Eugene Clemons May Be Ineligible for the Death Penalty. A Rigid Clinton-Era Law Could Force Him to Be Executed Anyway.

His lawyers presented no defense at trial. Then a clerk’s office misplaced a plea for his civil rights behind a file cabinet. Now, it’s almost impossible for the federal courts to address the problems with his case.

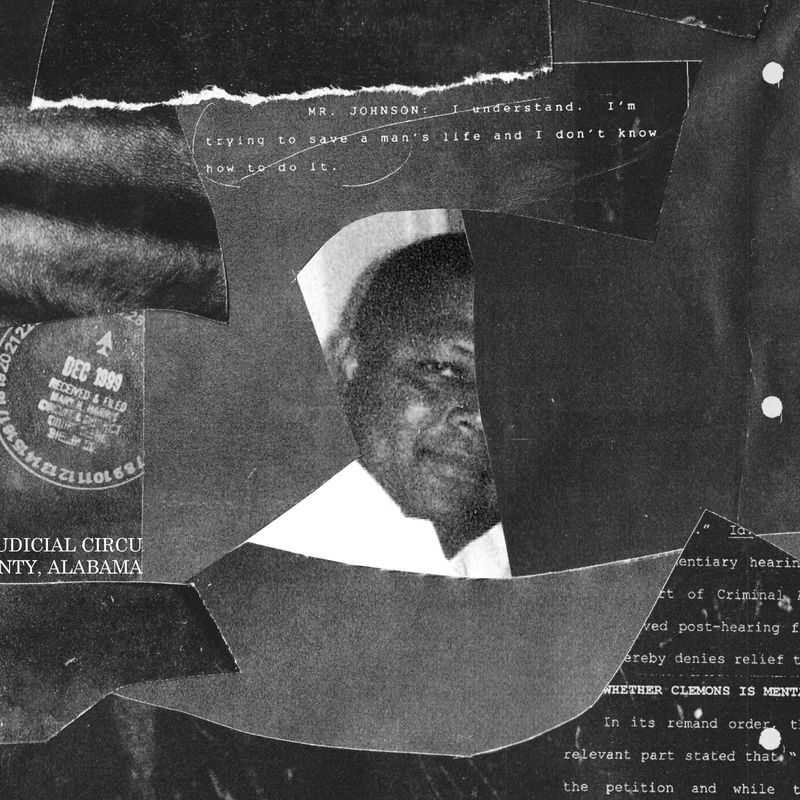

In the spring of 2000, James S. Christie Jr. left his law firm in Birmingham, Alabama, for a short drive to the Shelby County Clerk’s office. He was going to clear up some confusion, a seemingly small technical error that had been bothering him for months. The clerk’s office kept claiming that it had no record of a document Christie said he had filed at the end of the previous December. That document, and its timing, were exceedingly important. It alleged, among other things, that the trial attorneys for a man on death row had defended him so badly, neglecting to call even a single witness to convince the jury to vote against execution, that the man’s right to a fair trial had been compromised.

Christie knew Shelby County should have had proof of the document’s existence. A few months earlier, on December 27, 1999, Christie’s courier had delivered the filing to the clerk’s office and been handed back a copy, stamped at the top in red and blue with the words “received & filed,” along with the date and the clerk’s name. Christie had that copy of the document right there in his hand.

The 41-page petition contained critical information — claims no court had yet considered — about a man named Eugene Clemons. It described how his lawyers, when it came time to argue that his life should be spared for killing a Drug Enforcement Administration agent, completely ignored the long history of abuse Clemons had suffered. They’d also failed to point out that Clemons had well-documented mental disabilities: As a first grader, he was described by school officials as “educably mentally retarded.” If jurors had been made aware of Clemons’ history, of the life he had lived before he was arrested at age 20, perhaps they would have voted against his death sentence.

Christie and his colleagues had been careful to file the document a month in advance of a crucial federal deadline that had been imposed several years earlier by a controversial criminal justice law. They hoped and expected that the filing would allow Clemons’ appeal to leave Alabama courts and enter federal court, for what’s called a habeas corpus hearing. Habeas corpus, which in Latin means “you have the body” (and translates, colloquially, to “in the flesh”), can provide a vital final check against unlawful or arbitrary punishment.

The concept, which dates back hundreds of years and was established in U.S. law in 1789, intends to protect the incarcerated by guaranteeing that they can formally contest, in person and before the proper authorities, potentially unjust imprisonment. For state prisoners, the so-called “Great Writ” has, in egregious cases, been a mechanism to appeal for reason from a federal court. The lawyers in Clemons’ case hoped a federal judge would grant him a new trial, one during which jurors would hear about Clemons’ life and his many struggles, before deciding whether he should die. It was a long shot, but it wasn\'t impossible.

