A Dubious Arrest, a Compromised Prosecutor, a Tainted Plea: How One Murder Case Exposes a Broken System

One innocent man’s odyssey through the justice system shows the cascading, and enduring, effects of a bad conviction.

The case of Demetrius Smith reads like a preposterous legal thriller: dubious arrests, two lying prostitutes, prosecutorial fouls and a judge who backpedaled out of a deal.

It also delivers a primer on why defendants often agree to virtually inescapable plea deals for crimes they didn’t commit.

ProPublica has spent the past year exploring wrongful convictions and the tools prosecutors use to avoid admitting mistakes, including an arcane deal known as an Alford plea that allows defendants to maintain their innocence while still pleading guilty. Earlier this year, we examined a dozen such cases in Baltimore.

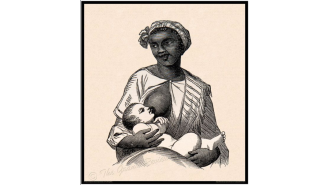

Smith’s troubling ordeal, Alford plea included, is a road map of nearly every way the justice system breaks down — and how easily a cascade of bad outcomes can be triggered by one small miscarriage of justice. For Smith, a young black man in Baltimore, it started with a questionable collar. Nine years later he’s still struggling to clear his name.

Smith’s saga began in the summer of 2008 in the low-income, high-crime neighborhood in southwest Baltimore where he lived. A man named Robert Long had been shot twice in the head execution-style that March. Long was a cooperating witness in a police investigation, and the killing had all the makings of a hit.

A man and a female prostitute both claimed to have seen the murder and fingered Smith. At the time, Smith was 25 and had a record of minor drug and assault offenses. When he was arrested about three months after the murder, Smith was adamant that he had nothing to do with it.

At this point, the justice system appeared to work as it should. Smith had a bail hearing before a judge who said the prosecution’s evidence was nothing more than “skeletal allegations.” In a rare move for a murder case, Baltimore District Judge Nathan Braverman released Smith on $350,000 bond.

“It was probably the thinnest case I’d ever seen,” Braverman, now retired, said recently. Smith’s alleged crimes were the most heinous of the cases before him that day, he said, but Smith was the only one granted bail — a sign of how weak the evidence was.

But what should have been the first step in freeing Smith from a misguided murder charge instead further ensnared him. Braverman’s bail decision drew sharp public criticism, and Smith was soon back in the sights of the same detective who investigated the murder.

About a month later, Detective Charles Bealefeld arrested Smith again, this time for allegedly shooting a man in the leg during a late-night robbery. Bealefeld, the brother of the then-police commissioner, wrote in his report that “word on the street” was that Smith was the assailant.

Smith lived near the victim and told police he knew the victim’s parents well enough to call them by nicknames. But the victim never named Smith or described his assailant as someone he’d seen before. He said only that a black male in his 20s shot him. Later that night at the hospital, the victim identified Smith from a photo array. Bealefeld then found a second witness, another prostitute, who he said also picked Smith out of an array.

At this point, Smith was convinced Bealefeld was targeting him. He told his lawyers that the detective had admitted during the arrest that he knew Smith didn’t do it. Bealefeld left the Baltimore police in 2008 amid a federal investigation into a racial incident in the department in which he was named publicly by a city councilman and local media. He declined to comment. Bealefeld is now an officer with the Annapolis Police Department.

After Smith’s second arrest, the head of the police union told the local press that it proved Braverman had been reckless in releasing Smith. “It’s frustrating to police officers who did the hard work to get this guy charged,” the union head said, calling for the judge to be banned from presiding over bail hearings.

Smith was jailed until his murder trial 18 months later, and unwaveringly maintained his innocence. The cases against him were remarkably similar: The prosecution relied almost exclusively on eyewitness testimony — and in each case a key witness was a prostitute.

