealed just how poor the conditions were in the state’s crumbling schools.

The EPA proposed a ban on the toxic pesticide acephate after we highlighted the agency’s controversial finding that the bug killer doesn’t harm the developing brains of children.

Support ProPublica’s investigative reporting today.

We’re trying something new. Was it helpful?

How — and whether — to rein in the risks of formaldehyde promises to be one of the first tests of the EPA under a second Trump administration. The relatively inexpensive chemical is ubiquitous, used for everything from preserving dead bodies to making plastics and semiconductors. On the campaign trail, President-elect Donald Trump repeatedly said he supports clean air. But he has also vowed to roll back regulations he views as anti-business — and industry has rallied around formaldehyde for decades.

When Trump first assumed office in 2017, the agency was preparing to publish a report on the toxicity of the chemical. But one of his EPA appointees, who was given a high-ranking role in the agency’s Office of Research and Development, was a chemical engineer who had worked to fend off the regulation of formaldehyde as an employee of Koch Industries, whose subsidiary made formaldehyde and many products that emit it. The report was not released until August 2024, long after Trump’s appointee left the agency.

According to ProPublica’s analysis of the EPA’s 2020 AirToxScreen data, some 320 million people live in areas of the U.S. where the lifetime cancer risk from outdoor exposure to formaldehyde is 10 times higher than the agency’s ideal. ProPublica released a lookup tool that allows anyone in the country to understand their outdoor risk from formaldehyde.

Still, the EPA decided in its finalized assessment that those health risks are not unreasonable, echoing a draft the agency released in March. Back then, to determine whether formaldehyde posed an unreasonable risk of harm, the EPA compared levels in outdoor air to the highest concentrations measured by monitors in a six-year period. The ProPublica investigation found that the measurement the draft report used as a reference point was a fluke and had not met the quality control standards of the local air monitoring body that registered it.

That explanation was absent from the final version released this week. Instead, it offered several new rationales, including that some formaldehyde degrades in the air and that levels vary over people’s lifetimes, but it came to the same conclusion as the draft had: that formaldehyde in outdoor air isn’t a threat that needs to be addressed.

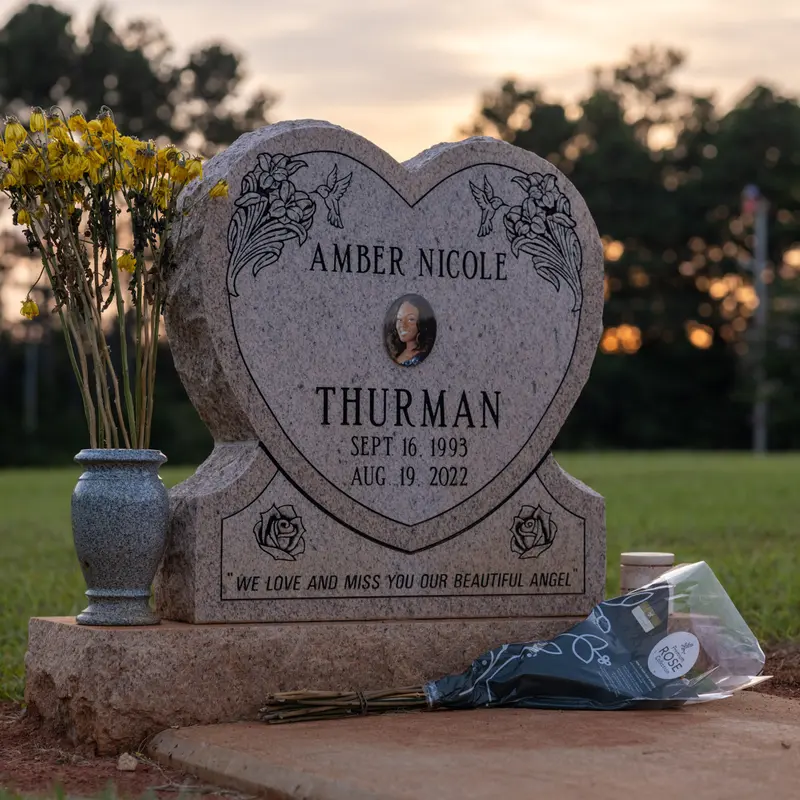

That decision leaves people living near industrial plants — known as fence line areas — with little hope of protection, according to Katherine O’Brien, a senior attorney at Earthjustice, who has closely followed the EPA’s efforts to regulate formaldehyde.

“Despite calculating very high cancer risks for people in their homes and also fence line community residents, EPA has completely written off those risks, and set the stage for no regulation to address those risks,” said O’Brien. “That’s deeply disappointing and very hard to comprehend.”

Compared to the draft published in March, which was heavily criticized by industry, the final version contained weaker standards for protecting workers. The acceptable levels of workplace formaldehyde exposure set in the final version of the assessment were significantly higher than the levels in the earlier draft of the report.

Maria Doa, senior director of chemicals policy at the Environmental Defense Fund, expressed alarm over the decision. “This is a less protective standard that would leave workers at risk,” said Doa, a chemist who worked at the EPA for 30 years. She noted that the report’s figures show an estimated 450,000 workers could be left vulnerable to the effects of formaldehyde as a result.

The EPA press office did not immediately respond to questions about its determination for outdoor air or the change it made to the value set to protect workers.

It’s unclear what parts, if any, of the new report will be allowed to stand.

Last month, Rep. Pete Sessions, R-Texas, urged the incoming administration to make revisiting the Biden EPA’s work on formaldehyde “a top priority for 2025.” In a letter to Lee Zeldin, Trump’s pick to run the agency, Sessions derided this week’s report as “based upon unscientific data that was utilized by unaccountable officials at the EPA to tie the hands of the new Administration and hamper economic growth.” (The letter was first reported by InsideEPA.)

Sessions, who is a co-chair of the new Delivering Outstanding Government Efficiency caucus and a staunch ally of Trump, recommended scrapping the EPA’s assessments of formaldehyde and reversing course on “broader Biden policies” on chemicals.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.