Now, standing inside the Shelby County courthouse, Christie showed a clerk’s office employee his stamped copy of the filing. She acknowledged that the document in his hand was real, but still, the office staff could find no record of the original. Christie set about trying to find it.

He would later recall that a woman in a small side office pointed him toward a filing cabinet that was pushed against a far wall. On top sat a rectangular filing tray, where the employee told Christie she would throw pleadings before later depositing them in the filing cabinet. Christie could see that behind the tray there was a gap between the cabinet and the wall. He began tilting the cabinet to one side and then the other until it was far enough from the wall that he could peer behind it. Sitting on the floor were three court filings. One of them was Eugene Clemons’ missing document.

Christie drove back to Birmingham. The confusion, he thought, had been cleared up.

It hadn’t.

Though the state of Alabama later acknowledged that the filing was “misplaced and was never docketed,” the Alabama Attorney General said that the court should not honor the original stamped date because Christie never paid a $140 filing fee. Christie and his assistant at his law firm said that he had called ahead and that a clerk’s office employee had told him no filing fee would be needed. That made sense to Christie, because Clemons had been deemed too poor to afford an attorney in his criminal trial. (The clerk, Mary H. Harris, told ProPublica that she could not recall the incident: “I don’t even remember what you\'re talking about.”)

But under Alabama law, for the fee to be waived Christie was supposed to file a form along with the petition, confirming that Clemons couldn\'t afford the $140. Because the document had been lost, nobody in the county clerk’s office was able to ask Christie to correct the error by paying the fee or filing the form. Christie later filed an amended petition with the form, but it was too late. By refusing to certify the earlier filing on the date the clerk had initially stamped it, the state of Alabama was ensuring Clemons would never get his claims heard by a federal court.

Twenty-one years later, Clemons’ long appeals process is reaching its end: A final petition for federal review is now sitting with the U.S. Supreme Court. The Justices could decide as soon as June 3 whether to hear his argument. Christie has not had any active role in the case for at least a decade, yet he said he’s been unable to forget the lost petition and the unpaid fee: “I have got a lot of this on my mind from years ago.” Christie, who in 2018 ran unsuccessfully for attorney general of Alabama as a Democrat, has never before spoken openly about his misgivings surrounding the Clemons case. The confusion at the county clerk’s office, he said, “may result in someone losing their life.”

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office would not reply to questions about the case and instead sent a copy of its reply to Clemons’ petition. The state has asked the Supreme Court not to accept the case, arguing, among other things, that missing the filing deadline made it ineligible for the court\'s review

“The circuit clerk and her employees were not responsible” for making sure that Clemons’ petition was properly filed, the Alabama Attorney General’s filing said. “That was his counsel’s responsibility, and it was only because of their negligence that his petition was not properly filed.”

The misplaced document, whether Christie’s fault or the clerk’s or both, would not have caused any trouble before April 1996. A rigid one-year deadline for filing federal habeas petitions was imposed that year by the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. The law, a frenzied anti-crime response to the Oklahoma City bombing the previous year, is widely considered to contain the most significant curtailment of habeas rights in 150 years.

President Bill Clinton explained in a statement that accompanied the law the day it was signed that it was meant “to streamline federal appeals for convicted criminals sentenced to the death penalty,” even as it preserved the “independent review of federal legal claims.” In many ways, it has done neither. Death penalty habeas claims still take decades to reach an end. And for people in prisons across the country, AEDPA has imposed impassable obstacles to getting a hearing in federal court: not just shorter, more restrictive deadlines but impediments at nearly every stage of the appeals process. With few exceptions, federal courts could no longer intervene to correct alleged miscarriages of justice in state convictions. Rather than fix a broken system, the law put the Great Writ in a straitjacket.

“As a result of AEDPA, federal courts can no longer care about enforcing federal rights,” said Eve Brensike Primus, a law professor at the University of Michigan. “We’ve lost sight of the actual underlying questions, which are: ‘Were your rights violated?’ ‘Did you have a fair trial?’”

The legislation passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, one in a series of law-and-order reforms in the zero-tolerance era. Then-Senator Joe Biden had championed the most sweeping of those laws, the 1994 Crime Bill. But two years later, he had reservations about AEDPA’s threats to habeas. Biden tried to introduce an amendment to remove the one-year deadline that would later plague Clemons. He argued that the bill should not strip fundamental rights from people in state prison systems. He failed to push the amendment through and, joining 90 of his colleagues, voted for AEDPA anyway. Dozens of people under death sentences and, experts say, thousands of other state prisoners have missed the one-year deadline since the law passed in 1996.