In January 2010, Smith went on trial for Long’s murder. Prosecutor Rich Gibson, a six-year veteran of the Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s Office, hung his case on the testimony of the man who’d first identified Smith as the killer. The witness claimed he’d not only seen the murder from a nearby pay phone, but knew why it was done. Long, he said, had stolen drugs from Smith. Gibson ran with that theory, building Smith’s history of minor offenses into a story of a neighborhood kingpin slaughtering the victim to send a message about what happens to those who steal from him.

What Gibson didn’t tell the jury was that the witness was an informant for the police whose assistance on multiple cases had repeatedly kept him out of trouble. The witness only told police he’d seen the murder after he was arrested on an unrelated charge, according to police files. And, court records show, the witness had a clear understanding that any breaks he got for his testimony would best be hidden from the defense. At one point, he even wrote the judge in his case directly to ask for a sentence modification for his participation in Smith’s murder trial, saying “as you already know, the detective nor the state’s attorney can contact me about my matter because that would be promising me something for my testimony.”

Even more troubling, there was evidence that the witness wasn’t at the scene of the murder at all. Baltimore has cameras panning much of the city 24 hours a day, and the murder was caught on tape. The shooter couldn’t be seen, but what was clear is that no one was at the pay phone at the time of the shooting, said Michele Nethercott, the head of the Innocence Project Clinic at the University of Baltimore Law School. The prostitute who also said she witnessed the murder wasn’t on the video either, Nethercott said. It’s unclear why the video footage wasn’t addressed in detail at Smith’s trial. Gibson declined to comment about his actions in the case.

The jury found Smith guilty. When he was sentenced to life plus 18 years, Smith told the judge, “They know I didn’t do this.”

That conviction did more than send Smith to prison. It pushed him into choices he never would have made.

A year after his murder trial in February 2011, Gibson offered Smith a plea deal on the still pending charges for the shooting. Smith, proclaiming his innocence, reluctantly agreed. The system had failed him so badly once, he felt like he was “in a no-win situation,” Smith told the court.

The deal Smith made is known an as Alford plea. It allows a defendant to say for the record that he’s innocent of the crime but believes the state has enough evidence to convict him. Still, Smith railed against a central piece of Gibson’s evidence — that the victim had identified Smith from a photo array. That didn’t make any sense, Smith told the judge, since the victim “was my neighbor. He didn’t say ‘my neighbor did it.’ He didn’t say, ‘Well that guy across the street did it.’”

Under the plea, Smith would serve 10 years concurrently with his life sentence. But Smith was worried about what would happen when he was exonerated, which Smith fervently believed would happen eventually. If he was no longer serving a life sentence, he didn’t want to be stuck serving the 10 years for another crime he didn’t commit. So, he wanted his plea deal to have an escape hatch: He must be allowed the chance to get out of the 10-year sentence if he was found innocent of the murder.

Baltimore Circuit Judge Barry Williams called the deal “strange,” but agreed that under those circumstances Smith could come back to his courtroom to revisit the plea. Gibson also agreed, according to a transcript, and that unlike most plea deals he would allow Williams full discretion.

The agreement was also laid out the next day by Smith’s public defender in a court filing. It said that although Williams made no promises about what his ruling would be, the judge would nevertheless be the one to “determine whether to change the sentence” and “the assistant state’s attorney agreed not to oppose the judge’s ruling.”

“I’m copping out to something I didn’t do,” Smith said at the hearing. “I just want to get it over with.”

Astonishingly, mere months later in the spring of 2011, Smith’s stubborn faith seemed validated.

During a related investigation, the U.S. attorney’s office in Maryland had turned up Long’s real killer and informed Baltimore prosecutors that they had the wrong man. Federal agents quickly unraveled the case against Smith. It wasn’t about drugs, as Gibson had argued. Instead, the victim, Long, had been killed in a murder-for-hire plot to keep him from testifying about crimes committed by his boss. Long had also specifically warned the Baltimore authorities not to include his lawyer in a meeting about cooperating because the lawyer worked for his boss. But they did it anyway. Six days after police searched his boss’ home based on Long’s information, Long was dead.

