4,000-year-old Egyptian skull may have evidence of ancient cancer treatment.

Another great discovery.

The ancient civilization of Egypt has always been renowned for their advancements in medicine, and a recent discovery has only added to their impressive reputation. Archaeologists have uncovered a 4,000-year-old skull that shows signs of possible brain surgery, making it an extraordinary find. Upon further examination, scientists have determined that the cutmarks on the skull could be evidence of an ancient attempt to treat cancer.

As experts continue to study the skull, they have proposed two possible theories for the cutmarks. One possibility is that the ancient Egyptians were trying to operate on the excessive tissue growth caused by cancer. However, another theory suggests that they may have been trying to learn more about cancerous disorders after the patient's death. This new evidence aligns with what we already know about ancient Egyptian medicine - they were exceptionally skilled at identifying, describing, and treating diseases and injuries, even going so far as to put in dental fillings.

Despite their advanced medical knowledge, there were still some conditions that the ancient Egyptians could not treat, including cancer. However, this recent discovery suggests that they may have attempted to do so. A team of international researchers closely examined two human skulls, both dating back thousands of years. Lead author Prof Edgard Camarós of the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain expressed his excitement over the findings, stating that this is a unique piece of evidence that sheds light on how ancient Egyptian medicine approached cancer more than 4,000 years ago. He believes that this discovery is a game-changer in our understanding of the history of medicine.

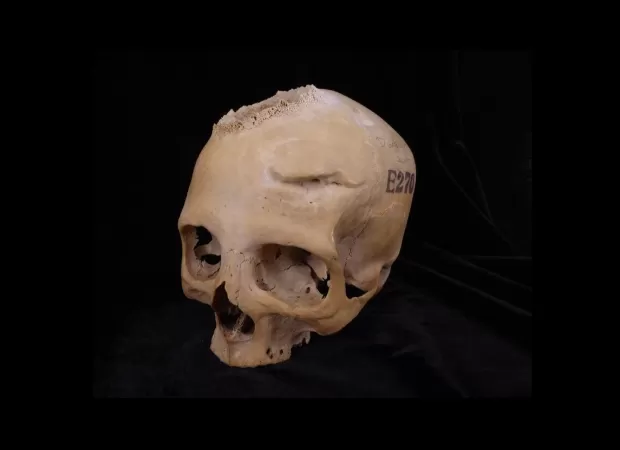

The two skulls in question, known as skull and mandible 236 and skull E270, are currently held at the University of Cambridge's Duckworth Collection. The first skull belonged to a man aged 30 to 35, dating back to between 2687 and 2345 BC. The second skull belonged to a woman older than 50, with a dating of between 663 and 343 BC. According to the study's first author, Dr Tatiana Tondini of the University of Tübingen in Germany, this finding is significant because it shows that despite the ancient Egyptians' advanced medical knowledge, cancer was still a medical frontier for them.

The team's research has also revealed that the ancient Egyptians had a wide range of medical practices, including surgery and the use of medicines derived from plants and animal products. They even had instruments that were similar to what we use today, such as scalpels, forceps, scissors, and splints. Further microscopic observation showed a large lesion on skull 236, consistent with excessive tissue destruction, also known as neoplasm. The skull also had around 30 small and round metastasised lesions, which were surprising to the researchers. Even more astonishing were the cutmarks found around the lesions, possibly made with a metal instrument.

Co-author Prof Albert Isidro, a surgical oncologist at the University Hospital Sagrat Cor in Spain, believes that this discovery shows that the ancient Egyptians were not only skilled at treating diseases but also conducting experimental treatments and medical explorations related to cancer. The team also found a cancerous tumour on skull E270, which had led to bone destruction. This finding suggests that cancer may have been a common disease in the past, and not just a result of modern lifestyles and environmental factors.

Aside from evidence of cancer, the research team also found two healed lesions from traumatic injuries on skull E270, one of which seemed to have come from a violent event using a sharp weapon. This finding raises questions about the role of women in ancient Egyptian society and their involvement in conflicts and warfare. Dr Tondini wonders if the woman was involved in any warfare activities, questioning our previous assumptions about women's roles in ancient times.

Studying skeletal remains comes with its own set of challenges, making it difficult to make definitive statements, especially when there is no known clinical history. However, the researchers are hopeful that this discovery will pave the way for future research on the field of paleo-oncology. They believe that more studies will be needed to fully understand how ancient societies dealt with cancer and other diseases. The study, published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, marks a significant step forward in understanding the history of medicine and the capabilities of ancient civilizations.