In addition to imposing the deadline, AEDPA has made it more difficult for federal judges to reverse questionable decisions of state courts. In the last decade, the Supreme Court has repeatedly interpreted AEDPA to limit the kinds of cases federal judges can reconsider to those that exhibit “extreme malfunction,” a standard that remains murkily defined. Ultimately, even when federal judges believe that state courts are wrong, there’s very little they can do about it. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which includes Alabama, has been particularly inflexible in its interpretation of AEDPA.

There are some judges and prosecutors who have found AEDPA to be a necessary measure to stop federal courts from “rehashing old battles that should have already been resolved,” according to Joseph Colquitt, who served as an Alabama circuit court judge for 20 years until the early 1990s, when he began teaching law at the University of Alabama. In the period leading up to the passage of AEDPA, Colquitt said, “federal habeas was basically a ticket into court at any time, any place, any reason.”

Colquitt said that the interminable cycle of habeas petitions “was defeating the process of punishment.” AEDPA, he said, was a clear attempt to streamline the habeas process.

AEDPA’s supporters in Congress expected the legislation would “end the charade of endless habeas proceedings,” as the chair of the House Judiciary Committee, Rep. Henry Hyde, said in the lead-up to the bill’s passage. Lawmakers of both parties agreed that habeas appeals should move more quickly. Those who supported the law had done so with the presumption that state courts would, in general, ensure fairness, and that federal courts could still intervene when those state courts drew “unreasonable” conclusions.

But that is not the legal order AEDPA has built. Instead, as one federal judge, a Reagan appointee, wrote in 2015, “We now regularly have to stand by in impotent silence.” In 2020, referring to Clemons’ case, a judge on the 11th Circuit likened the legal threshold for winning a federal habeas appeal to “crossing the ocean into the abyss of unreasonableness.”

The impact of the law has outpaced even the dire predictions of AEDPA’s most strident opponents. In the 22 years prior to the law’s passage, 40% of death row defendants who had habeas petitions heard by federal courts succeeded in getting their verdict or their sentence overturned, according to data compiled by the legal scholars David Dow and Eric Freedman. From 2000 to 2006, AEDPA had reduced that rate to about 10%. More recent data has not been compiled, but habeas and death penalty scholars say it’s only become harder to get a federal court to consider death penalty appeals. This, they say, almost certainly means that people whose death sentences would have been overturned are still on death row, or have been executed, as a result of AEDPA.

Clemons is 49 years old and has spent the last 25 years in Alabama’s Holman Prison. His lawyers are now requesting that the Supreme Court reckon with whether Clemons, as a person with intellectual disabilities, should be protected from the death penalty. And they have asked the Supreme Court to step past the late filing and consider Clemons’ allegation that his legal defense in Alabama was, as one habeas scholar called it, “effectively nonexistent.”

On September 25, 1994, before an all-white jury, Shelby County District Attorney Robby Owens described the killing of a man named George Douglas Althouse, “an all-American guy.” Late one night two years earlier, Althouse, a 28-year-old DEA agent from Pennsylvania working undercover in Alabama, was sitting in the passenger seat of a Camaro Z/28 parked at a Chevron station, while the car’s driver, a sheriff’s deputy who was Althouse’s roommate, was inside looking up a phone number. A man got in the Camaro, pulled a gun, and made clear his intention to steal the car. As Althouse reached for his own gun, the thief shot him, twice. Althouse pushed himself out of the car and kneeled on the concrete, firing several shots as the assailant took off in the Camaro. When his colleague rushed outside, he found Althouse lying on the ground, bleeding profusely.

Eugene Clemons, who was 20 at the time, was arrested just over a week later in Cleveland, Ohio, where he’d grown up and where he’d traveled immediately after the shooting. Because Althouse was a federal agent, Clemons, along with another man who’d been involved in the heist, initially were prosecuted by federal authorities. In federal court, Clemons was promptly convicted; his lawyers had raised a failed alibi defense. He was sentenced to life in federal prison, where there is no possibility of parole. The federal death penalty did not apply to the crime at the time.

Days after Clemons was found guilty in federal court, Alabama was ready with charges of its own. The state wanted more than life in prison. “If ever there’s a case for the death penalty, this is it,” Owens, the district attorney, told the jury. “Mr. Doug Althouse never did anything in this world except try to make it a better place to live. It’s an honor for me to represent him here.”

Since Clemons had already been sentenced to life in prison, his attorneys’ primary objective was to keep their client alive. Mickey Johnson, an experienced Alabama attorney then in his mid-40s, was one of the two attorneys appointed by Judge D. Al Crowson to Clemons’ case. He addressed the judge before the trial began.