At Smith’s murder trial, however, Detective Steve Hohman had testified that there was no reason to investigate Long’s boss. He left out that police had done several interviews with Long’s associates that pointed to the boss as a suspect, Long’s family had told them that the boss threatened to kill Long days before his death, and the police had requested the boss’ phone records. But that information wasn’t turned over to Smith’s defense, a violation of Smith’s constitutional rights. Gibson told the jury that “no stone was left unturned.”

Federal agents also discovered that the prostitute who’d identified Smith had been six miles away receiving methadone treatment around the time of the murder. She recanted her statement, telling federal investigators that Hohman had yelled, banged the table and generally pressured her into her testimony. (By this time, the state’s other key witness, who supposedly saw Smith from a pay phone, was dead.)

Hohman has since been promoted, and the Baltimore Police Department said it stands by its investigation.

Gibson and the state’s attorney’s office continued to insist to Smith’s lawyers that Smith had been justly prosecuted, according to Smith’s public defender and Nethercott, the innocence lawyer who later took up Smith’s case.

A year and a half went by while Smith remained locked up, serving a life sentence for a murder someone else had committed. Under pressure from federal prosecutors, the state finally and quietly dropped the case against Smith in August 2012.

“What was driving this case really was the U.S. attorney,” Nethercott said recently. The federal government was about to indict and prosecute another person “while Demetrius was sitting there serving life on a theory that was completely different.”

Rod Rosenstein, the top federal prosecutor in Maryland at the time and now the deputy attorney general of the United States, announced that the federal case had “resulted in the exoneration of an innocent man and the conviction of the real killer.”

No such declaration came from Baltimore prosecutors.

“What they were not willing to do,” Nethercott said, “was to say: ‘We clearly made a mistake.’”

Their error didn’t just damage Smith. Braverman, the judge who’d scoffed at the prosecution’s case, had been shortlisted to move up to the circuit court at the time of the bail hearing, according to The Baltimore Sun, but he wasn’t selected. After Smith’s case, the local press closely covered Braverman’s subsequent bail decisions. There was no follow-up acknowledgement from the police or others that his instincts had been right about Smith.

And even though Smith was cleared of Long’s murder, he was still in maximum security prison in Hagerstown, Maryland, serving his 10-year sentence for the robbery shooting.

In May 2013, as promised, Smith went back before the judge to revisit the terms of that deal. By this time, he’d been in prison for nearly five years.

The case was now being handled by Tony Gioia, then head of the state’s attorney’s conviction integrity unit. Gioia made no mention of Smith’s innocence on the murder charge, telling the judge that the prosecution had “moved to vacate the murder conviction for a Brady violation” by the original prosecutor, Gibson. Brady refers to the 1963 Supreme Court ruling that said prosecutors must turn over evidence of innocence to the defense for a trial to be fair.

Gioia said he’d reviewed the police documents about the shooting, and had “some issues about the facts.” He agreed to modify Smith’s sentence to time served and release him immediately on three years’ probation. Smith was free.

But on paper he was still a convicted felon for the shooting, limiting his ability to get a lease and a job — he had three offers revoked after a background check. Smith wanted a clean record and to be completely free of the system that had now eaten up nearly a decade of his life.

In the four years since his release, damning new evidence had emerged that echoed the murder case. The prostitute recanted her statement implicating Smith and said she’d been coerced into identifying Smith by Bealefeld, the detective who investigated both of Smith’s cases.

The night of the shooting, the prostitute had told police she heard gunshots and saw a man she’d been with earlier flee the scene. Bealefeld, she said, showed her an array of photos and repeatedly pointed to a picture of Smith, saying “That’s him, isn’t it?” When she continually denied that Smith was the man she saw, Bealefeld threatened to arrest her.