“Your Honor, I know this type of interruption is highly irregular,” Johnson said, speaking to the judge out of earshot of the jury, “but in all honesty, I’m fixing to stand up and give an argument, and I’m not even sure yet what my defense is. I’m trying to save a man’s life and I don’t know how to do it.” Johnson’s difficulty, he later explained, was that Clemons was now claiming he was innocent, but Johnson was certain an innocence defense would not work; Clemons’ attorneys representing him in the federal case had already tried that and failed.

Sitting beside Johnson was his law partner, Rodger Bass, a young attorney who had been admitted to the Alabama bar just nine months before.

Clemons didn’t testify in his own defense, but during the trial, the transcript shows, he was becoming distraught. “These folks are trying to kill me, man,” Clemons said in open court to the judge. “I fire these lawyers.” Crowson told Clemons to stop talking. Clemons continued to protest, and then addressed Douglas Althouse’s mother, who was sitting in the courtroom: “I’m sorry y’all got to go back through this, Mrs. Althouse.”

“I\'m going to go ahead and bound and gag you,” Crowson said, and then sent Clemons to a holding cell.

After the prosecution spent four days making its case, Johnson and Bass did not call any witnesses. Rather, they told the jury in their closing argument that there was no evidence that Clemons had intended to murder Althouse before the car heist and that they should convict him not of capital murder but felony murder, which is not eligible for a death sentence.

“Let me tell the attorneys I appreciate the splendid job they\'ve done on representing their respective sides of this cause,” Crowson said after closing arguments.

The jury found Clemons guilty of capital murder.

Clemons’ hope now rested on the sentencing stage of the trial: The jury would decide whether Clemons would be sentenced (again) to life in prison, this time at the state level, or would be executed.

The state called just one witness: Arlene Althouse, the victim’s mother. She catalogued her loss. “The hardest thing I think for me is not to be able to pick up the phone and call him,” she said. “I miss his hugs, his laughter. You could never stay mad at him, because he always ... he always had a way of making you laugh.”

It was now the defense team’s opportunity to present mitigating evidence, to humanize Clemons in an attempt to spare his life. During sentencing proceedings, defense attorneys typically call on their clients’ relatives, teachers or friends, or others who can help shed light on factors that might have contributed to the defendants’ actions. It is a time to describe mental illness or trauma, childhood abuse or mental disability. Many people who knew Clemons were able to provide such testimony. He had a history of all of those things.

“Any witnesses for the defendant?” Crowson asked.

“No,” Johnson replied.

When Johnson stood to give closing arguments in the sentencing phase of the trial, he didn’t have much to offer: “I honestly don’t really know what to say. I don’t have anything prepared to say. I just don’t know how to do it.”

Before the jury sentenced Clemons to die, Johnson made one final statement.

“I guess the fact that I don’t have anyone sitting over here to come up here and talk to you about what Eugene Clemons was like as a kid or anything else, maybe it’s not even important to anybody, maybe there is not anybody that it’s that important to that they are willing to come up here,” he said. “I really don’t know.”

There were, in fact, more than a few people willing to testify on behalf of Eugene Clemons. Standing outside the courtroom for most of the trial were Clemons’ mother, aunts and cousins. The women had been placed under subpoena, not by Clemons’ defense attorneys but by the state. Yet they were never called by either side.

Nearly three decades after the trial, in May 2021, Johnson told ProPublica that rather than call Clemons’ family into court, he had decided he would instead try to appeal to the jury’s conscience by claiming that Clemons’ family had abandoned him at this crucial time.

He said he’d found the family “very unpleasant,” that “they had their own ideas of how to defend him,” and that he did not think any of Clemons’ relatives “would make a compelling witness about his life.”

In a deposition conducted by Clemons’ pro bono appellate lawyers in 2001, Johnson explained that he’d tried the day before the sentencing hearing to reach Clemons’ grandmother, who’d been his legal guardian as a teenager in Alabama, to ask her to testify. But Johnson had not been able to get her on the phone. He said he had not tried again, nor had he asked the judge to postpone the hearing. Johnson admitted then, and again in 2021, that he made no effort to find others to testify.

How, he wondered in 2021, could he have engendered compassion for a man whose “whole lifestyle was, I don’t know, for lack of a better word, gangster type.” Clemons had already been in trouble by the time he was arrested for murder. He’d served 11 months in Alabama prison for a previous armed car robbery. He got out on March 6, 1992, and according to testimony in the murder trials, played a key role in three more armed carjackings before he shot and killed Althouse. All of that presented what Johnson called “an insurmountable hurdle” to build compassion with the jury.

He wound up telling the jury, “In my own mind there is some redeeming social value in the fact that ... his history of crime that we heard about didn’t leave a trail of dead bodies.”

Kim Samuels, one of the relatives who stood outside the courtroom in 1994, is now 57 years old. She lives in a large brick house on a quiet, manicured cul-de-sac in Chesapeake, Virginia. She and her husband Guillermo settled down to raise their children there after years of moving around the world following Guillermo’s naval deployments. In all that time, Samuels, who has built a career as a business consultant, has been exceedingly quiet about the fear she feels most days, wondering “when they will execute Gene.”

Two generations of Samuels’ family have been born knowing only indirectly of Gene, her baby cousin, for whom she had served as babysitter and guide. Samuels was 31 years old, nearly half a life ago, when she traveled to meet her aunts in hopes of sitting in on the Alabama trial to provide some moral support to her cousin. But they had not been allowed into the courtroom.

During the trial, Judge Crowson had heard knocking on the courthouse door. He told the jury to leave, then ordered the door to be opened. Four women walked in. One, who identified herself as Clemons’ aunt, told Crowson that this was “a mock trial.” Crowson threatened to send the women to the county jail if they did not remain outside.

In her Chesapeake home, Samuels laid a pile of decades-old photographs on the dining room table. Samuels’ nine-year-old granddaughter, who spends days at the house attending her remote school classes, asked about one fading image: “Is that him as a kid? Is that his father?” The photo had been taken in Cleveland at Samuels’ grandparents\' house, where Samuels had helped teach Gene and the other younger cousins to ride bikes, Kool & The Gang blaring on the radio. In the photo, Gene sits on a bench, squeezed between his parents, wearing a red sweater and a collared white shirt. His mother, in a knee-length dress, smiles at the camera. His father, Eugene Clemons Sr., stares blankly vacant to the side.

“That’s how he always looked,” Samuels remembered of Clemons’ father. “He was a messed-up guy.”

Samuels cannot recall a time before the abuse. She said that as far back as she can remember, Clemons’ father beat and tormented his son, inflicting bruises and fear. (Through a relative, Clemons’ father declined to speak with ProPublica; his mother died in the late 1990s.) Samuels remembered sitting with Eugene’s mother in the living room and begging her aunt to leave her husband. But, Samuels said, Clemons’ mother felt trapped; she depended on her husband’s income to get by.

Clemons’ sister, Raquel Scott, younger than him by four years, said in a recent interview, “Our father was abusive towards my brother and my mother.” She said she could not bear to speak of the details. Others have recounted some of them. There is the story that Clemons’ paternal grandmother, Katherine Clemons, shared during an appeal in state court in 2001, also held before Judge Crowson. She testified that years earlier, she had visited her son’s house outside of Cleveland and heard a noise coming from inside the diaper pail. “I forced myself to take the lid off, because I knew something was in there,” she said. When she opened the pail, she found baby Gene, no older than two, stuck inside, soaking wet from diapers. Her son had closed him in the pail to punish him.

“Eugene was slow,” Samuels said, a description Scott confirmed. He was six when his school administered tests to figure out why he was struggling to learn and assigned him to special education. Samuels remembered that when their grandparents would take all of the children to church, Clemons could not repeat short passages of scripture that younger kids could rattle off with ease. The other children, at school and at church, would harass him for his slow, slurred speech.

Scott isn’t sure if it was the abuse, brain damage or an intellectual disability from birth that was the reason her brother “did not thrive.” When Clemons was a teenager, he moved with his grandparents to a split-level home in Bessemer, Alabama. His mother had granted her own parents custody of her son. The last time Samuels saw Clemons before he was first arrested, she spent a week visiting her grandparents before she departed for a job overseas as a software developer. “I told him to be careful who you spend time with,” she recalled. Clemons was failing high school and eventually, after repeating the 10th grade, dropped out.

A little over a year after Samuels’ visit, Clemons was arrested for murder.

Samuels said that she would certainly have shared what she knew about her cousin with the jury: “If they’d ever asked us, we would have told them everything. We’d have told them.” In her testimony before the appeals court years later, Katherine Clemons said she too had wanted to travel to Alabama for the trial, and would gladly have offered her observations about her grandchild to the jury, if only she\'d been asked. “I really wanted to come,” she said. “I definitely would have been there.” In an interview, Scott said the same: “I would do anything to help my brother.”

Twenty-seven years after Clemons’ trial, Mickey Johnson said he believed he should have done more to try to protect his client. When asked if he had provided Clemons with adequate representation at the sentencing stage, Johnson, who still practices law outside of Birmingham, said, “Probably not.”

Johnson said, “In today\'s world, yes, I think that would be viewed as absolute ineffective assistance.”

Back in 1994, Johnson said, defense attorneys didn’t always mount the same intensive effort to humanize their clients as they would today. But the Supreme Court, in a series of cases in the 2000s, said that attorneys had been obligated at least as far back as the 1980s to conduct thorough investigations into their death penalty clients’ history, in order to present a defense that could build empathy with the jury.