“I was afraid I’d be locked up, and so I finally signed the array as he had directed me,” she said in an affidavit in June 2013.

But the new evidence had come too late. Maryland gives defendants a special path to challenge their conviction with new evidence of innocence, but those who take plea deals are barred. Smith’s Alford plea meant he couldn’t get the conviction vacated.

He had one last option: Ask Judge Williams to modify his plea deal again.

With the help of new pro bono lawyers, Smith filed a motion to change his sentence for the shooting from “time-served” to “probation before judgement,” which means a judge withholds finding a defendant guilty so long as the defendant successfully completes a period of probation. Since Smith had finished his three years of probation, the change would essentially wipe the conviction off his record.

On July 28, Smith walked back into Williams’ courtroom in a light blue blazer with hope that the judge would finally end his ordeal.

When Smith’s case was called, a familiar face stood up for the prosecution. Gibson, the original prosecutor, was back and he told the judge he opposed any changes.

“What’s your basis for saying ‘no’?” Williams asked him. “You acknowledge” that on the murder charge “he was exonerated; is that correct?”

“The State acknowledges,” Gibson responded, “that — that after the case was tried, and the defendant was convicted of murder, and after the — the Court of Appeals affirmed that conviction, my office, after discussions with federal authorities, chose to vacate that conviction to allow the federal prosecution to go forward the way they envisioned it.”

Williams looked taken aback. “So, you’re stating in open court that your office isn’t saying that he wasn’t guilty. You just did it for other reasons?”

Gibson offered only a vague reply, and Williams kept pressing him, at one point interjecting with exasperation that “it’s a simple question.”

In all, Gibson evaded the question five times before Williams abruptly stopped and ruled that Smith’s original guilty plea was a binding plea — meaning that the only way it could be changed was with the support of the prosecutor.

That contradicted how both the judge and the prosecutor had defined the plea six and a half years earlier. At the time in 2011, Gibson said that the terms of the deal meant Smith could “come back and put it before the judge and the judge can do whatever he’s going to do with it.”

And Williams had specifically noted the plea meant that the prosecution was “giving up the right to say to this court, ‘Judge, you cannot change it.’ He now has acknowledged that. ... It will be up to me to make a decision.”

But now, for reasons he didn’t explain, Williams said, “I have not the authority ... despite what I would, what I may or may not want to do it’s irrelevant.”

“Motion is denied.”

Smith’s lawyer, Adam Braskich, jumped up to argue that was incorrect, but the judge cut him off with a curt “thank you.”

In the hallway outside the court, Smith shook his head, not entirely surprised. His gold teeth flashed through a smile. “It is what it is,” he said. “You keep fighting.”

Braskich and Smith’s other lawyer, Barry Pollack, thought it was clear the judge had the legal authority to change Smith’s sentence.

“After being wrongfully convicted of murder and then convicted for an assault he didn’t commit, Demetrius served five years in prison,” Pollack said. “He should not also be saddled with a felony conviction. We didn’t think a fresh start was too much to ask, and we’re disappointed that Demetrius still can’t put this behind him.”

Williams declined to comment on his ruling.

The next possible step is to apply for a rare pardon from the governor.

Like Gibson — who’s running for state’s attorney one jurisdiction over in Howard County, Maryland — the current Baltimore City state’s attorney, Marilyn Mosby, won’t say whether her office believes Smith is innocent of the murder, or the shooting. Spokeswoman Melba Sanders provided a short, written statement that said the office couldn’t comment on the review process that led the prior administration to vacate Smith’s murder conviction, but “we respect their decision.”

If any case should cause prosecutors to concede mistakes, Nethercott said, it’s Smith’s. “What’s so striking about Demetrius’ case is there are very few times when you come in with an innocence claim that’s supported, endorsed and proven by the Unites States government,” she said. “If that doesn’t move people, it’s hard to see what would.”