Six years after Clemons’ trial, Johnson and his partner, Bass, were appointed by Judge Crowson to defend a man named Alan Eugene Miller, who was charged with triple murder. The same prosecutor who’d tried Clemons, District Attorney Robby Owens, also tried that case. Again, Johnson opted against calling anyone from his client’s family, or anyone else who knew him. And before the trial, Johnson told The Birmingham News that, much like in his earlier defense of Clemons, he was struggling with his legal strategy: “How do you defend somebody who shot three people and left eyewitnesses who knew who they were looking at? I wish you’d tell me.” At trial, Johnson told jurors, “I think Mr. Owens pretty much got it right.” Miller was convicted of murder.

But this time, the jury was split on the question of death. Alabama was then one of a few states to allow judges to impose the death sentence when one or two jurors dissent; it is now the only remaining one. Crowson obliged the majority of the jurors, even as he called his decision “the most difficult sentence that I’ve ever had to consider.” It was one of at least three cases in which Crowson handed down a death sentence following a split jury.

The work of representing people on death row is not easy. And attorneys appointed to take those cases in Alabama at the time of the Clemons case were paid a pittance. In the mid-1990s, the state had set a cap on how much court-appointed defense attorneys could be paid: $40 an hour for court time and $20 an hour for out-of-court work, rates that were common among Southern states. That meant that many attorneys refused to do capital work. Johnson put in a bill for $6,625 for the Clemons case, an amount he acknowledged did not begin to cover his time. Bass billed for $7,101. (Bass died in 2002.)

When asked whether he thought he should have accepted clients he did not believe he could defend, Johnson said he didn’t think he had much of a choice: The judge had appointed him to the cases, and refusing might risk upsetting a judge whose goodwill he would need to depend on for other cases.

After Clemons was sentenced to die, Judge Crowson appointed an attorney, William Felix Mathews, to handle an appeal before the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals. Mathews, like Johnson, also admitted that he should have done more for Clemons. In a 2001 deposition conducted by the pro bono lawyers who later represented Clemons, Mathews said he “was very stressed out” and overworked while conducting Clemons’ appeal. He was having marital problems. He was losing focus. He was mixing antidepressants with alcohol, which affected his ability to practice law. He said he’d done little to investigate Clemons’ background or hire an investigator to do it for him.

“Do you believe you were a zealous advocate?” one of Clemons’ lawyers asked Mathews during the deposition. “No,” he said. Three years after he handled Clemons’ appeal, Mathews was disbarred for reasons unrelated to the Clemons case. Mathews could not be reached for comment.

Alabama only provides lawyers to death penalty defendants at trial and for their first appeal. It is the only state that does not pay for lawyers to handle the next appeal. In 2001, the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit legal advocacy group, filed a lawsuit to try to force Alabama to pay. Clemons was one of the plaintiffs. They lost.

To fill the gap, nonprofit organizations and well-resourced law firms have stepped in with pro bono support. That’s how John Christie entered the case, as local counsel for a large international law firm called Winston & Strawn. The firm estimates that between 1999 and today, its attorneys have committed the equivalent of $6.3 million worth of pro bono time to defending Clemons during the appeals process. But because of AEDPA and the missed filing deadline, that massive investment has not been enough to overcome the mistake of failing to pay a $140 fee.

In June 2002, a decade after Clemons was arrested for murder and two and a half years after Christie’s courier delivered the doomed filing to the Shelby County clerk, a ray of hope emerged in the form of a Supreme Court decision.

“In the light of our ‘evolving standards of decency,’” the court wrote in the decision, Atkins v. Virginia, states cannot execute people with intellectual disabilities. The decision applied retroactively. Since Atkins, at least 136 people have been removed from death row on account of their intellectual disabilities.

Even though AEDPA’s rigid deadline had excluded Clemons’ claims, including those about ineffective trial defense, the Atkins decision meant that his lawyers could challenge his death sentence on new grounds. If they could show that he fit the clinical standards for intellectual disability, Alabama would not be allowed to kill him.

First, Clemons’ lawyers would have to make the argument before Judge Crowson. In 2004, Crowson held a lengthy evidentiary hearing on Clemons’ mental capabilities.

At the time, clinical standards for diagnosing intellectual disability required evidence of three things: an IQ below 70 or, accounting for the margin of error, 75; proof of struggles with “adaptive functioning,” how well a person can handle common demands in life; and evidence of both in childhood. Clemons as a first grader had been diagnosed by his school as “educably mentally retarded,” and his school records were replete with teacher notes about his impairments, his slowness, his “great difficulty” to learn. He’d been held back twice, still got failing grades, and eventually dropped out. Since then, he’d undergone a series of IQ tests that, his lawyers said, put him just within the range to be considered disabled. When combined with evidence that Clemons had struggled to function in everyday life during the few years he lived as an adult before his arrest — his supervisor at a Domino’s Pizza, for instance, told the court that Clemons “was just unable to do the job despite all his efforts” — Clemons, his lawyers argued, was exactly the kind of person the Supreme Court had been seeking to protect with its Atkins decision.

The attorney for the state argued that Clemons had been faking his impairment during some of his IQ tests. And in a filing to the court, the state said that Clemons’ IQ was too high for him to be eligible for Atkins relief. The state then pointed to all the ways that Clemons had been able to function, suggesting that his inability to keep a job derived from laziness, not disability, and that his ability to board a bus when he left Alabama for Ohio after the murder belied the possibility of disability.

After the hearings, as is often the case, Judge Crowson asked both sides to draft proposed orders and send them to him, to elaborate on their positions. A month later, in October 2004, Crowson returned his order. “This Court finds that Clemons is not mentally retarded,” it said.

Clemons’ attorneys were not surprised: Alabama courts almost never reverse death sentences. But what struck them was that Crowson’s order was a near exact copy of the proposed order that the Alabama Attorney General’s office had sent him. The final order even contains the Attorney General’s original typos, including misspelling Eugene as “EUGUNE,” in all caps. The judge made a few cosmetic changes here and there, but the decision otherwise appeared to be the work of the Alabama attorney general.

In a recent phone interview, Judge Crowson, who retired in 2005, said that the order he signed reflected his opinion: “I heard both sides argue, and then I adopted it.” The state’s order, he said, “was the same I was thinking, and I based it on the law.” Crowson declined to comment further on the Clemons case.

Clemons’ team was ready to appeal the judge’s ruling to federal court — and this time there was no AEDPA deadline standing in their way.

The habeas petition Clemons’ attorneys filed on his behalf argued that Judge Crowson’s order did not take into account their claims and that it was a mere rubber stamp of the state’s proposed order: “As one might expect from an order drafted by the Attorney General, the substance of the order is shockingly biased,” the lawyers wrote in a brief. Crowson’s order cites five IQ tests in which Clemons scored between 51 and 84. (The highest score was from a short test that experts said is not a reliable measure of intelligence.) The order downplays the lowest of the scores and states that Clemons had been faking impairment every time he scored below 70. And even though the attorney general’s office had said at the outset that it would follow the three-pronged clinical analysis for intellectual disability, the order fails to mention evidence about one of those prongs: Clemons’ adaptive deficits.

To Clemons’ legal team, the problems with the order seemed to be just the kind of shortcomings that a federal court would want to review. But they were about to learn the extent to which AEDPA had crippled the ability for a higher court to intervene.

AEDPA requires that federal courts mostly defer to the decisions of state courts, rather than review any legal arguments anew. The language of the law does allow federal judges to wade back into a case, but only under the strictest circumstances: when they can prove that a state court’s decision was “unreasonable.” And the Supreme Court has repeatedly narrowed what “unreasonable” means.

As a result, the prosecutors’ version of the story can become gospel. A federal public defender in Alabama, where verbatim adoption of prosecutors’ orders is common, described what happens after orders are signed by judges as a recurring nightmare for the defense: “It keeps coming back and coming back.” In Clemons’ case, the order that Crowson adopted had advanced through three courts by the beginning of 2020.

In July 2020, Clemons’ attorney, Eric Bloom, then with Winston & Strawn, was finally able to argue the case before a three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit. “This court is not bound to defer to unreasonably found facts or to the legal conclusions that flow from them,” he said.

The judges seemed receptive to what Bloom was saying: that they were not looking at the judge’s own words but, rather, were being asked to accept a document prepared by one side.

“It’s really hard to understand how the court took all of these scores into consideration,” Judge Charles R. Wilson said during oral arguments, referring to Clemons’ IQ tests, “when it adopted the state’s proposed order verbatim, including typographical errors and misspellings.”

Wilson pressed Alabama’s solicitor general, Edmund G. LaCour Jr., to explain the exclusion of the evidence regarding Clemons’ adaptive deficits from the order that Judge Crowson signed. “None of this is in the decision though, right?” Judge Wilson asked.

“No, your honor,” LaCour said, acknowledging the omissions. “But, this is AEDPA.”

“For purposes of AEDPA review,” LaCour countered, “The federal courts are not in the business of checking the state’s homework.”

It was not the first time an 11th Circuit judge had bristled at having to adhere to AEDPA’s strict deference requirement when confronted with an order they knew a judge had not written. In the case of a defendant named Doyle Hamm, an Alabama judge in 1999 had signed an exact copy of the Attorney General’s 89-page proposed order — one business day after the state delivered it to him. He had not so much as removed the word “proposed” from the top.

“I don’t believe for a second that that judge went through 89 pages in a day and then filed that as his own,” said 11th Circuit Judge Adalberto Jordan. Even so, Jordan joined his colleagues in deferring to that order. “I know what AEDPA deference requires me to do,” he said.

The judges knew what they had to do in Clemons’ case, too. In July 2020, the 11th Circuit issued its decision: “Because Clemons filed his federal habeas petition after April 24, 1996, this case is governed by AEDPA,” Judge Stanley Marcus wrote, citing the date the law was signed. The court denied Clemons’ habeas petition.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court justices will hold a conference to decide which cases they will take up in their next term. Eugene Clemons’ habeas petition is among the 145 cases up for consideration that day. The justices are likely to take only a handful of them. Nearly three decades after he was arrested for the murder of Douglas Althouse, this is the last stop in Clemons’ habeas fight.

“The various wrongs converge in a shocking way,” Clemons’ petition reads. His lawyers’ position, laid out in the document, is simple: Clemons is intellectually disabled and should not be executed, and the errors with the 1999 filing should not have prevented him from making the case before a federal judge that his trial counsel failed him.

The petition was accompanied by four amicus briefs, statements of support from experts or organizations. One, from the National Association of Social Workers, claims that beyond any clinical doubt Clemons is a person with intellectual disabilities. “The state court’s failure to adhere to the clinical standards ... was egregious,” the brief said. “That the sentencing jury never heard any evidence of Mr. Clemons’s cognitive impairment ... renders the case tragic.”

A libertarian group called the R Street Institute filed an amicus brief describing the “Kafkaesque series of misstatements and missteps by court officials” in Shelby County, which “led Mr. Clemons’ counsel to believe that Mr. Clemons’ petition had been properly and timely filed.”

Habeas and death penalty experts say Clemons’ case is a prime example of the type of lower-court missteps that the federal courts should be able to remedy. “This is a clear injustice,” said John Blume, a leading habeas scholar and law professor at Cornell University, who coauthored another amicus brief in the case. “Because of a series of mistakes, he got no review on anything but his intellectual disability claim, which was just adopted by the state judge without inspection.”

Last year, in response to the 11th Circuit decision rejecting Clemons’ petition, Marshall, the current Alabama attorney general, said in a statement: “For 28 years, Clemons has evaded his just fate. I applaud yesterday’s decision by the 11th Circuit, which moves us a step closer to ensuring that justice will be done for Special Agent Althouse and those he left behind.”

In its reply to Clemons’ Supreme Court petition, Alabama said that 31 of the 32 claims in his habeas petition are moot because of that late filing fee: “His counsel’s failure to properly file [the petition] before AEDPA’s limitations period expired was the result of their negligence.” Regarding the 32nd claim, about intellectual disability, it says that even if Clemons would be considered disabled by today’s standards — the Supreme Court in the years since Atkins has imposed a unified standard — Alabama courts had been free all those years before to determine themselves how to evaluate disability.

No amicus briefs were filed in support of Alabama\'s position.

Several habeas and death penalty experts said in recent interviews that it is exceedingly unlikely that the Supreme Court will agree to hear Clemons’ case. The court in recent decades has moved only to fortify AEDPA’s barriers, not to loosen them, fashioning the law into something even more restrictive than even Congress had intended.

Opponents of AEDPA say that any possible reform — and any restoration of habeas rights — likely will have to start in Congress.

Biden has said that he will back legislation to end the federal death penalty and press states to follow. (Many states, including Alabama, are extremely unlikely to do so.) But as president, he has said nothing about AEDPA, nor has any member of Congress floated any legislation to change it.

“Congress has written a statute that keeps courts from doing what they are supposed to do,” said Eric Freedman, a leading habeas scholar at Hofstra University’s law school. “They could reform it.”

“The right to habeas corpus is critical to rectifying injustices and government misconduct,” said former Senator Russ Feingold, who at the time of the law’s passage was one of just eight senators to vote against it. “I feared that AEDPA would do what it has, which is to limit access to the courts for people on death row.”

Freedman and Feingold also suggest lifting the one-year deadline, so that prisoners can’t be denied relief over a mistake.

For Eugene Clemons, congressional action, of which there are currently only rumblings, may mean little. Alabama could proceed to schedule an execution date at any time if his petition is rejected by the Supreme Court. In the spring, the last time Clemons called his cousin, Kim Samuels, he asked her why she thought he had been sentenced to death. They rarely talked about the question. Samuels’ response was to read him scripture over the phone. “Gene,” she told me, months later, “he never even had a chance.”

Mollie Simon contributed reporting.